Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 9: Understanding Linux Operating System Basics

9.2 History and Benefits of Linux

9.3 Linux Architecture

9.4 Linux File System Overview

9.5 Basic File System Navigation and Management Commands

9.6 File Properties and Permissions

9.7 Editing File Properties

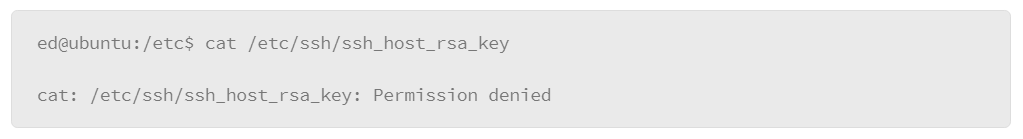

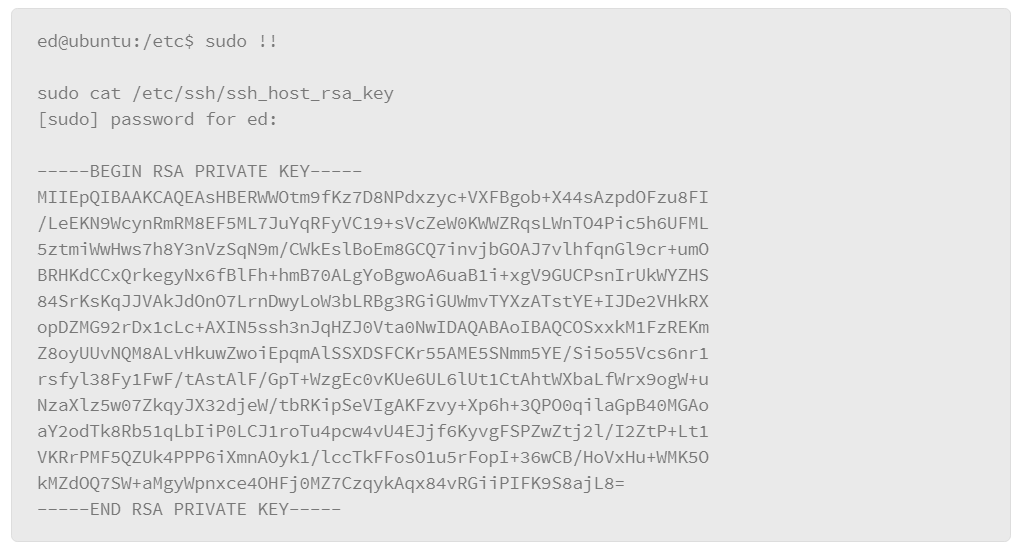

9.8 Root and Sudo

9.9 Disks and File Systems

9.10 System Initialization

9.11 Emergency/Alternate Startup Options

9.12 Shutting Down the System

9.13 System Processes

9.14 Interacting with Linux

9.15 Linux Command Shell Concepts

9.16 Piping Command Output

9.17 Other Useful Command Line Tools

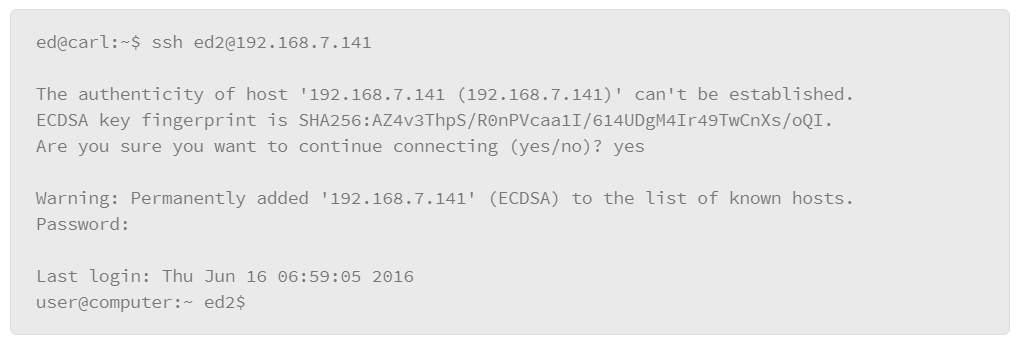

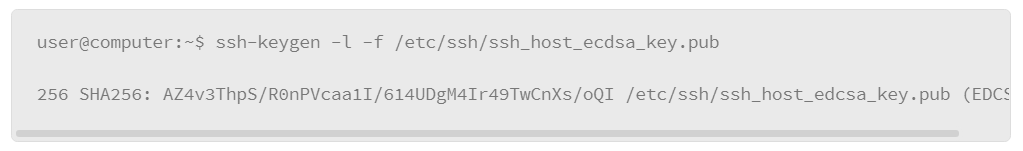

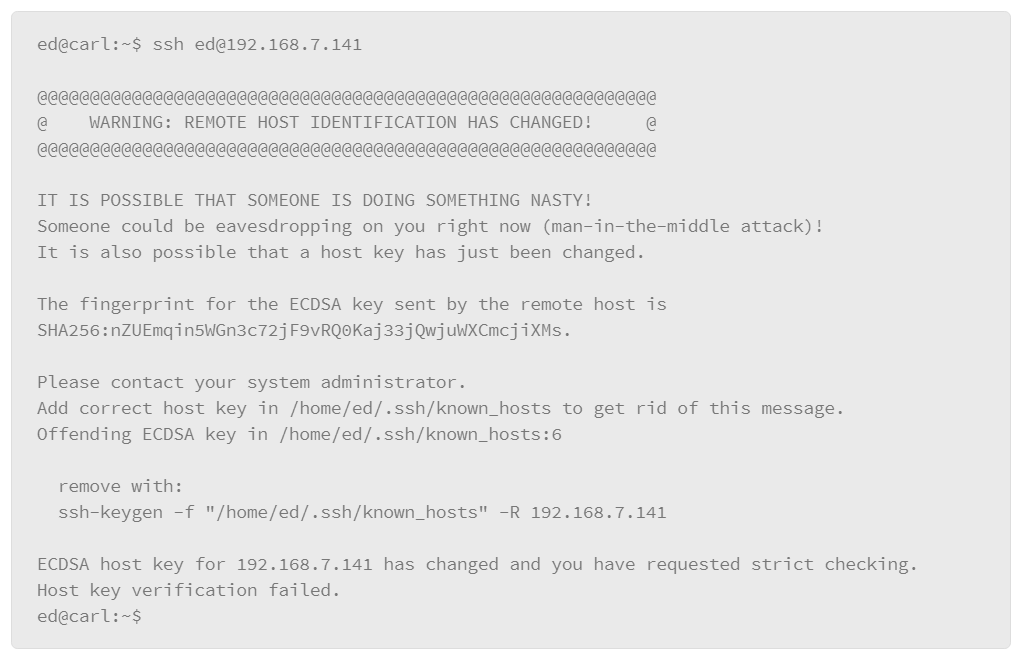

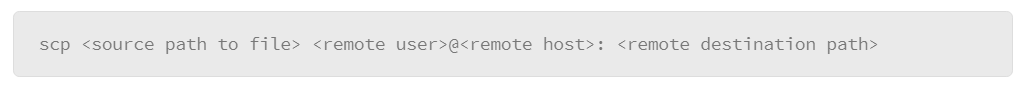

9.18 Overview of Secure Shell Protocol

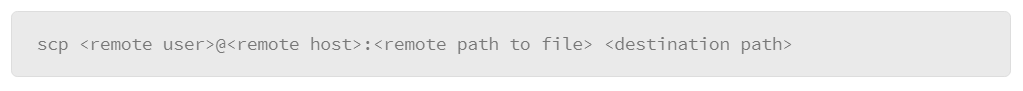

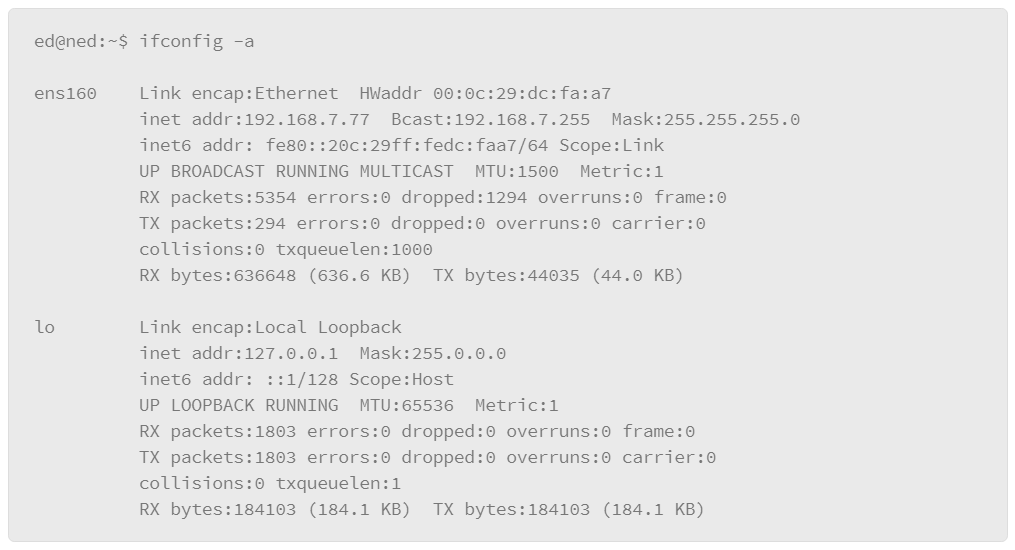

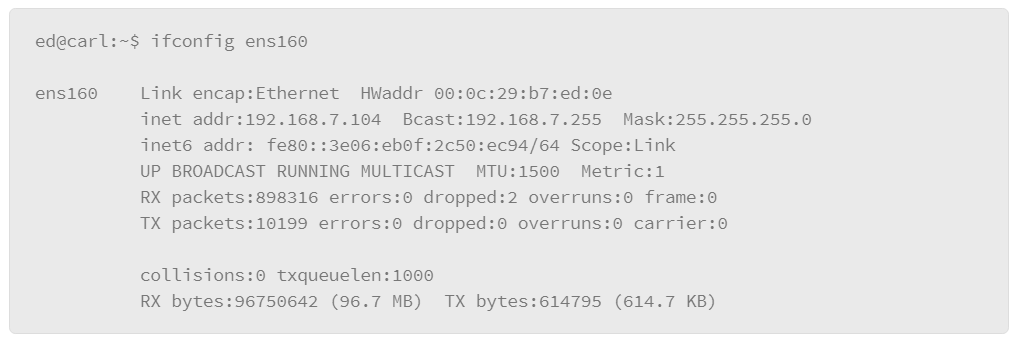

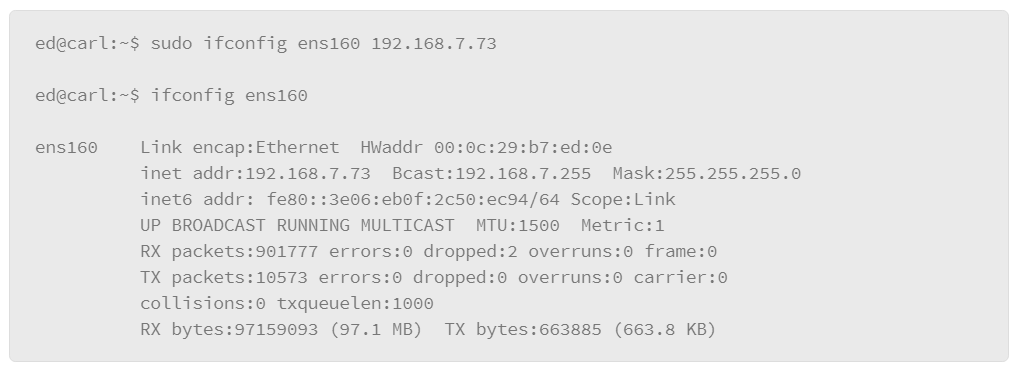

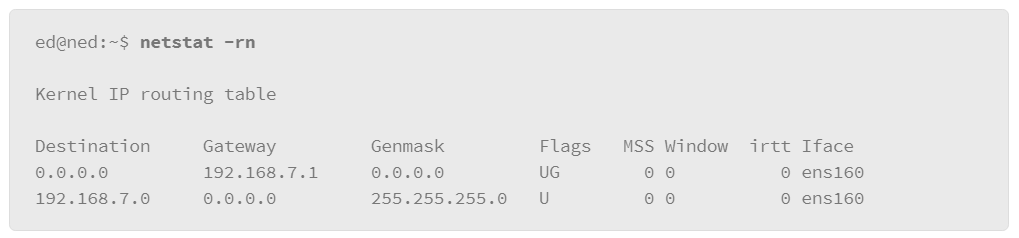

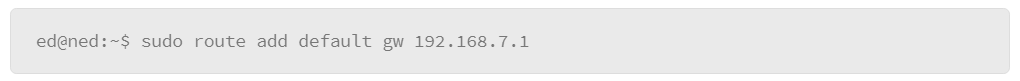

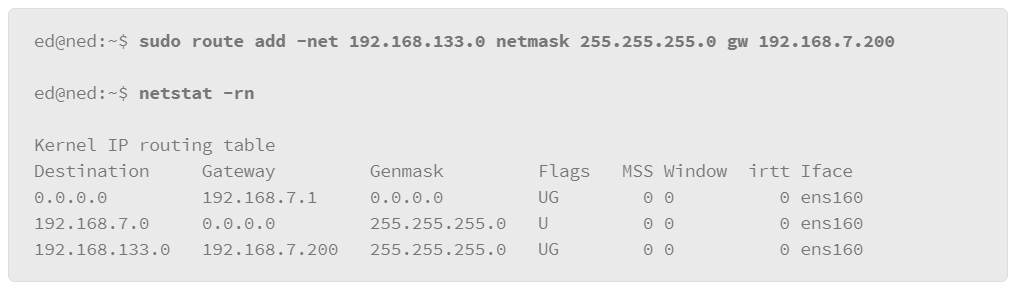

9.19 Networking

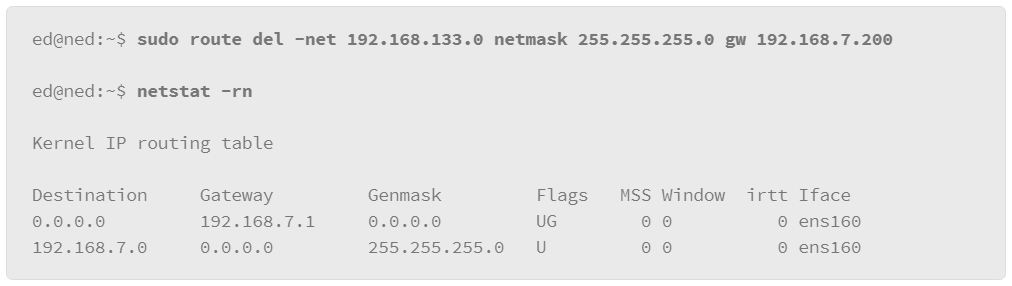

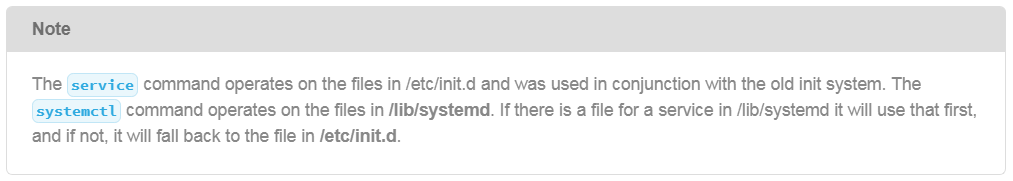

9.20 Managing Services in SysV Environments

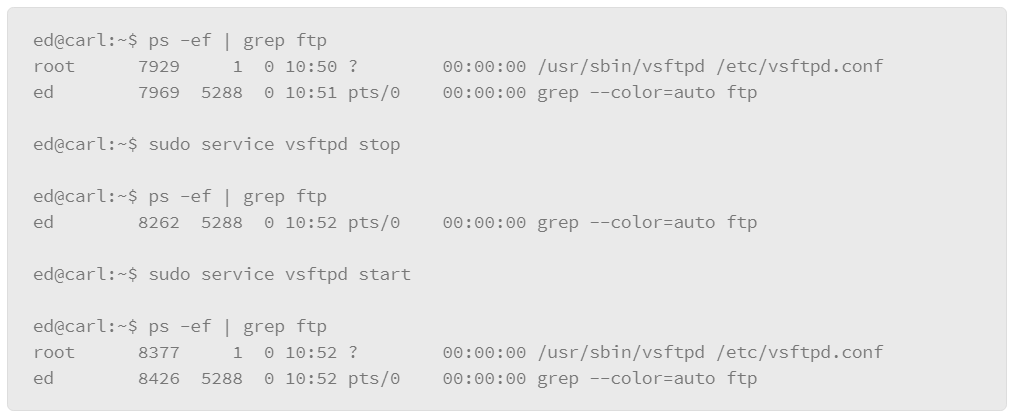

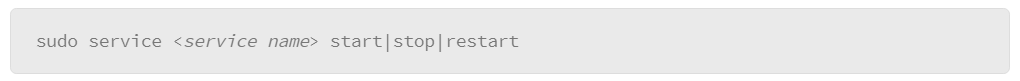

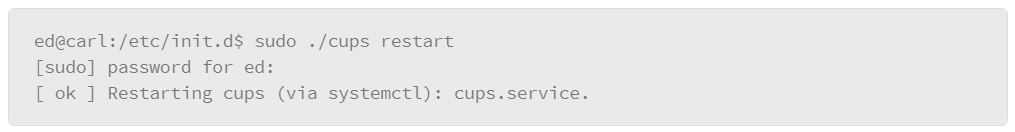

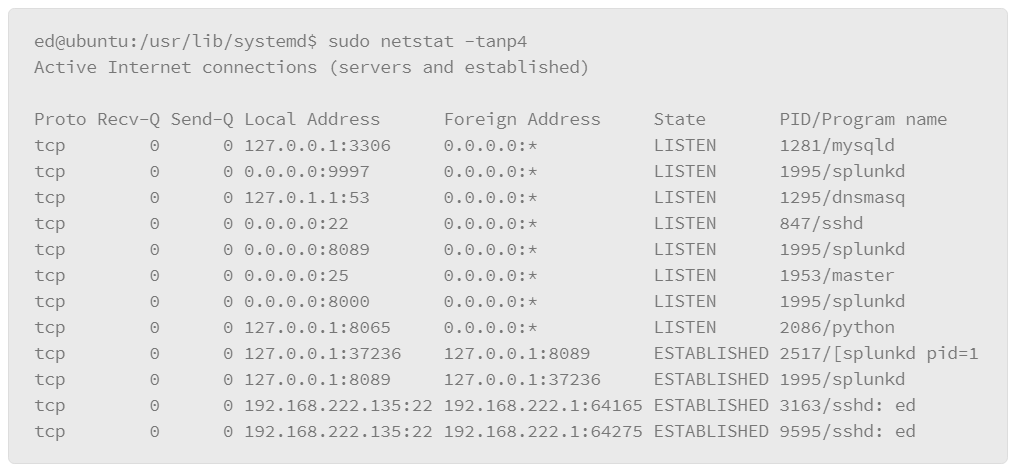

9.21 Viewing Running Network Services

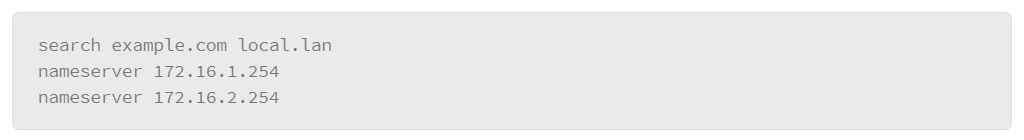

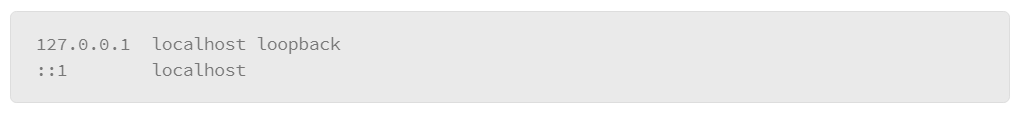

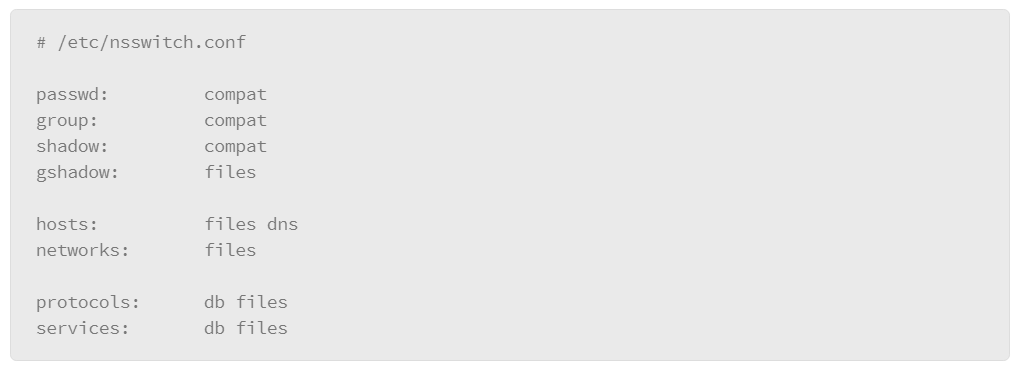

9.22 Name Resolution: DNS

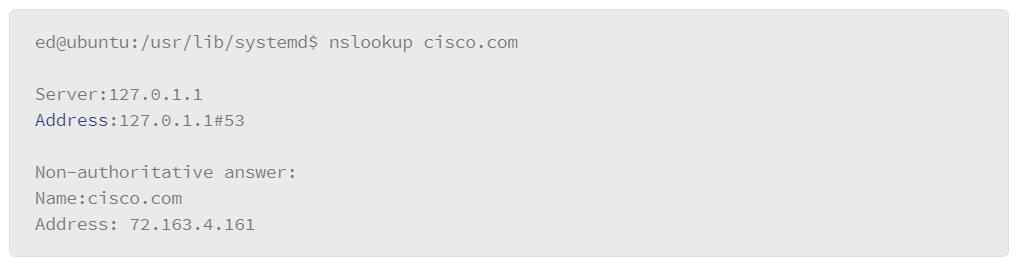

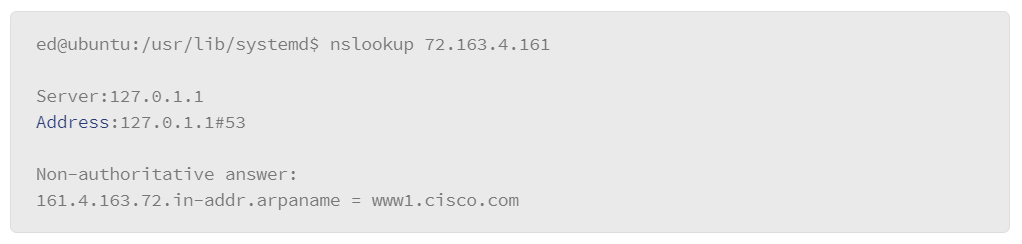

9.23 Testing Name Resolution

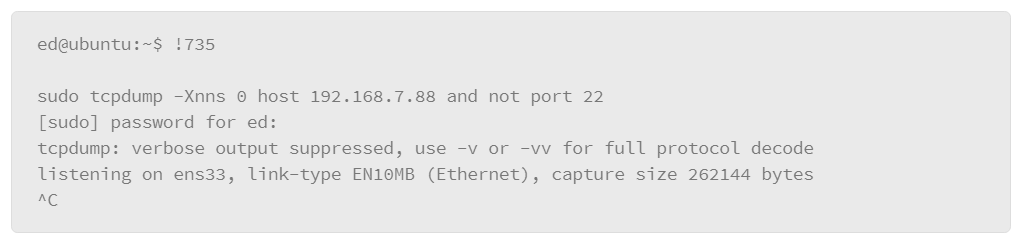

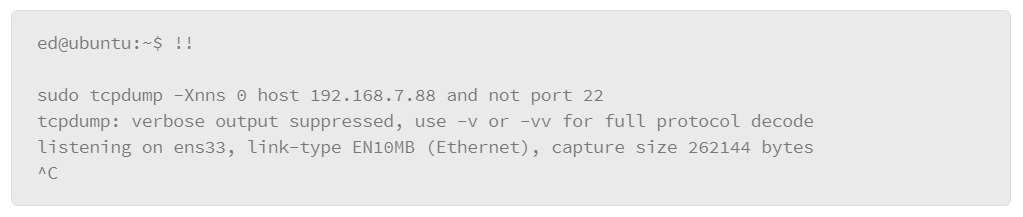

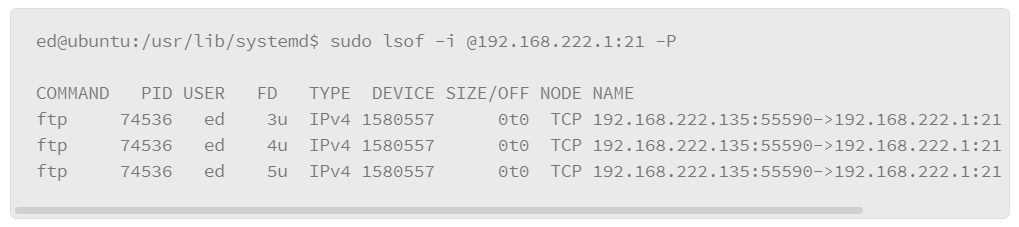

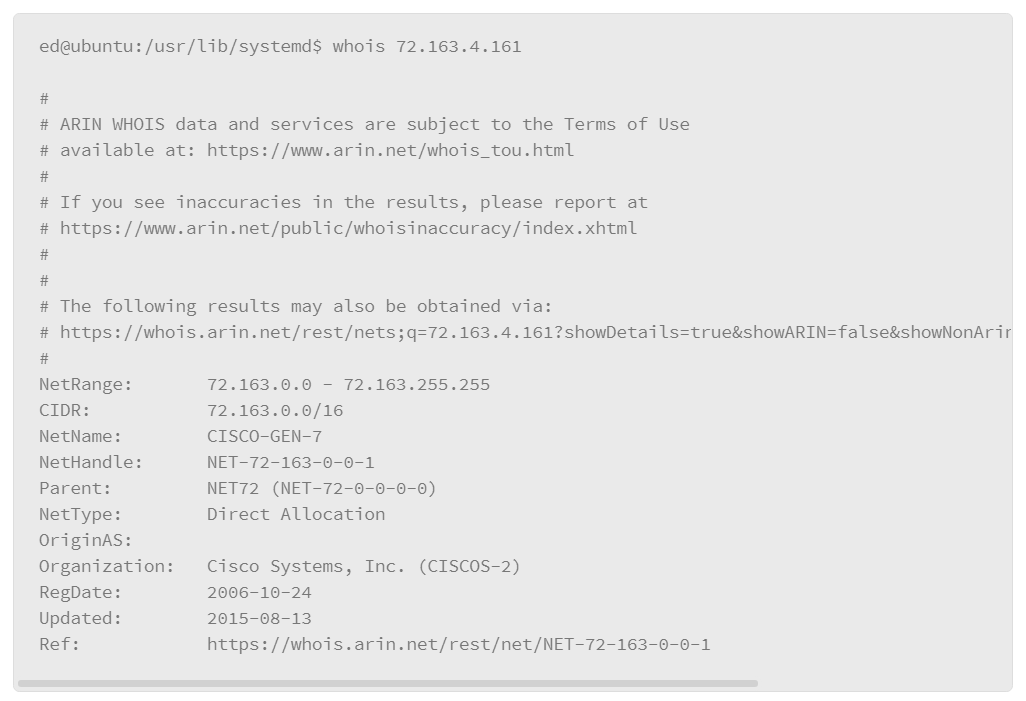

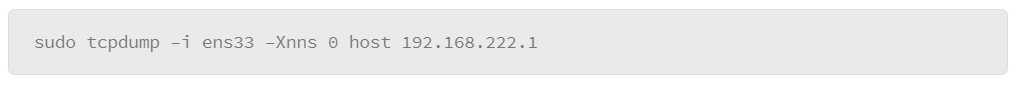

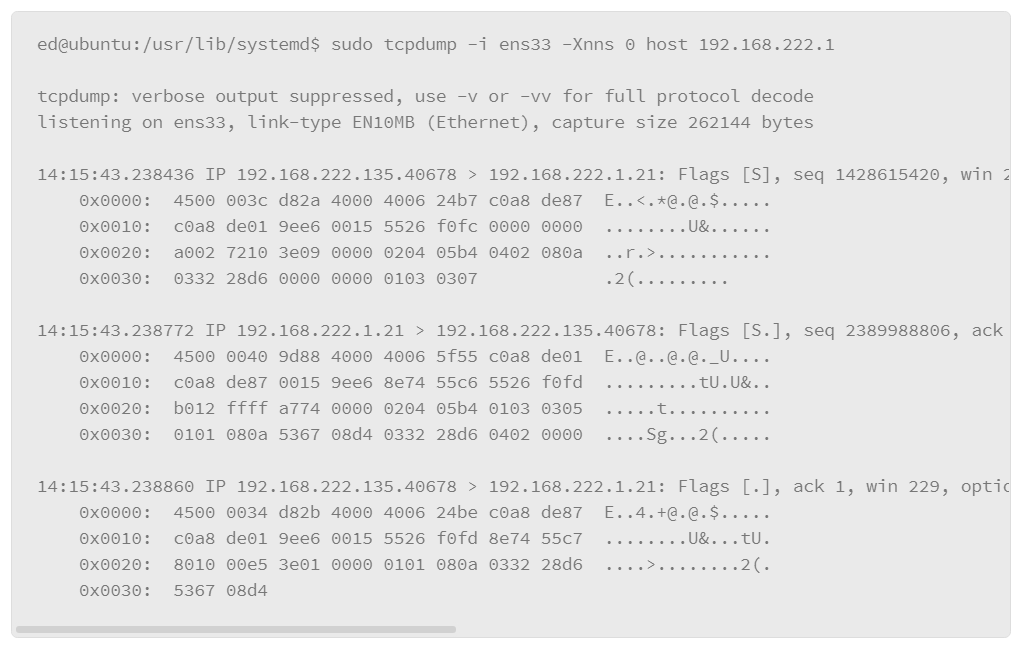

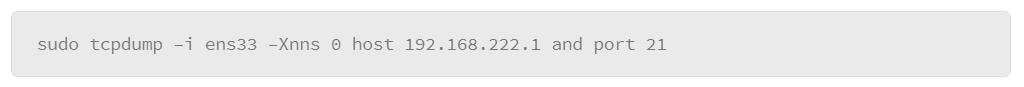

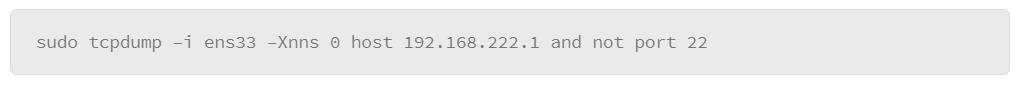

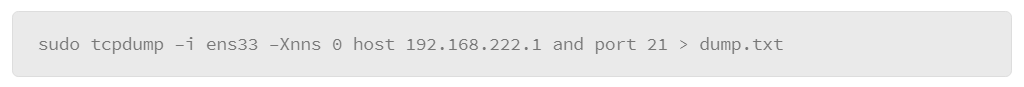

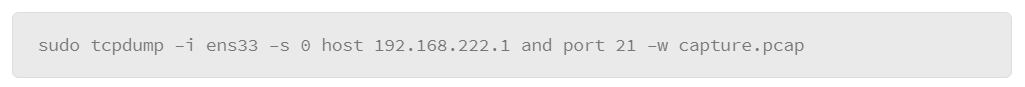

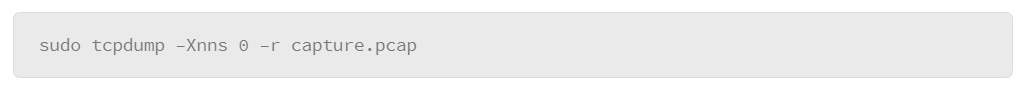

9.24 Viewing Network Traffic

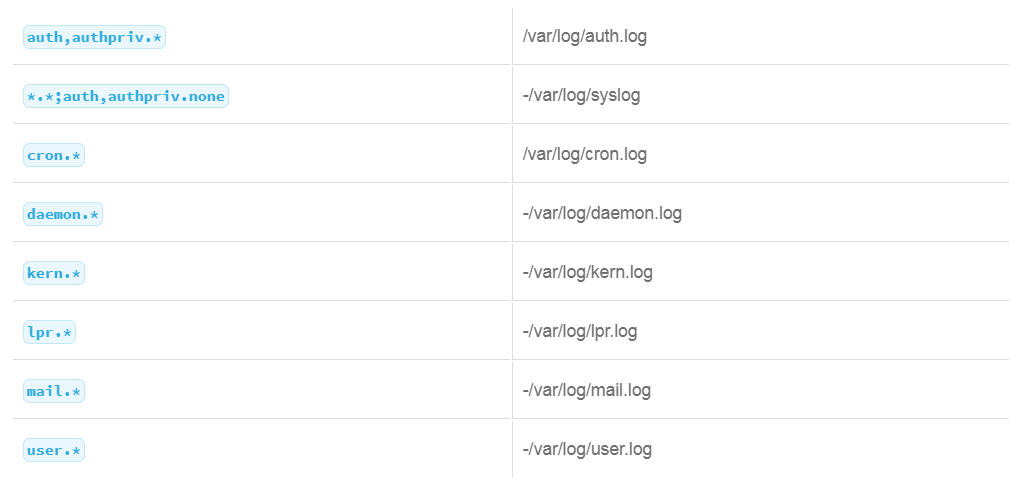

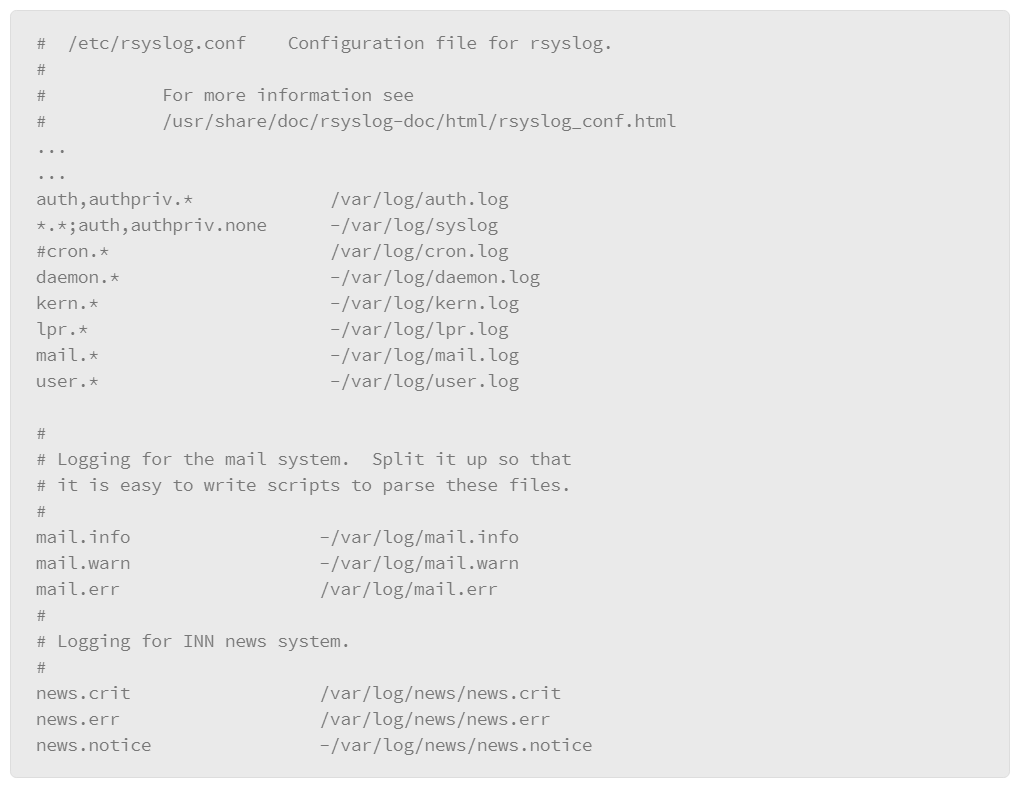

9.25 System Logs

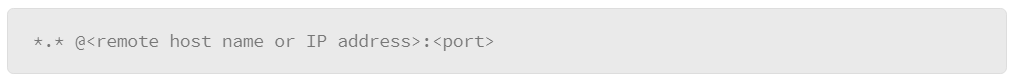

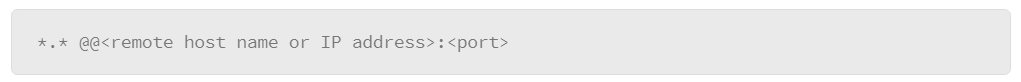

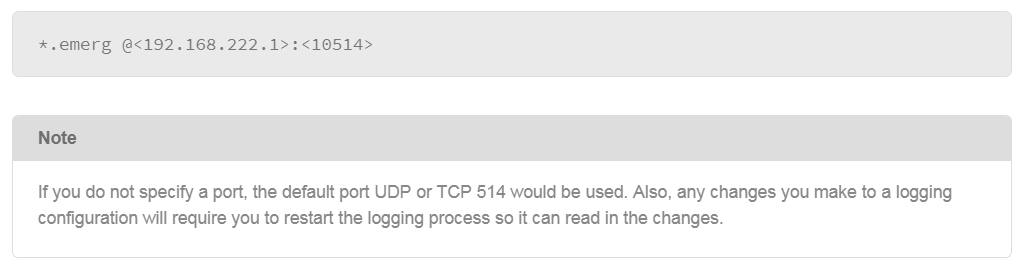

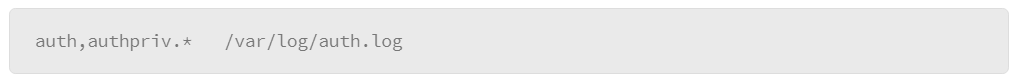

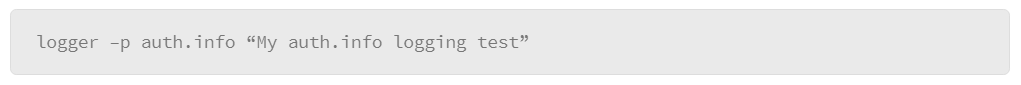

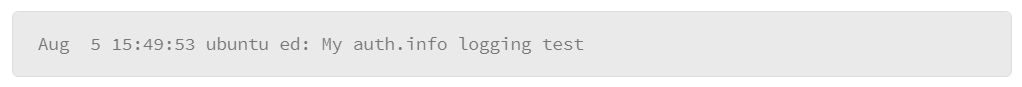

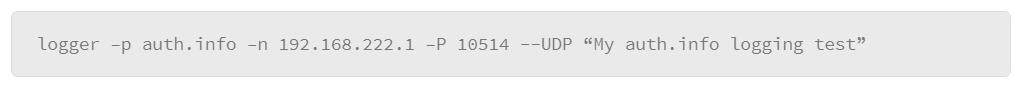

9.26 Configuring Remote syslog

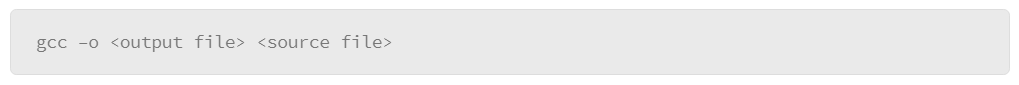

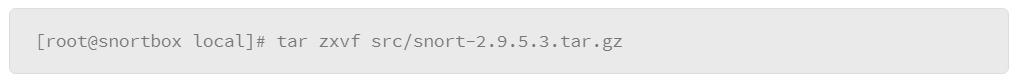

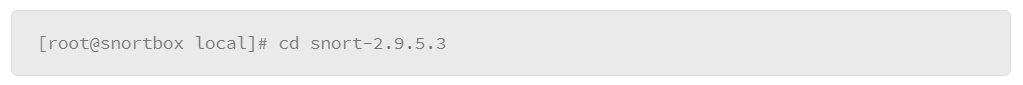

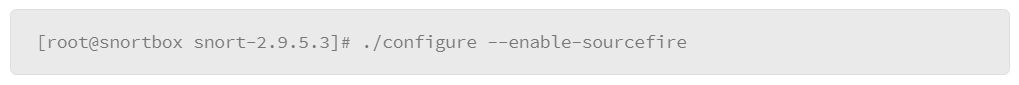

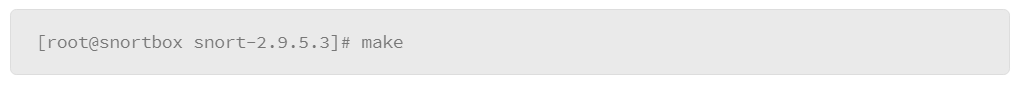

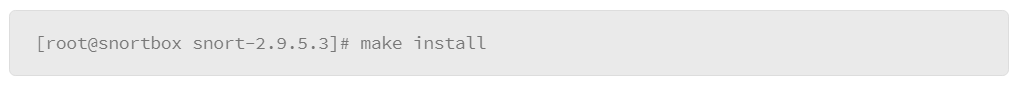

9.27 Running Software on Linux

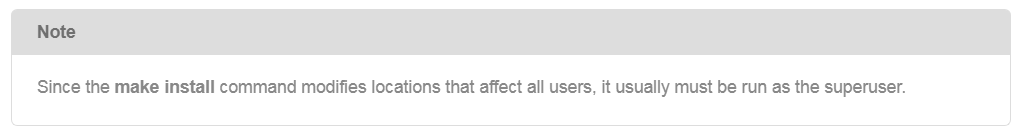

9.28 Executables vs. Interpreters

9.29 Using Package Managers to Install Software in Linux

9.30 System Applications

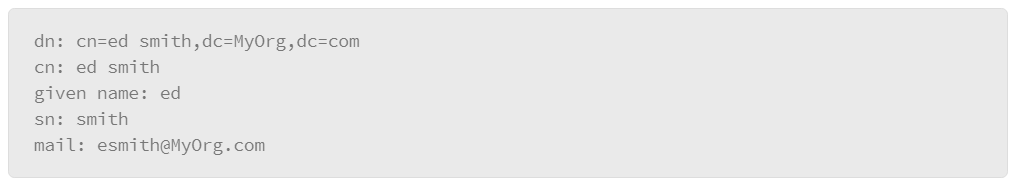

9.31 Lightweight Directory Access Protocol

History and Benefits of Linux

Linux traces its roots back to Unix, which was developed by AT&T labs as an operating system that was meant to improve software development. It did so by addressing problems with existing operating system platforms that traditionally challenged developers, such as file management and portability. However, because Unix was owned by AT&T, using Unix meant having to pay licensing fees and users were restricted by the terms of the license. Nonetheless, it was widely used and well known to developers and computer scientists because licensing fees were made very favorable to certain institutions such as universities, and it was a highly portable and efficient platform in its day.

Linux was started by Linus Torvalds as a project to create a Unix-like environment that he could run on his personal home computer because the systems at the university that he attended ran Unix. His implementation of Unix was completely re-written and he made it openly available to others with very limited restrictions under the terms of GNU public licensing or GPL guidelines. GPL allows the free distribution of software, and grants anyone the ability to modify the code if source code of the modification is made publicly available.

This model helped propel Linux development because code was visible to a wide audience and improvements were made public as well. Linux quickly became a robust operating system platform with large communities of users to support others at no cost.

Benefits of Linux

The open source nature of Linux makes it a highly cost-effective option. In addition to the operating system being freely available, much of the software that you can run on it is freely available. Virtually any application can be found of comparable quality to commercial counterparts.

The popularity of Linux means that there are plenty of resources available to help in the form of user communities, blogs, and discussion forums. There are also many resources that can be found online, including documentation, training, and videos to further extend the support options.

The Linux operating system is very stable and capable of running enterprise-scale production applications.

Linux Architecture

At the core of every Linux installation is the Linux kernel, the heart of the operating system. However, beyond the kernel there are applications that interface with the kernel to get things done. Over time, packages of Linux software have evolved that are maintained by like-minded users or communities. These packages are all based on Linux, but they may favor certain types of software components, desktop environments, or services. These packages have come to be known as distributions, and there are many to choose from. Some of the more common distributions include the following:

- Red Hat

- Debian

- Mandriva

- CentOS

- Ubuntu

These examples are all based on Linux, but their primary difference is the software that comes packaged with each. Usually, the choice of one over another is based on preference. Some may be better suited for enterprise applications, while others create friendlier desktop environments.

The Linux operating system is built on the concept of abstractions that are organized in a sequence of layers. The term “abstraction” in this context means that the details of how one layer will work are hidden from the other layers. Layers present interfaces that other layers can communicate with to perform tasks or request services. This layered architecture provides certain benefits: it simplifies software design because developers do not have to worry about how to interact with aspects already handled by other software components. The software simply requests what it needs from the other components and it is up to that component to perform the requested task and return a result to the calling component.

Access to the inner workings of a layer is limited to what the layer’s interface provides for communication. A component cannot directly manipulate what is under the control of another, which prevents users or higher-level software from potentially corrupting lower-level operations. For example, users cannot directly access hardware functions. Instead, a user would execute a command from the command line interface to move or copy a file, for example. The commands take care of performing the requested operation through the lower-level structures that are in charge of communicating with the disk drive.

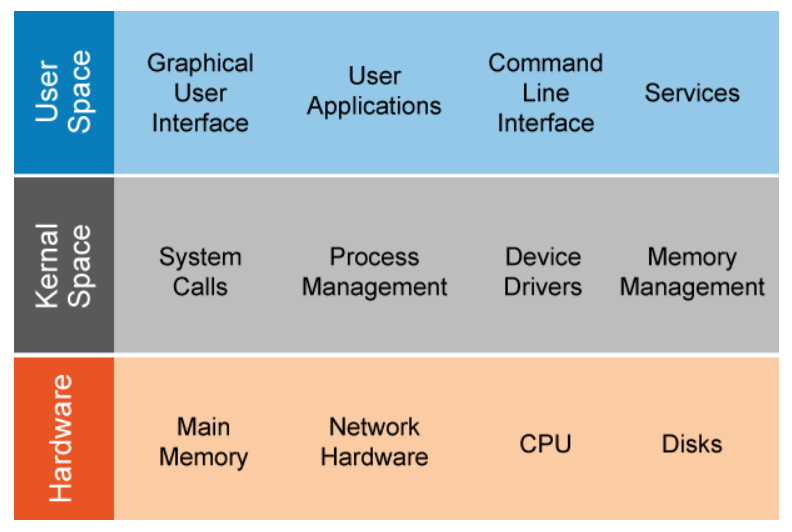

The high-level architecture of the Linux operating system consists of three primary components or layers:

- user space

- kernel space

- hardware

User Space

User space describes the system memory made available to run user processes. A user process can be any of the following:

- an application that is initiated by a user

- a background process that is initiated by a user application

- services

- the graphical desktop environment

- commands that run from a shell

User space processes are maintained in a separate memory space to prevent user processes from interfering with kernel processes. Interaction between the kernel and user space is performed through function calls and programming interfaces rather than allowing user processes to directly control anything in the kernel. Because of this separation, user processes that misbehave will typically not impact the rest of the system as the kernel maintains control of each process to prevent corruption of critical system functions.

Kernel Space

The kernel is the core of the Linux operating system. A section of the system’s main memory is reserved for the kernel to use. The kernel manages all the system resources.

- determines which processes can access the CPU

- manages the memory allocations for each running process

- is the interface between the user-space processes and the hardware.

Kernel/User Relationship to the Hardware

System hardware is insulated from direct manipulation by user processes because the kernel acts as the intermediary between the two. The kernel communicates with system hardware through device drivers. Maintaining this separation between user processes and hardware prevents user processes from potentially damaging the system in the event of a misbehaving process. However, users with sufficient privileges on the system can still cause damage by erasing critical files, for example.

The kernel is also responsible for managing multitasking by deciding which processes can access the CPU, a function that is called scheduling. When a user process is given time on the CPU, the kernel is responsible for mapping the virtual address space of the process to the physical address space of the main memory.

In addition, the kernel must load and unload special memory, which are called registers, within the CPU. These registers are used for extremely fast computation and storage. However, since each user process must be kept separate by the kernel, a function that is called context switching is implemented to temporarily unload the registers until the next time that process needs the CPU.

Linux File System Overview

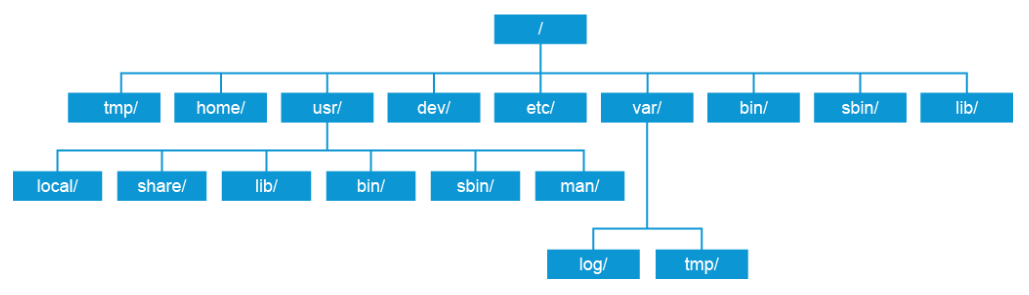

Linux maintains a fairly standard file system structure, making navigation around different hosts easier even if they are running different Linux distributions. There are some minor differences between distributions, but navigating around the differences can be easily overcome once you familiarize yourself with the basic structure, as shown in the figure below.

In Linux, the file system structure begins with the root directory, which is expressed with a single forward slash (/) character. Everything else in the file system, including other drives or peripheral devices, will reside somewhere below the root.

Different Linux distributions may reserve subdirectories for you to mount drives or other storage media. For example, if you mount a CD-ROM drive in an Ubuntu installation, it will be mounted in a directory that is called /media by default. Other distributions may include a directory that is called /mnt for mounting storage media. You can also mount storage media anywhere that you want as long as your user account has permission to write to the directory where you want to mount it. The location used to mount storage media is known as the “mount point.”

Different Linux distributions may have slightly different file system structures, but the core structure is common to all distributions. These directory locations are used to store specific types of data as follows:

- /tmp: Stores temporary files. It is often used as a workspace by applications. Users should not use this directory to store anything of any importance because many Linux distributions wipe this directory on boot, and in a default installation, any user is able to read and write to this directory. Attackers may use this folder to store malware, often as the first stage of an attack, because it is a consistent and permissive directory across Linux installations.

- /home: Location where the personal directories for users are stored. These directories should be secured because they often contain private and sensitive information (like configuration files with password, SSH private identity keys, and user files).

- /usr: Used to store user-space programs and data. The reason for the /usr directory is mostly historical, but in modern Linux installations it contains several subdirectories:

- /usr/local: A location set aside for administrators to install software.

- /usr/share: Originally, this directory was used to share files between hosts that could be used on different Linux/Unix platforms. It was designed as a workaround when disk space was at a premium. Today's systems have no such constraints, so it is no longer used in that capacity.

- /usr/lib: Stores library files that executable programs need to access at run time

- /usr/bin and /usr/sbin: These directories are used to store binary (compiled) executable files. These files make up the bulk of the Linux operating system. The /usr/sbin was traditionally reserved for files that can only be used by root, but that distinction no longer applies.

- /usr/man: This directory is used to store the manual pages, AKA “man pages,” that contain the documentation for important files in the operating system and installed applications. - /dev: Contains device files. Hardware and virtual devices, such as terminals, appear as files to the operating system. When Linux needs to access a device, it often does so by interacting through device files. Unlike other directories here, this folder is "special" in that the files and folders inside are representations of hardware and objects in the kernel. For example, although it appears to be a file, /dev/sda may point to your first hard disk drive, and /dev/urandom is a secure random number generator.

- /etc: Stores system configuration files for the operating system and services. For example, SSL keys for web servers, private keys for SSH servers, and user accounts and passwords are kept here. This directory must be kept secure to keep the system secure.

- /var: This directory is used by the operating system and applications to store runtime data and log files. There are several subdirectories that are located here, two of which are common to all Linux distributions:

- /var/log: Used by the operating system and applications to store log files. At a minimum, non-privileged users must be prevented from writing to this folder. Otherwise, the integrity of the log files would be compromised after an attack.

- /var/tmp: This directory is used as a workspace to store temporary runtime data for the operating system and running applications. - /bin and /sbin: These directories are used to store system binary files. Traditionally, the files stored here were files that were required to boot the operating system. All other system files were stored in the /usr/bin and /usr/sbin directories, which is no longer true as many files found in /usr/bin and /usr/sbin are required at boot time.

- /lib: Stores library files that must be available to executable files at run time.

Special File System Structures

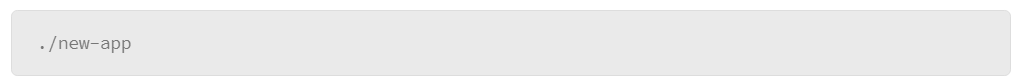

When you navigate the file system from the command line, you are likely to encounter entries in directory listings in the form of a dot (.) or two dots (..). These structures represent important constructs in the file system. First, the single dot (.), is a reference to the current directory. The significance of this is that if, for example, you want to execute a file in the current directory, you may be surprised to find that the system will not find the file even if you are in the directory the file resides in. The reason for this is that Linux searches specific directories when you execute something.

Note:

The set of directories that Linux searches for command execution is stored in an environment variable that is called $PATH. The path is assigned to you at login. You can modify the path that is assigned to you by editing your user profile. If you wish to see the path for your environment, execute the following command: echo $PATH The output will show a colon-separated list of the directories in your path.

Therefore, to execute a file that is not in the path, you would start with the reference to the current directory, the dot (.) followed by a forward slash (/), and the file name. For example, you want to compile a tool that you downloaded to your home directory, called new-app. You created a subdirectory in your home directory to store the components that are needed to compile the application. When ready, enter the directory that was created and compile the application, which will produce an executable file that is called new-app in that directory. To execute the application, enter the following in the command prompt:

The double dot (..) refers to the parent directory of the current directory. For example, user Joe has a home directory of /home/joe. Joe creates a subdirectory to download a tool that is called newapp20. The full path to this directory is /home/joe/newapp20. While inside that directory, Joe decides to navigate back up to his home directory. To do so, he can use the double dot reference:

Joe is now working in the /home/joe directory. The command that he used is the same as the following:

One last structure that you may encounter in documentation or reference material is the tilde (~). The tilde is a shortcut that represents the current user’s home directory. Returning to the example of the user Joe, who wanted to navigate to his home directory, another alternative is to use the tilde,as follows:

This command puts him back in his home directory: /home/joe

Fully Qualified vs. Relative File References

You have two options for navigating the Linux file system. You can use a fully qualified reference to your destination or you can use a relative reference. The fully qualified reference means that you explicitly state the location beginning with the root of the file system.

Fully qualified references always start with a forward slash (/), which represents the root. For example, the fully qualified reference to Joe’s home directory is /home/joe, which is workable as long as the file system locations are not too lengthy. Consider copying a file from one location to another using fully qualified path names:

The benefit of this method is that copying this file to the specified location will work from anywhere in the file system. However, due to the length of the file location references, it is cumbersome to type, especially if a command can be repeated.

An alternative is to use relative references. A relative reference lets you specify a location relative to some starting point other than root. For example, if a file that you wish to copy is in the directory that you are currently working in, you can omit the path and specify the file name and the destination. In this scenario, Joe is in his Downloads directory and he just downloaded a .pcap file. He uses the following command to copy the file to a directory called caps, under his home directory where he stores his .pcap files:

In this example, Joe knows that his Downloads directory is in his home directory: /home/joe. The caps directory is also there. Since Joe is currently in the Downloads directory, he uses the double dots (..) to go up to the parent directory, and from there he moves down to the caps directory.

Unlike fully qualified directory references, relative references have no leading forward slash. One last note on relative references is that you can also leverage the tilde (~), which points to your home directory. In the previous example, where Joe wants to copy a .pcap file from his Downloads directory to the caps directory, he could have used the following command instead:

How Devices Are Represented as Files in the Linux File System

Devices in the Linux file system are represented as files. You will find them in the /dev directory. Usually, users don’t interact with device files directly. Device files are most often accessed by applications that require the services of a device. However, users that write scripts or code applications may need to access devices, so it is important to understand the concept of devices being represented as files.

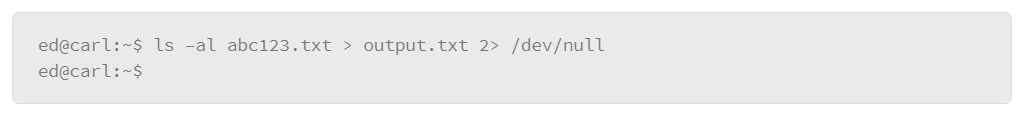

One example of a device that is used frequently in scripting is /dev/null, which is a device that represents nothing, so sending data to it is, in effect, discarding the data. Consider the following example:

Without the reference to /dev/null, the echo command would send the string test data to the terminal window where you entered the command. However, directing the output to /dev/null discards the data, so the echo command would not display the string in the terminal window as it normally would.

Devices can be classified in one of the following categories:

- Block: Devices that process data in fixed chunks, for example, disk drives or other forms of storage devices.

- Character: Devices that work with data streams. One such device is /dev/null. Directly connected printers are another example.

- Pipe: Sometimes referred to as “named pipes.” These devices operate in a manner similar to character devices. However, the data stream is directed to another process rather than a device file or driver.

- Sockets: These devices are unique in that they are not usually found in the /dev directory. They are used for interprocess communication such as network communication.

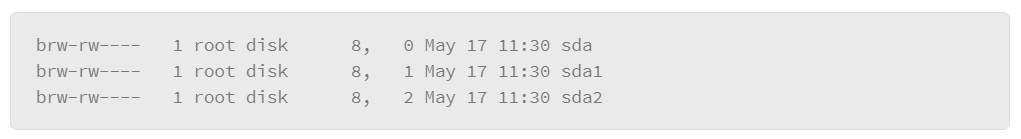

You will be able to tell a device’s type by listing the files in the /dev directory with file details. The following command lists files in a directory with the file details:

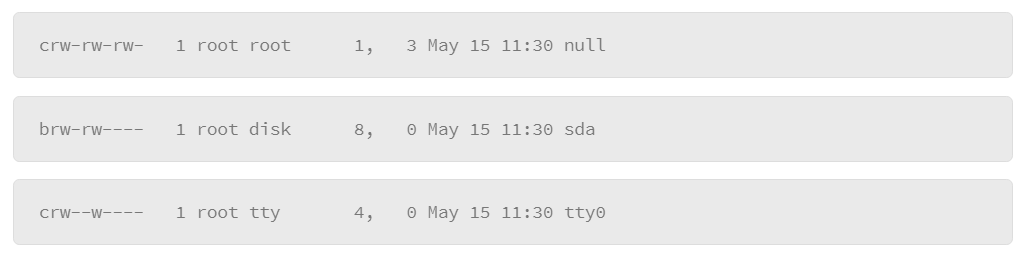

The l parameter lists the details, and the a parameter lists all files, including filenames that start with a dot (.). Here are some examples of device file entries:

The first character of the entry specifies the type. For example, the c represents a character type of device, and the b represents a block type of device.

Some device types that you should be familiar with include disk devices. In some commands or configuration files, you will need to specify a disk drive reference. Complete by entering the file name of the device to reference.

In Linux, disks are often identified by the letters sd, followed by a third letter. For example, the first disk drive would be referred to as sda. The next would be sdb. The three-letter code refers to the entire disk drive. However, disks are often divided into discreet partitions, so a number that follows the three-letter code of the disk indicates the sequence of partitions. For example:

Here, you see an entry for a disk drive that is called “sda,” which contains two partitions: sda1 and sda2. There are many types of devices and each has its unique identification code.

Basic File System Navigation and Management Commands

File Properties and Permissions

File properties describe the characteristics of a file or directory. The command that you use to list files and display their properties is as follows:

The –l parameter instructs the command to display the listed files with their properties. The [files] parameter lets you specify which directory or file names to list. If you omit the [files] parameter, the ls command will list all the files in the current directory.

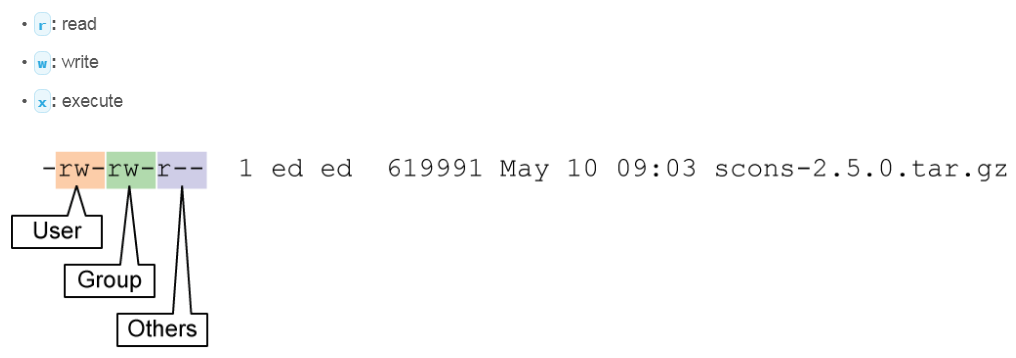

The following information is contained in the ls –l command output:

- File type: In the example, each file shows a dash (-) character to indicate regular files. For device files, you may see the letter c for character streaming devices, or b for block devices. For directories, you would see the letter d.

- Permissions: This section is represented by the next nine columns of characters. They are organized in three groups where the first group represents the user’s permissions, the next is the group permissions, and the third is the permissions that are granted to all others.

- Links: The number of hard links to the file or for directories, it represents the number of directories that it contains, including the current directory (.) and the parent directory (..).

- Owner: the username of the file or directory owner

- Group: the group that the file or directory owner belongs to

- File size: the file size in bytes, unless it is followed by a letter (k for kilobyte, m for megabyte, or g for gigabyte)

- Time stamp: By default, the three columns that follow the file size represent the last time that the file was modified. The first value is the month, the next is the date, and the last is the time in hours and minutes. If the file is very old, the time is replaced with the year.

- File name: the file or directory name

Many of the problems that users may face, relative to files and file management, can be traced to issues with file permissions and file ownership. Therefore, it is important to understand these concepts and be familiar with some of the tools that you can use to manage file permissions and ownership.

Permissions

File permissions refer to the actions that a user or members of a user group are allowed to perform on a file or directory. There are three actions that can be configured for a file:

In the ls –l command output, file permissions are listed in the nine columns of characters that follow the first column. This area is divided into three sections:

- The first section describes the actions that the owner of the file is allowed to perform. In the example, you see the letters r and w, indicating that the user is allowed to read and write to the file.

- The second section identifies the actions that the users in the group assigned to the file can perform. Once again, you see the letters r and w, indicating that the users in the group who are assigned to the file can read and write to the file.

- The third section indicates the actions that all other users are allowed to perform on the file. In the example, only the letter r is displayed, indicating that everyone else can only read the file.

- Note that Linux treats file permissions as a hierarchy. For example, without permissions to read the directory, you would not be able to see a list of the files that are inside, and without execute permissions on the directory, you would not be able to open the files that are inside.

The file owner and user root can modify the permission properties of the file.

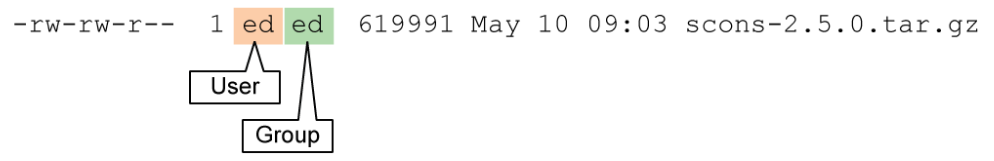

Ownership

The concept of file ownership in Linux is a key security measure that is built into the operating system, which gives administrators very granular control over what people can access on the system. For example, the user root has access to virtually everything in the operating system. You don’t want users with lesser privileges to have that degree of access. File ownership can also be used as a mechanism for preventing one user from accessing sensitive items that belong to another user.

The output from the ls –l command displays the file ownership properties as follows:

The user that is identified in the user field is considered the owner of the file. And the group that is indicated in the group field identifies the user group that is assigned to the file. Access to the file can be granted to members of the assigned group. The file owner and the root user can modify the ownership properties of the file.

Editing File Properties

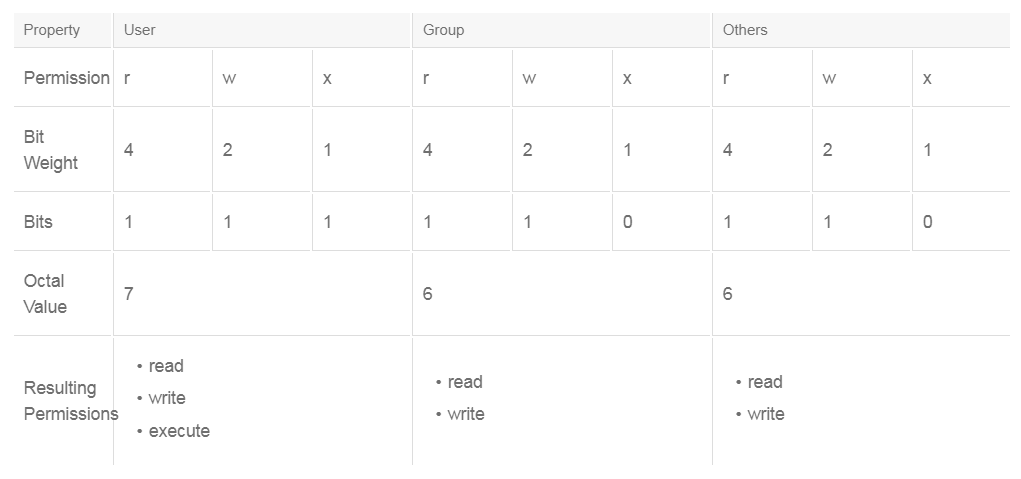

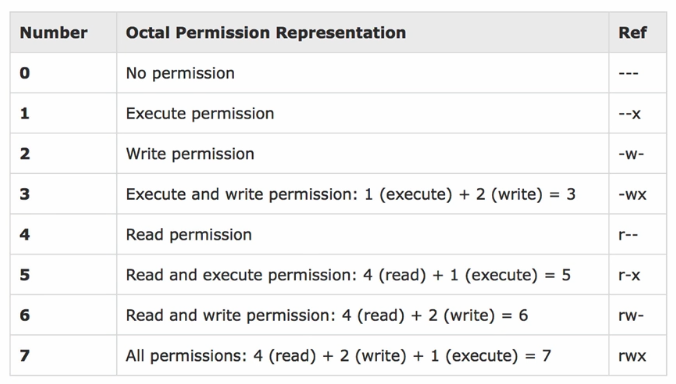

Linux provides several commands that you can use to manage file permissions and ownership. The chmod command has many options to modify file permissions. One method is to use an octal numbering scheme that works because the permission settings use three values for each of the access classes: user, group, and others. Therefore, the three values can be represented as bits in an octal number. An example of how this method works is as follows:

The first number sets the permission bits for the user, the next sets the bits for the group, and the last sets the bits for others. In this example, the permissions would be set as follows:

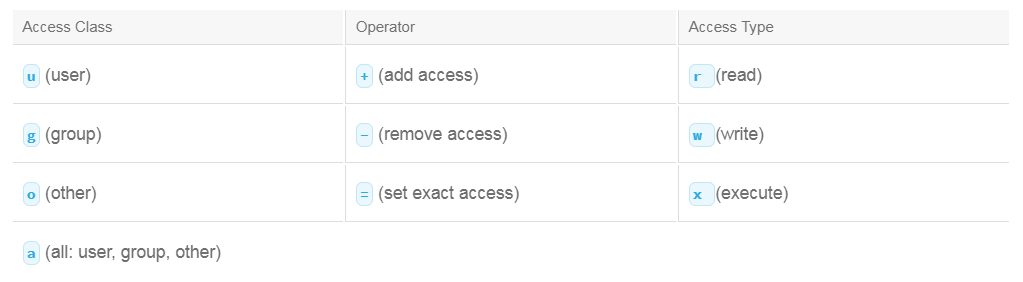

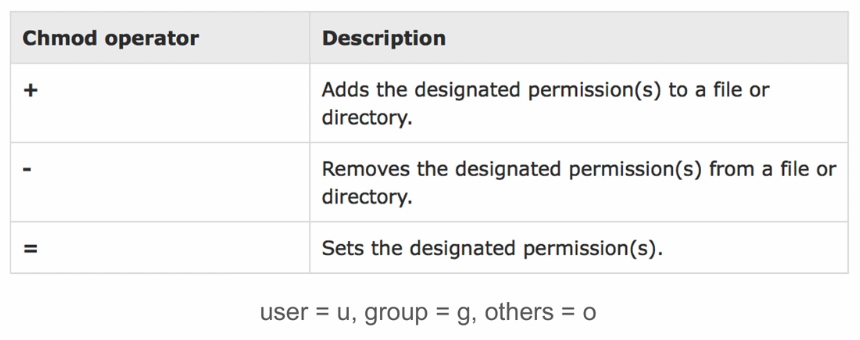

Rather than using the numeric or absolute form, you can use the symbolic form. The table outlines the various symbols that can be used and their meanings:

With the symbolic method, you can use a symbol to represent the access class and the access type you want to modify. You specify the operator to set the state of the access type by placing it in front of the access type symbol. When the access type and access class are chosen, the selections are affected by the command. The exception to this rule is when you use the = operator. If you omit an access class, the a or all access class is implied.

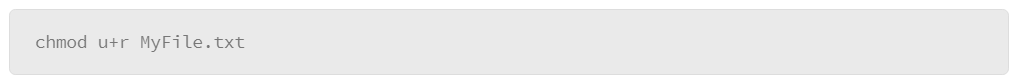

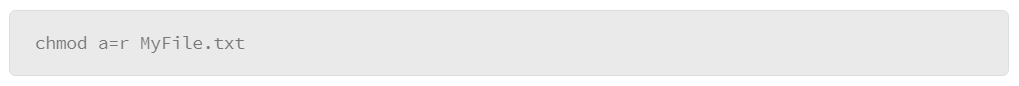

The example that follows sets the user access class to the file called MyFile.txt to read only:

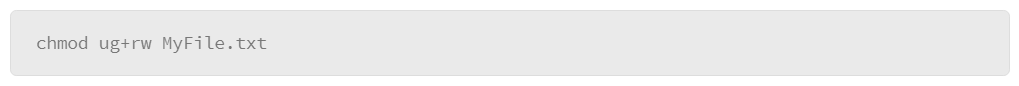

This example sets the access type to read and write for both the user and the group:

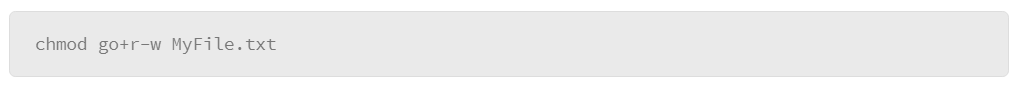

The next example sets the access type to read and removes write access to the group and others:

The last example sets all users access type to read only:

The difference between the last example and the others is that this syntax resets any access type bits that were set. In the other examples, the command only affects the access types that are called out in the command. If, in the first example, the write bit for the user was already set, it would remain set.

Root and Sudo

In a Linux installation, the root user, also known as the super-user, has authority over all. It is a powerful account, and if used improperly, could cause a lot of damage. Or, if compromised, an attacker can do anything on the compromised host. Regular non-root users cannot do quite as much damage because of the permission and ownership structure of the Linux file system.

Because of the great power of the root user, many modern Linux distributions limit the use of the root account. In fact, some distributions make it extremely difficult to even enable the root account, which makes good sense as a security measure, but there are many system functions that only the root user can do, making the system impossible to use if root access is eliminated completely.

Modern Linux distributions provide a mechanism for controlling root-level access that is called sudo. It provides a system for delegating authority on a very granular basis. For example, you can allow users to run commands as root or limit them to certain commands. It also is capable of very granular logging if you enable this capability in its configuration file. This feature of sudo leaves a very detailed audit trail so that you can tell who executed commands as root and when.

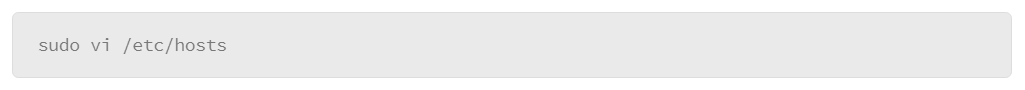

Using sudo is really rather simple; you enter the string sudo at the command prompt, followed by the command that you wish to execute. For example:

vi is a text-editing application. Normally, the file /etc/hosts is only writable by root. If you attempt to write to this file without including the sudo command, you would see a system message that permission to write to the file is denied.

When you execute the sudo command, you will be prompted for your password, which starts a five-minute session during which you are allowed to enter commands with root authority. If the terminal where you issued the sudo command is left unattended for more than five minutes, you will be asked to authenticate again in order to invoke another sudo command.

As the administrator of a Linux installation, you should get used to using sudo, because many of the administrative tasks you would need to do require root access.

Disks and File Systems

From the file system perspective, everything in Linux appears as a single structure with its foundation being root, even if the system contains multiple disk drives or other types of storage media, such as optical drives. They are mounted to the file system at mount points that begin in some subdirectory off root. In reality, physical disks and optical drives are unique entities that store or allow you to read data.

Disk drives are one of the most important hardware devices in the system, because they store the file system itself. Understanding their structure is important because you may need to delve beyond the file system to perform certain administrative tasks or analyze a host.

Disk Partitions

Disk drives must be structured in a logical manner in order for the operating system to be able to find things on the drive. One of the structures that are used for organizing data on a disk is known as a partition. Partitions are areas of the physical disk that are reserved for storing data. You can see this structure in the device directory, /dev, when you list the disk devices. For example, the physical disk will typically have a three-letter code that is assigned to it, starting with the letters “sd.” The third letter represents the sequence of disks where the first disk would be called sda, the second sdb, and so on.

Disk partitions are identified by a number following the three-letter code. For example:

- /dev/sda: The first physical disk

- /dev/sda1: The first partition of the first physical disk

- /dev/sda2: The second partition of the first physical disk

A structure on the disk that is known as the “partition table” is where partitions are managed. Partition tables contain the code that is required to boot a host and they outline where disk partitions start and end. Several Linux utilities are available to manage the partition table, such as parted, gparted, fdisk, and gdisk, to name a few. Some are designed to work with a specific type of partition table (fdisk only supports the MBR type) and others can work with both the commonly used partition table types: MBR and GPT. Also, gparted is a graphical version of parted.

The MBR partition table type is the older, more traditional type. It is the most widely compatible, but it has some limitations regarding the size of disk drives that it supports and the number of partitions that you can host on a disk. The limit is four partitions, but there are ways to get around that limit by using different types of partitions. Also, a disk may only have one MBR. If the MBR were to get corrupted, it could render the entire disk unreadable.

The other type of partition is known as GPT, and it is the newer of the two types. GPT removes the restrictions on disk size and number of partitions. It also replicates itself on the disk several times, so that if the primary GPT were to become corrupted, the disk can revert to one of the copies and continue operating.

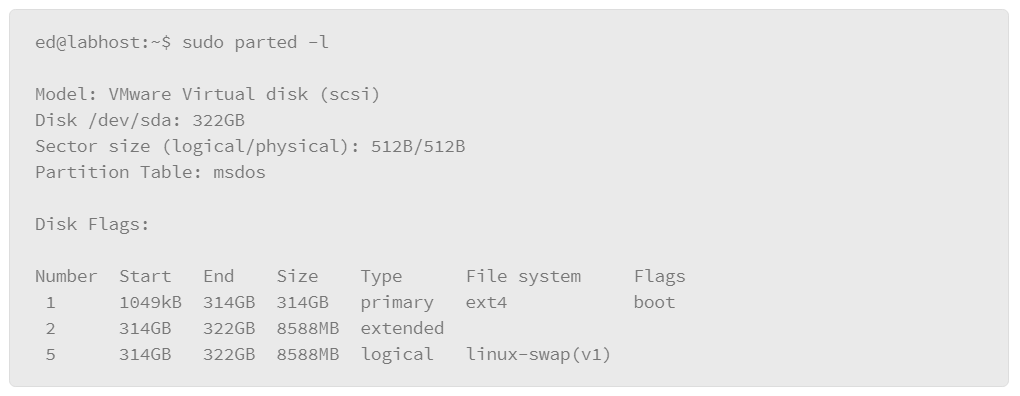

The following example uses the parted command with the –l parameter to list partition table information.

In this example, the host has a single disk that is mounted, and its device name is /dev/sda. The partition table type is identified as msdos, which means that it is using the MBR partition table format. Then it lists the partitions on the drive. In this case, it has three partitions numbered 1, 2, and 5.

The parted tool and the other tools allow you to not only view partition information, but also to manage partitions. For example, you can create partitions on new disks or change the size of existing partitions. Managing partitions can have severe consequences if not done with care and planning because it can wipe the contents of an entire disk. Approach with due care and make sure that you back up important data before managing partitions.

File System Types

File systems themselves come in several varieties. The native Linux file system is known as extended file system or ext. This file system type has been updated over the years; the most current version is ext4. Linux continues to support the two previous versions: ext2 and ext3. There are several file system types that you are likely to encounter in Linux environments:

- ext2, ext3 and ext4: Considered native Linux file systems, ext4 is the most current. Linux maintains backward compatibility with the previous versions as well.

- NTFS: Used by modern Microsoft Windows environments, this complex file system supports versatile permissions, large disks, and other advanced features.

- FAT16, FAT32, exFAT: FAT was the native file system in older Microsoft environments. It has mostly been replaced by NTFS but remains as a fairly common file system type since many USB storage devices come formatted with the FAT file system. FAT file systems are Linux compatible, but lack features such as permissions and support for large disks.

- ISO 9660 and JOLIET: File system standards that are used on optical media, like DVDs and CDs.

- HFS+: The file system that is used by Apple systems running OS X. Linux ships with drivers that can read and write to this file system, so there is compatibility between Linux and HFS+.

- Swap: A special type of file system that is used in Linux swap partitions. The swap partition is disk space that is reserved for the system to use when it needs to free memory resources. The system’s main memory (RAM) is very fast compared to disk drives, so, ideally, you will want to run everything in main memory. However, if the system starts to run low on main memory, it can free up memory resources by moving data in memory to the swap partition. So, the swap space is not really a file system at all. It is directly addressable space on a disk drive to temporarily dump content from main memory. When a system’s main memory resources are oversubscribed, you will find that the system’s performance will degrade substantially because it is moving data much more frequently between main memory and the swap disk.

Mounting Devices

Another aspect of managing disks is understanding how they connect to the file system and how you can determine what is mounted to the file system. Linux will try to mount the disks it sees when it boots. You can see details devices that have been previously mounted in the /etc/fstab file. If you attempt to mount a device, it will reference this file to get the mount configuration for the device. Or you can add the –o option to override the configuration parameters in /etc/fstab and supply your own.

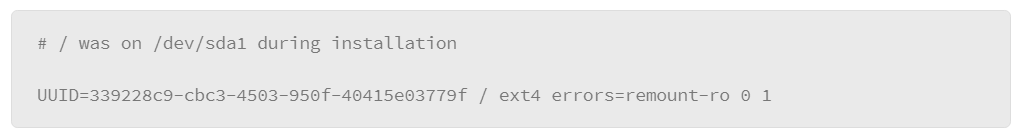

One thing to note is that newer implementations of the /etc/fstab file will list devices by their UUID numbers instead of the device name. A more precise way of identifying devices because device names may change. The example that follows shows an entry in /etc/fstab.

Note that there are two lines that are related to the same device. The first line is a comment and has no effect on how the system operates. It is there to help users understand what the line that follows indicates. The second line contains a series of fields that are separated by spaces or tabs. These fields contain the device’s parameters at mount time, as follows:

- UUID of the device: The comment above it indicates the device file that it refers to. In the example that device is /dev/sda1. When the filesystem is created, the UUID is generated and stored in the metadata on the device itself. While names like /dev/sda may change if the device is plugged in differently, the UUID will allow Linux to better track the device.

- Mount point: In the example the mount point is root (/), which indicates where the root of the file system is located.

- File system type: The example lists this device as having the ext4 file system type.

- Options: The options indicate operating parameters of the device. In the example, the option that is shown specifies what to do if the device encounters an error condition. In this case, if the device begins encountering errors, Linux will remount the device in read-only mode, so the system can continue to operate.

- Dump frequency: The second-to-last column (shown as a zero) is a deprecated field that no longer has relevance in modern Linux environments.

- Pass number: The final column (shown as a one) configures the order that devices should be mounted. The root file system is the first partition to be loaded, so it is marked with a one. Other file systems would be configured with a two, which indicates they can be mounted anytime after the root filesystem.

To manually mount a device, use the mount command. The basic syntax is as follows:

The –t option lets you indicate the file system type of the device. It is not required, since Linux can generally figure out the type on its own. The next option is to specify the device name, for example, /dev/sdb. The last option is to specify the mount point. Many Linux distributions set aside a directory that is called /media as an organized place to mount devices, but you can mount a device anywhere on the system that your user account is permitted to access.

System Initialization

The general sequence of events in the Linux boot process is as follows:

- hardware checks

- device bus discovery

- device discovery

- kernel sub-system initializes

- root file system mounts

- start user processes

The key component that starts the boot process is the boot loader. There are many boot loaders available to choose from, but the two most common are GRUB and LILO. Because no drivers to access disk drives are available at start time, the boot loader must interact with the system’s BIOS or its more modern counterpart UEFI, to access the disk hardware. The BIOS/UEFI resides in the system’s firmware. It contains enough code to perform some basic system checks and initialization of system peripherals at boot time. One of the checks that it performs is to find the system start disk and read its partition table, which contains a small bootstrap program. The boot loader’s primary job is to find the kernel on the startup disk and load the kernel into memory so that it can begin booting the system.

Boot parameters that are processed by the boot loader are called /proc/cmdline. An example of its contents follows:

BOOT_IMAGE=/boot/vmlinuz-4.4.0-22-generic root=UUID=339228c9-cbc3-4503-950f-40415e03779f ro quiet splash

The BOOT_IMAGE parameter contains a reference to the Linux kernel and the root parameter that follows it identifies the disk drive where the boot image can be found. Note that the disk is referenced with its UUID. It can also be referenced using its device name, /dev/sda1, for example, but most modern Linux implementations will use the UUID.

How Linux Controls the Boot Process

After the kernel boots, the system will begin to initialize the user-space processes. User-space processes include starting services and daemon processes which are processes that detach themselves from the script that starts them and continue to run in the background. The way these processes get started can vary from system to system depending on how old the version of Linux is or what the Linux distribution you are using. There are two primary initialization processes:

- System V init: The traditional init process, which is called init, reads and executes a series of scripts that are located in a startup directory. Each script starts a process or service one at a time until all the scripts in the directory have been executed.

- Systemd: The newer initialization system which uses systemd-based systems initialize services and processes in parallel and can support on-demand services.

Run Levels

Run levels describe the operating mode of a Linux installation. They are mostly associated with the System V init process though the concept of run levels still exist in systemd-based implementations. At startup, the init process references its configuration file to see which run level it should use. There are seven run levels numbered from 0 to 6. Each is a directory that contains a series of scripts to start or stop processes. Generally, when a Linux system is initialized into a run level, it stays there. If you put the system into run level 0, the system halts. And run level 6 is used to re-boot the system. Typically, the lower run levels (1–2) are reserved for emergency repairs or system maintenance. The middle range of run levels are the default run levels. Run level 3 is often used to start the system with no graphical interface, and run level 5 starts the system with the graphical interface.

Each run level is a directory that contains start and stop scripts. The name of the directory includes the run level number and, in most Linux installations, you will find them in the /etc/rc directory. For example, rc.0 would be the directory name for run level 0, rc.1 would be the directory for run level 1, and so on. In each of these directories, you will see the scripts that are used to stop and start services. Scripts that begin with the letter S are startup scripts, and scripts that begin with the letter K are used to stop processes. The script names may also contain a number that determines the sequence in which to start the script relative to the other scripts in the directory.

Common Boot Management Processes

There are two boot management systems that are commonly used in Linux: System V init and systemd. To know which method the Linux host is using, do the following:

- If the system contains the directory /etc/systemd, then it is using systemd.

- If the system contains the file /etc/inittab, then it is using the System V init method

Traditional System V (init) Bootup, CentOS 6.x

System V boot or SysVinit is the traditional method for initializing user-space processes and services. Systems that use this method initialize user-space by starting a process that is called init, which controls starting the remaining user processes. It continues to run until the system is either re-booted or shut down. The init process can be called upon to change run levels if a user so desires. When init starts, it consults with a file that is called /etc/inittab to get its instructions for how to start up. One of the parameters it receives from this file is the run level that it should start in. Once the run level is determined, it executes all the start and stop scripts in that run level’s directory.

The systemd Command, CentOS 7.x

The systemd start method is a more modern mechanism for initializing user space processes and services. It is being implemented in more Linux distributions, and will soon become the standard for most Linux distributions moving forward. One of the primary benefits of systemd is that it can control other initialization behaviors such as mounting file systems. It also processes what it needs to start at initialization time in parallel, so systemd-controlled systems tend to boot faster.

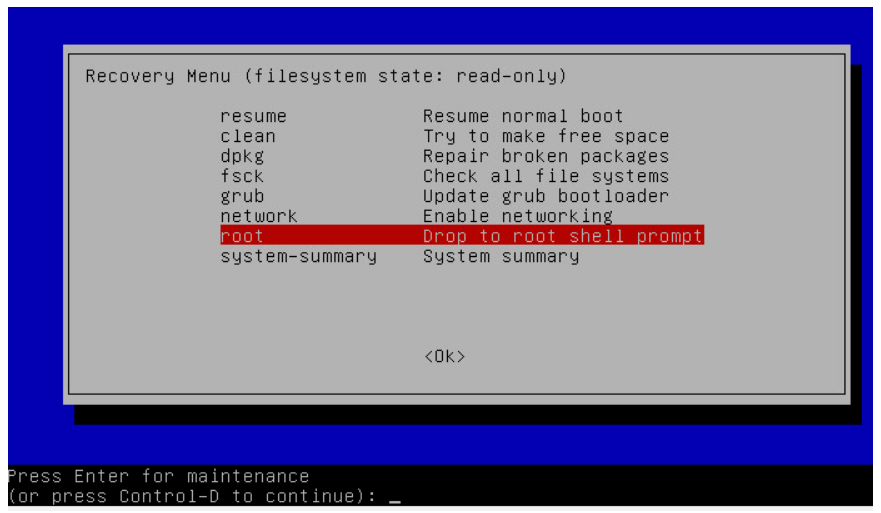

Emergency/Alternate Startup Options

If a system that is running Linux is experiencing problems or has been compromised in some way, you may want to start the system in a safe configuration, or boot the system using an external device to ensure that the system is in a clean environment.

Single User

Starting a system in single user mode is a method that is used to enter a system that may not be behaving properly. It initializes the system into run level 1, which starts only essential services and processes to allow you to enter the system to troubleshoot or test for stability. Single user mode does not start up a graphical desktop environment nor does it enable networking services. It boots into a command line console from which login and troubleshooting can be completed.

If you are concerned that an attacker may have gained control of the system, or you wish to preserve the system for forensic analysis, you should never boot into single user mode. Single user mode uses the files on disk to boot the OS and run commands. The act of booting into single user mode makes changes to critical data, like timestamps and logs, that would hinder forensic analysis.

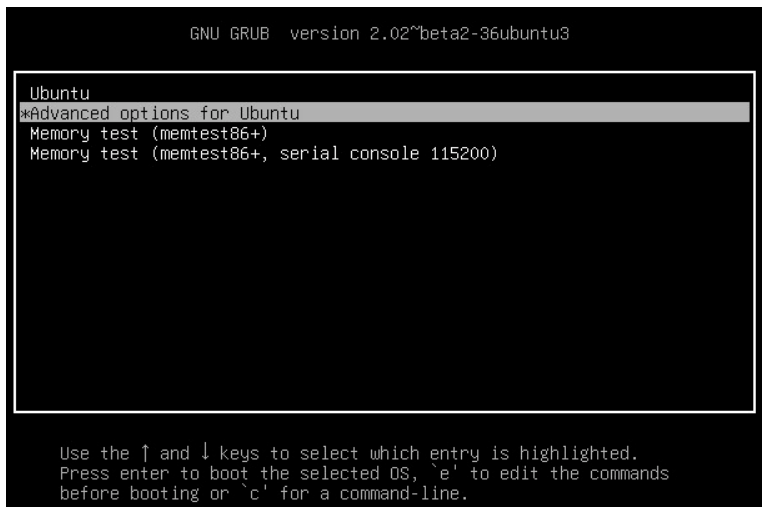

Entering single user mode may differ slightly depending upon which boot loader your system is using. Most systems use GRUB so the examples here are based on GRUB.

The steps for entering single user mode are as follows:

- First, as you boot your system, you will typically see the BIOS screen as the BIOS performs its power-on self-test and identifies the peripheral devices that are attached to the host at boot time.

- When the BIOS splash screen turns off, press the left shift key which will force the system to display the GRUB menu.

- In the GRUB menu, use the up/down arrow keys to highlight Advanced Options and press Enter.

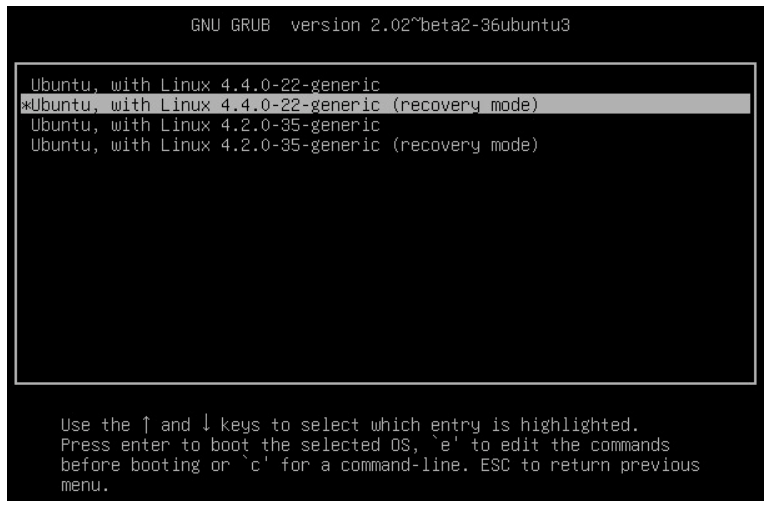

- A list of the kernels that are available to boot will be displayed. Normally, the newest kernel which will be located at the top of the list. Use the arrow keys to highlight the kernel to boot with the string (recovery mode) after it.

- With the selection highlighted, press the Enter key to get to the recovery mode menu.

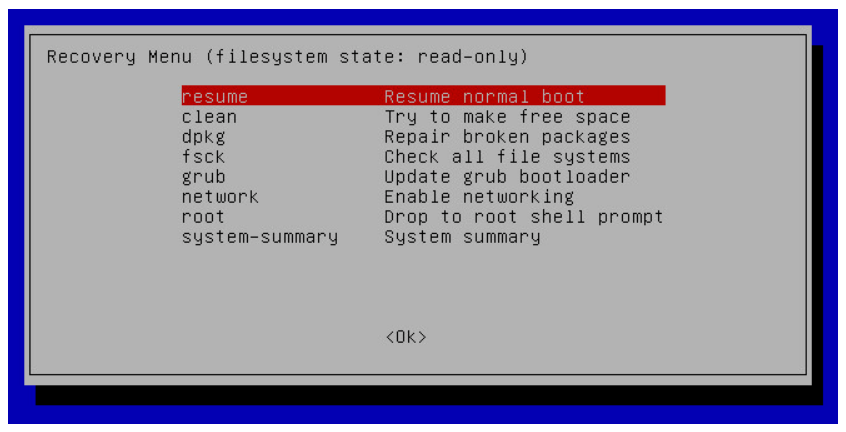

- The recovery mode screen gives you access to several tools you might find useful in an emergency situation. Of them, root brings you to a single user mode command prompt.

- From here, press Enter as prompted to execute commands for navigating the file system, or to investigate files on the host without disturbing it. The file system is mounted as read-only so you can’t alter much of it in this state. However, you can remount the file system in read-write mode if you need to make edits. Once you complete your single user mode session, you can type reboot at the prompt to restart the system. The system should restart normally at this point.

Live CD

Another option for interacting with a system that you need to analyze or troubleshoot is to boot from external media. You can obtain bootable disk images of virtually any Linux distribution. There are also many sources that provide purpose-built bootable images that come stocked with troubleshooting or security tools. These bootable distributions are known as live CDs.

Booting from a live CD is preferable in situations where the system is believed to have been compromised, or when a forensic analysis is potentially desired. Some live CDs are intended to be used in these situations, as they will not mount file systems, use files on local hard disks, or generate network traffic.

After you obtain the image file of the distribution that you wish to use, it is easy to either burn the file to optical media, such as CD or DVD, or copy the image to other storage media, such as a USB flash drive. Then, configure the host to boot from the optical disk or storage device and simply allow the system to boot. The benefit of using optical media is that the live CD can be trusted more than a USB flash drive. If you would like to be able to make changes to the live environment easily, the USB flash drive would be a better choice.

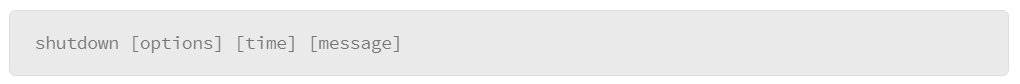

Shutting Down the System

It is important to properly shut down a Linux-based system when you need to bring the system down for maintenance or troubleshooting. Files that are not properly closed as a result of an abrupt shutdown or power loss could become corrupted causing the system to potentially malfunction. The graphical desktop environment provides tools for shutting down or restarting the system in the form of buttons in a tool bar or options in a menu.

You can also initiate a shutdown or reboot from the command line, usually done with the shutdown command. The basic syntax of the command is as follows:

There are several options that you can exercise. The two most common are –h to halt the system, and –r to reboot the system. The time argument is optional—if no time is specified, the shutdown will execute one minute after the command was issued. Time can be specified on one of two formats:

- hh:mm: The hour in 24-hour format followed by the number of minutes.

- +m: The number of minutes from the time the command was issued.

- now: The time parameter will also accept the keyword “now” to indicate that the command will execute immediately.

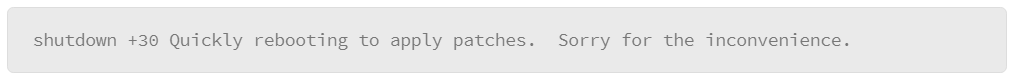

The message is also optional. It will be broadcast to all users logged in to the system, repeatedly over the course of the final minutes, to let them know the system is going down. If you include a message, you must also include a time. Five minutes before shutdown, new logins will be denied. For example, to shut down the system in 30 minutes, with a message to users:

An example of how the shutdown command can be used to halt the system is as follows:

In addition, the reboot command is a quick way to immediately reboot the system. Users will receive a broadcast message upon issuing the command:

Although the shutdown command works across every Linux distribution, systems that use systemd to manage user processes can use the systemctl command as follows:

- systemctl poweroff

- systemctl reboot

System Processes

When commands are executed, they become processes that are managed by the system to ensure that they get the memory, I/O, and CPU resources necessary for them to continue processing until execution completes or gets terminated by other means. This section describes processes, and introduces tools for monitoring them, in addition to monitoring the resources they are consuming.

Identifying the Processes

Everything that executes in the system produces a unique process that requires system resources to continue running. Processes themselves are identified by a PID to distinguish one from another. The kernel takes care of managing all the running processes to ensure they get the resources they need.

A process thread is a component of a process. It is a unit that is capable of sharing the resources that are allocated to a process. A process can consist of one or more threads. A process that is composed of one thread is called a “single-threaded process,” and a process that contains more than one thread is called a “multi-threaded process.”

Multi-threaded processes have the advantage of being able to run in parallel, which can increase the speed at which a process runs. Multi-threaded processes always start as a single thread, which is known as the main thread, which will spawn additional threads as needed. Threads have their own unique identifiers, called TIDs, which allows the kernel to track them, much like the kernel would track processes by PID.

Linux Process Creation

New processes are created in Linux with a fork-and-exec mechanism. When a process makes a fork call, a new process with a new PID is created. The process that made the fork call is the parent process and the new process is the child process. The child process starts as a duplicate of the parent process, with some significant status changes. Both processes receive a value from the fork call. The parent process receives the PID of the child process while the child process receives the value 0. The two processes can determine which is which by the return value of the fork call.

Most commonly, the child process will then make an exec call. The exec call facilitates replacing a process with an entirely new program. As an example, the Linux CLI is made available to the user by a shell process. The shell process monitors standard input. When the user enters a command via standard input, the shell parses the command. If the user input matches an available executable file, the shell process will make a fork system call. This creates a new shell process as a child to the parent shell process. The child shell process then immediately makes an exec call, replacing itself with the program defined in the user specified executable file.

The fork call is not always followed by an exec call. A program may contain the code for both the parent and the child process. For example, a daemon that listens on a TCP port may fork a child copy of itself when a new connection is initiated. The child process handles the all aspects of that TCP connection. The parent process can fork multiple copies of itself to handle concurrent TCP connections.

Monitoring Running Processes

The ability to monitor processes and determine the resources that they are using is critical if you do any level of investigation on a host. This topic describes several tools that allow you to view running processes and process threads. It will also present tools built into Linux to show you the resources being consumed by the processes running on the system you are investigating.

Displaying Processes and Process Threads

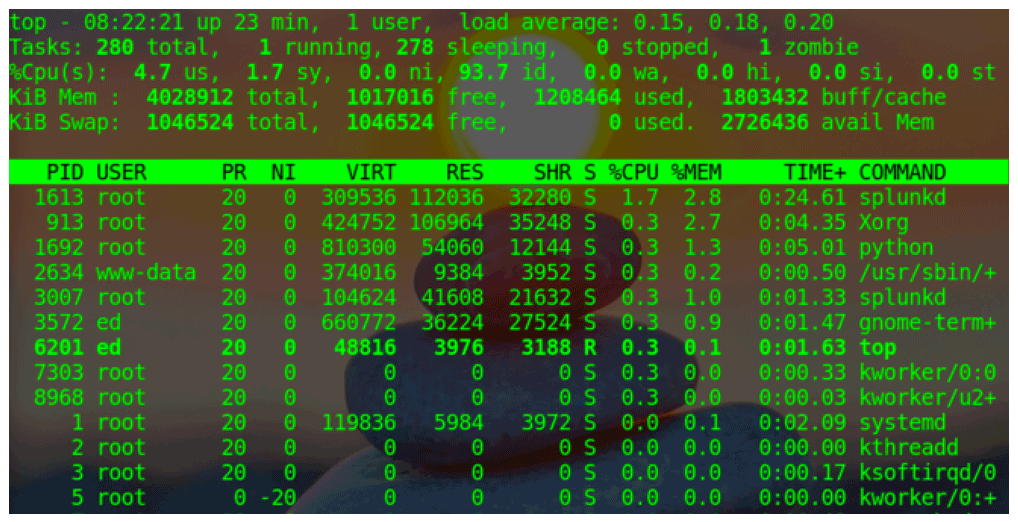

One tool that you can use to view running processes is called top. This tool remains open giving you a real-time view of system information including system up time, process information, and resource utilization. Exit top by pressing the letter q or <Ctrl+C>

The top application screen is divided into two sections. The upper portion lists general information regarding system resource utilization as follows:

- The first row lists system up time and system load average. The load average is represented as three decimal numbers which, from left to right, show the load on the CPU over the last 1, 5, and 15 minutes.

- The second row gives you general information about the processes running on the host.

- The third row lists various aspects of how the CPU is being utilized. Some of the statistics you may find useful at a glance include the following:

- us: user space processes

- sy: system/kernel processes

- id: system idle time

- The remaining rows provide information on how memory and swap space is being utilized. The first of the two rows shows system memory utilization and the second is for swap utilization.

The lower section shows details of the top running processes. The larger your terminal window, the more processes top can display. Each row in the lower section represents a process. The top application’s screen refreshes approximately once a second. So the values displayed and the position a process occupies will shift with each refresh as it represents the state of the system at the time of the refresh.

The columns of information that is displayed by top are as follows:

- PID: Process ID number. When a process is started, it is given a unique PID that identifies that process to the system. If you ever need to kill a process, you can refer to the process by its PID.

- User: The user name of the process’s owner

- PR: The scheduling priority of the process

- NI: The process’s nice value.

- VIRT: Virtual memory

- RES: Resident, non-swapped physical memory

- SHR: Shared memory

- S: Process status

- D: Uninterruptible sleep (stuck waiting for input or output)

- R: Running (executing normally)

- S: Sleeping (waiting internally)

- T: Stopped by job control (stopped with a signal from the kernel)

- t: Stopped by debugger (another process has full control)

- Z: Zombie (completed processes that are not yet removed from the kernel's process table) - %CPU: The estimated percentage of CPU resources being consumed by the process

- %MEM: The percentage of physical memory being consumed by the process

- TIME+/–: The total CPU time the process has consumed since it started

- COMMAND: The name of the process

Be advised that there are many more features available in top. These features are seen by default. However, there is a lot of information it provides and it is in real time as long as top continues to run.

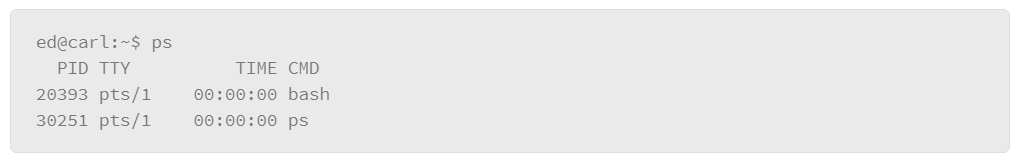

The ps Command

To extract more specific information about processes, you can use the ps command. This command has an extensive list of options that you can use to get information about processes. This section will cover some examples of what you can do with the ps command.

There are several ways to express options to the ps command, as follows:

- UNIX: Options can be grouped and must be preceded by a dash.

- BSD: Options can be grouped and must not be preceded by a dash.

- GNU: Long form where options are preceded by double dashes.

Because of this flexibility, it is possible to achieve the same result with the ps command several different ways. The methods can be mixed, but may conflict. If your output is not what you expect, it may be the result of a conflict.

By default, the ps command only lists processes that are associated with the user running the command. You can override this behavior with options to specify processes that are owned by specific users or all users.

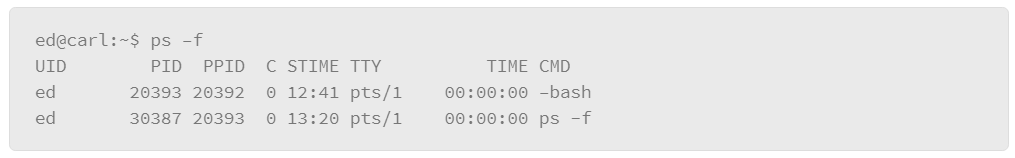

An example of using the ps command in its simplest form is as follows:

</li>

</li>

The example output above shows the processes that are owned by the user who executed the command. For each process, it shows the PID, the terminal that the process is running in, the CPU time that is being consumed by the process, and the name of the command.

To add more information about the processes that are returned by the command, add the –f option, which gives you full output.

Using the -f option added the following columns:

- UID: User ID of the owner of the process

- PPID: Parent Process ID. In addition to a unique process ID, each process is assigned a parent process ID (PPID) that tells which process started it. The PPID is the PID of the process’s parent. The init process (PID 1) is the parent of all processes without a parent process.

- C: CPU utilization percentage

- STIME: Process start time

To see the processes for all users, you can add the –e option. If you combine the –e and –f options, you get both the full set of columns and processes for all users. You can shorten the options by grouping them after the dash (-ef). An example in the command line is:

This example is using the UNIX style syntax for expressing options. The equivalent command using the BSD style would appear as follows:

Notice the absence of the dash. Also, this style includes a few more columns to correspond with BSD style output.

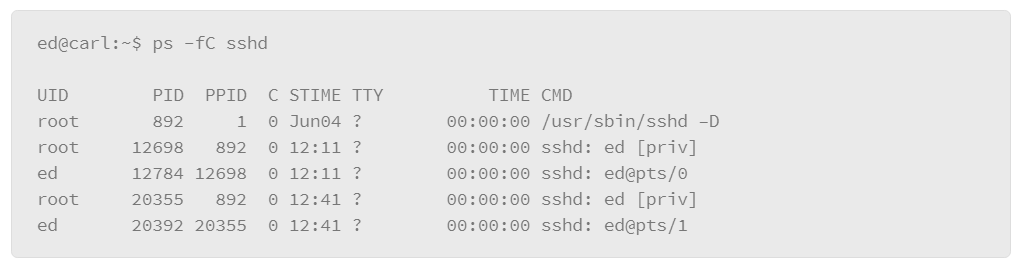

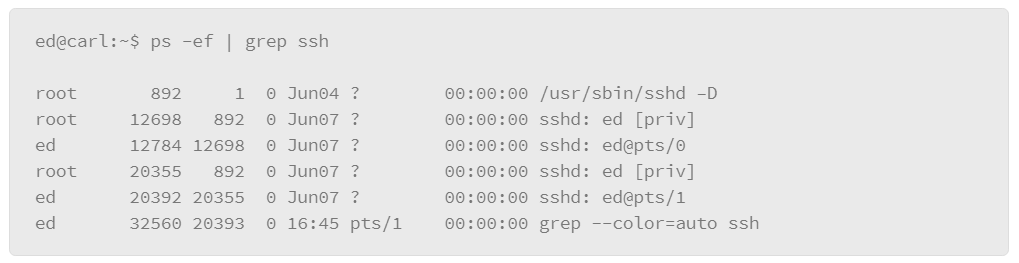

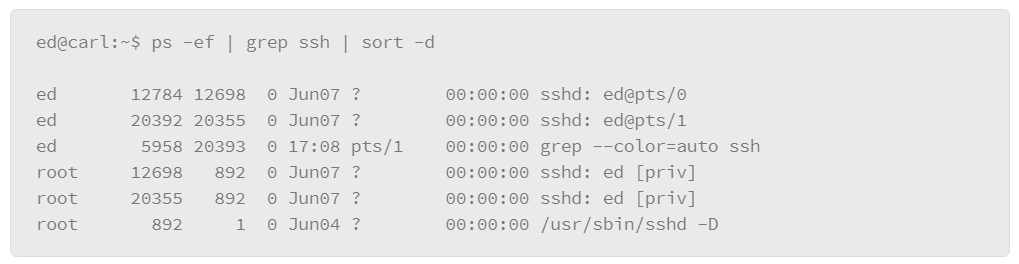

The output that either of these examples produces is rather lengthy, because essentially it lists all the processes for all users. However, you can filter the listing several ways. The first method is to include the –C option (upper case), followed by the name of the process you are interested in. For example, to list the processes that are associated with the SSH server, do the following:

In the example, the –C option is grouped with the –f option, which produces the full output style, and filters the output to the processes that relate to the SSH service called “sshd.”

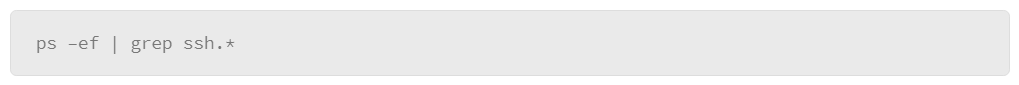

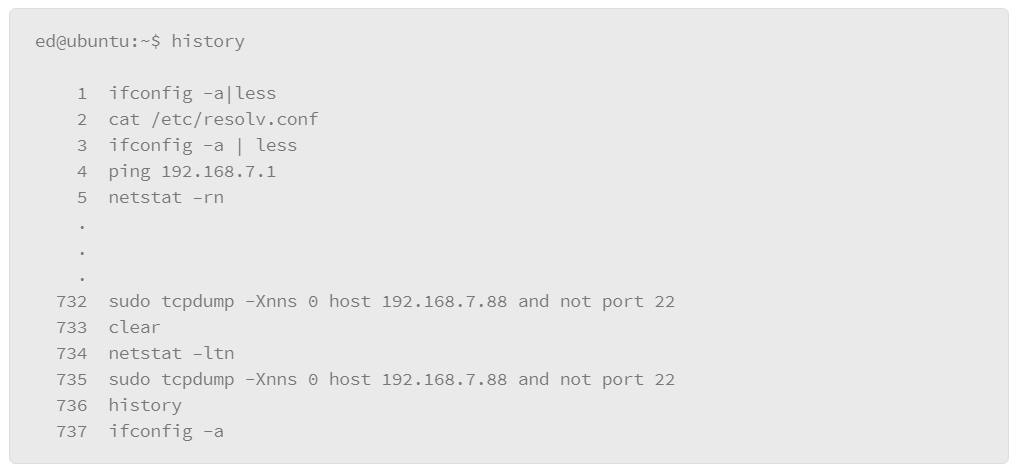

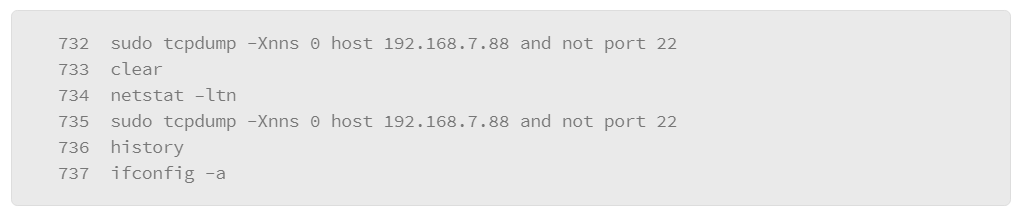

The disadvantage of this method is that it assumes that you know the precise name of the process that you are interested in. For more flexibility, you can pipe the output of the ps command to a grep filter. “grep” is a Linux command that you can use for filtering with wild card characters or regular expressions. The basic format of this usage is to pipe the output of the ps command to the grep command, where you can express the filter that you wish to apply, as in the following example:

In the example, -e lists every process and -f displays the output in the full format. Next is the vertical bar or pipe character, which passes the output of the ps command to the grep command, which contains the filter that you wish to apply. In the example, the filter is ssh.* which is expressed using a regular expression-style wildcard. The .* option means “any,” so it will match on any line of output from the ps command that contains the string ssh followed by any characters.

Displaying Open Files

Another tool that is useful when analyzing or troubleshooting a Linux-based system is to list the files that are currently open in the system, which includes files that a user may have open or files that a process may have open. Since Linux tends to treat everything as if it is a file, including devices, you will also be able to list things such as device file references, directories, and even network connections.

The primary tool for this purpose is the lsof command. This command contains an extensive list of options and it is common to most of the Unix and Unix-like operating systems. Therefore, some of the options may only work in certain environments. Also, the amount of information output from the lsof command can be extensive, so learning how to filter its output makes using it more useful.

In its most basic usage, the lsof command lists every open file. The amount of output could be overwhelming unless you are more specific about what to look for by applying options that target specific types of files or by file ownership.

This example of lsof usage can be used to list the processes accessing a specific file. For example, if you want to know which processes are using the syslog file, you can apply the following command:

Some of the key features of this output include the following:

- Command: The name of the process using the file.

- PID: The process ID of the command using the file.

- User: The user running the process.

- FD: File descriptor: a reference number that is used by the kernel to identify an open file. File descriptors may be followed by a code letter to further describe the state of the file. In the example, the letter “w” indicates that the process has a write block on a portion of the file.

- Type: Identifies the type of file. For example, DIR represents a directory, inet is a network connection or BLK to represent a block device such as a disk drive. The example lists the type as REG which represents a regular file.

- Device: Device number that represents the device being called to perform the I/O.

- Size/Off: The file size or memory offset. The lsof command will display whichever one is appropriate for the file being listed.

- Node: The file’s INODE number, which is used to uniquely identify the file on the file system.

- Name: The path and file name

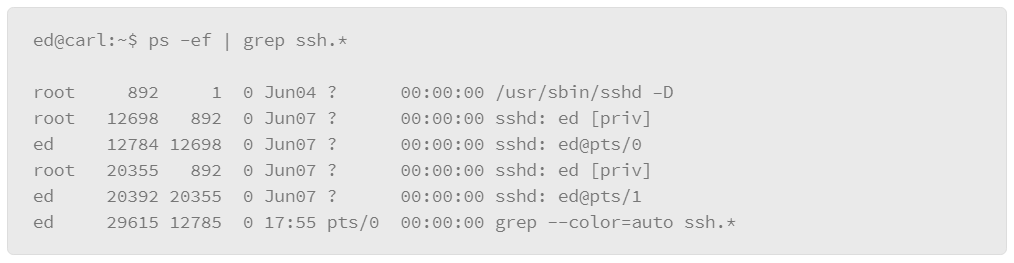

To list the processes that are accessing log files in a directory, you can use the +D option:

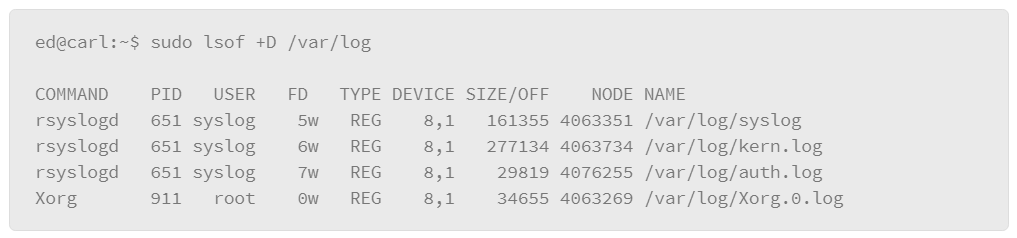

To find the files that a particular process has opened, you can use the –p option with the lsof command, which lets you specify a PID number as follows:

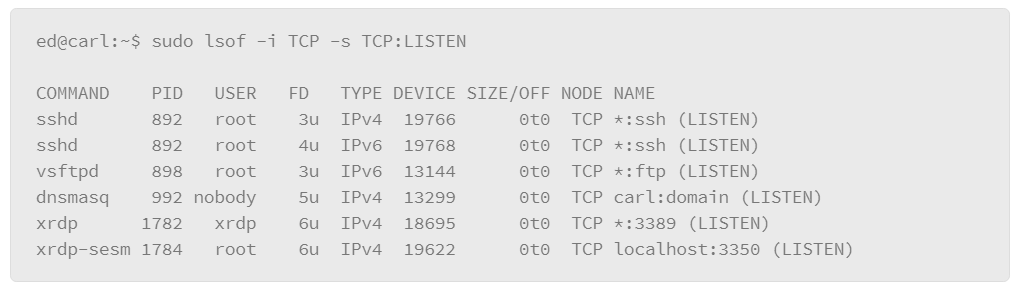

The lsof command can also be useful for tracking the state of network connections. For example, you can view the services that are listening for connections with the following command:

In this example, the output lists the commands for all the TCP services that are listening for connections, which is useful for determining if strange or unauthorized services are running on the host. The –i option is used to specify the network characteristics to output. Here, TCP filtered the output on only TCP-based services. The –s option lets you specify a protocol and the the protocol state that you want to output, where the protocol and state are separated by a colon (:). In the output, you can see the command and, at the end of each line, the host:service followed by the state: LISTEN.

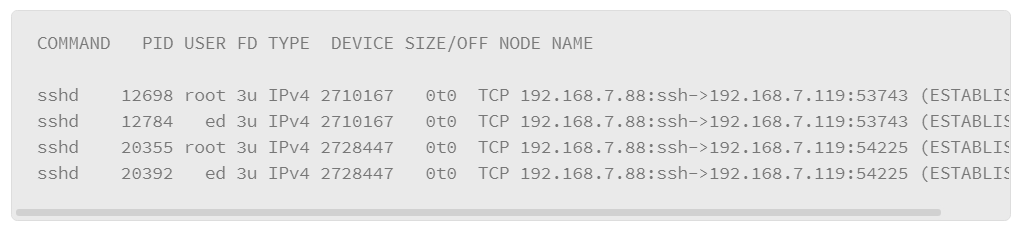

A variation of this command allows you to show services with established connections as follows:

One of the key pieces of information that is produced by this implementation of the lsof command is that it shows the IP addresses and port numbers that are used by the hosts that have established connections.

Monitoring CPU and Memory Utilization

Monitoring system resource consumption can be a critical part of investigating a host. Excess resource consumption can be the result of many things and often it is symptomatic of an attack. For example, the compromised host may be sending out spam emails, or it may be the victim of a DoS attack.

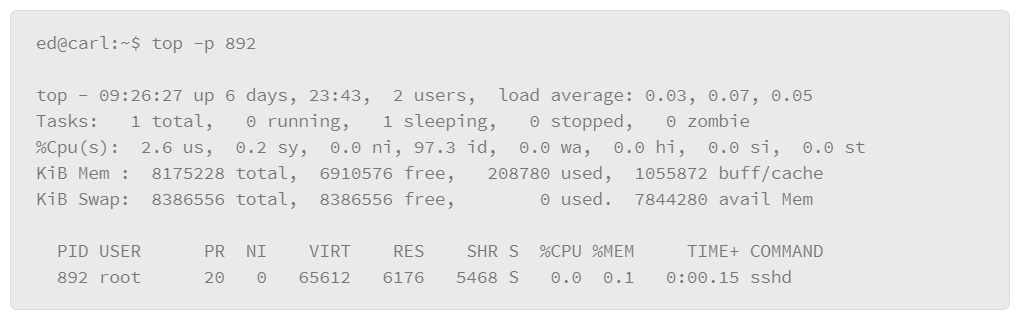

The top command provides a lot of information regarding resource utilization in real time. The top command also lets you select specific processes to monitor, so you can gauge the resources that are consumed by that process. For example, you can add the –p parameter to specify the PID that you wish to monitor as follows:

As you can see in the example, it produces the same output as the top command, except the process detail portion of the output is filtered down to the process that you specified in the command.

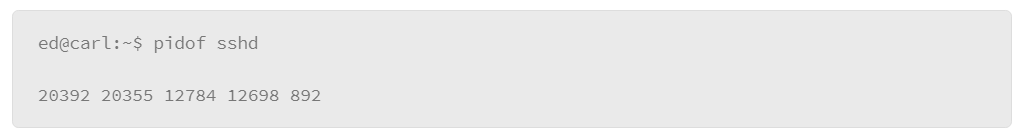

If you are not sure which PID you are interested in, you can find it with the pidof command, as follows:

In this example, the PID of the SSH service, sshd, returned five PIDs, which indicates that there are five instances of this process running on the host.

There are other tools to monitor resource utilization. Memory is an important resource so you may want to track how it is being utilized. One concern regarding memory is the impact that it has on the system when memory resources run low. Linux uses disk space as an extension of real memory by reaching out to the swap partition of the file system. The more the system has to reach out to the swap partition, the greater the impact on the system’s performance. Therefore, you may wish to monitor the processes that are reaching out to the swap space.

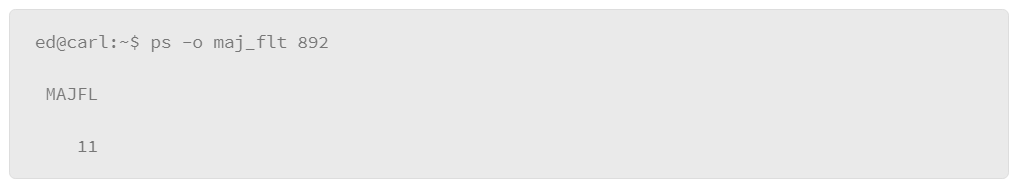

The ps command provides options that allow you to do just that. The –o option to the ps command lets you specify information that you want about a process, rather than outputting the standard set of information that it normally produces. In this example, request the number of major page faults with the maj_flt parameter in the –o option, as follows:

A major page fault happens when a process requests memory resources from the system and those resources are not available at the time of the request, which causes the system to reach out to the swap space so that it can get the resources that it needs. Page faults are not particularly unusual, but large numbers of them can be an indication of an under-resourced system, or a process behaving strangely. In the example, the process returned 11 major page faults, which may not be unusual for a long-running process.

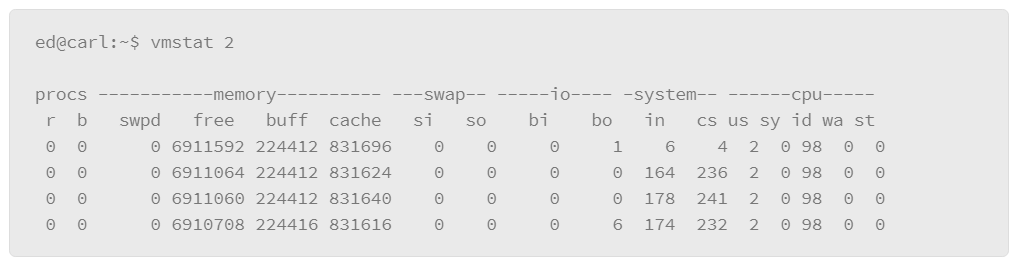

For a broader view of memory utilization relative to swap activity, you can use the vmstat command. This command is similar to top, if a time parameter is added, it continues to run and produces output on the interval of time that is specified in seconds. In this example, run vmstat with a time parameter of 2 to indicate retrieval of current memory statistics every two seconds.

To exit the command, press <Ctrl+C>. This command produces a lot of output, the most relevant pieces should be the focus. The top row organizes the output into categories of information, and the second row outlines what each column represents regarding the category that it falls under. The categories are as follows:

- procs: Lists the number of processes in either a runnable state (r) or in uninterruptible sleep (b).

- memory

- swpd: Virtual memory used

- free: Available memory

- buff: The amount of memory that the kernel is using for buffering

- cache: The amount of memory that is reserved as cache - swap

- si: Swapped in

- so: Swapped out - io

- bi: Blocks that are received from block device

- bo: Blocks that are sent to block device - system

- in: Number of interrupts

- cs: Number of context switches - cpu

- us: CPU time spent processing non-kernel (user) processes

- sy: CPU time spent processing kernel processes

- id: CPU idle time

- wa: Time spent waiting for I/O

- st: Time that is stolen from virtual machine

Regarding swap usage in the example, the system has not used any, and there is a lot of available memory. Given the values in the remaining segments of the output, you can see that this system was not very busy at the time that the command was run.

Monitoring I/O

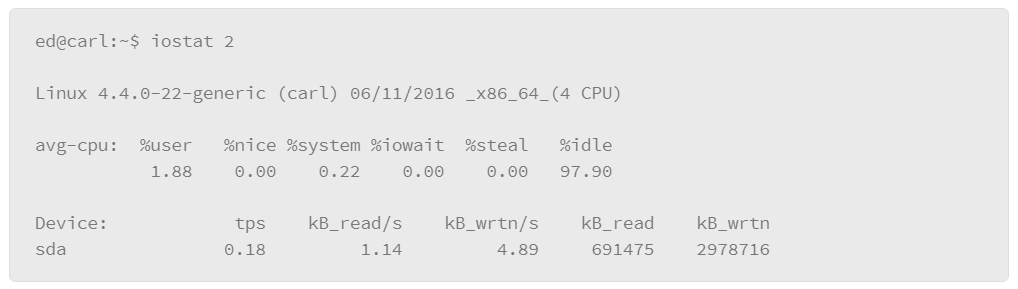

Another aspect of the system that you may wish to monitor is general I/O. A good tool to give you an idea of the amount of I/O taking place on a system is the iostat command. The iostat command is similar to vmstat in that you can pass it a time delay parameter in seconds or you can use it without the time delay to get a snapshot of current I/O activity. The following is an example of this command:

The upper portion of the output shows general CPU utilization statistics. The lower portion of the output lists the devices that are producing I/O and statistics that are related to the amount of I/O the device is producing. The tps column represents transfers per second. The remaining information simply displays reads and writes per second, and the amount of data that are read and written to the device.

Interacting with Linux

Linux Command Shell Concepts

The command shell in Linux provides a powerful environment for interacting with the operating system.

Environment Variables and Shell Variables

Linux provides mechanisms for creating variables that represent text strings you can access with the variable name rather than the string itself. A common use case for this functionality is to store file system locations that you can reference with the variable. In fact, one of the more important variables that you will encounter frequently as you interact with the shell is a variable that is called $PATH. This variable stores a list of the directories that the system searches when you execute a command.

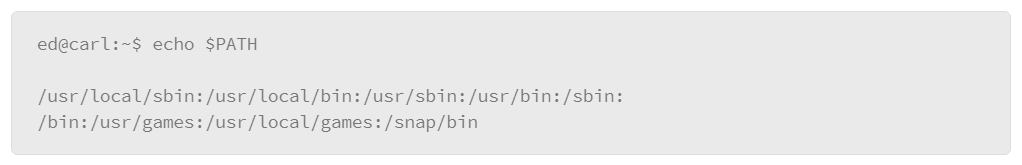

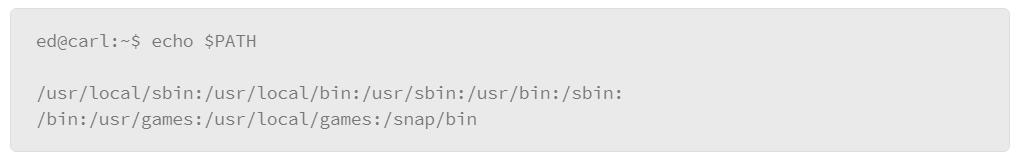

To see the value that is associated with the $PATH variable, issue the following command:

The echo command prints some value to the screen. In this example, the value is the $PATH variable. The output that it produces is a colon (:) separated list of directories that are the locations searched for commands you wish to execute. If a command that you intend to execute is not in one of these directories, you must provide the path to the command when you execute it.

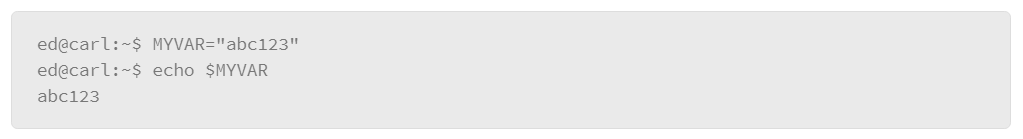

$PATH is an environment variable. Environment variables are available system wide. You can view all of the environment variables using the env command. Shell variables are only available in the current shell. You can create shell variables at any time as follows:

In the example, a shell variable named MYVAR is created and assigned the value abc123. Then, the echo command displays the value of the variable. You can see that it produced the text abc123, which corresponds to the value assigned to the variable. Note that when the variable is created, the name is specified to assign to the variable. When the variable is used, prepend the dollar sign symbol ($) to it as follows: $MYVAR.

$MYVAR is not available to other shells running on the same Linux system. It is only available to the shell under which it was defined. Shell variables can be made available to other shells, as environment variables, using the export command.

Creating variables is most often used in creating shell scripts, which are essentially sequences of commands that you can package into a text file and execute as if it were a command. As it pertains to normal interaction with the shell, it is important to know of the existence of variables. In particular, the $PATH variable is important to know because that will often determine how the shell goes about finding a command that you wish to execute.

General Command Structure

In general, when you execute system commands, you simply provide the name of the command at the shell prompt followed by any options that you wish to include with the command. System commands will normally reside in one of the directories that are specified in $PATH, so the shell should have no problems finding the command, unless you misspelled it.

Sometimes, you may want to build applications from its source code, or you may have downloaded an application that is already compiled. Then, when you attempt to execute the application from the command line, you may find that the system does not recognize the command, which can be particularly puzzling if you are in the directory the application resides in.

The reason may relate to the $PATH variable. If the command to start the application is not in $PATH, the system won’t find it, even if you are in the same directory as the command. To execute a command that is not in $PATH, you must provide the fully qualified path to the command when you execute it.

In situations where the location is the same directory as the command to execute, provide the self-referential directory path instead. The Linux file system contains two special directory references:

- . (single dot): Represents the current directory which is also known as a self-referential directory.

- .. (double dot): Represents the parent directory or the directory that is one level up from the current directory.

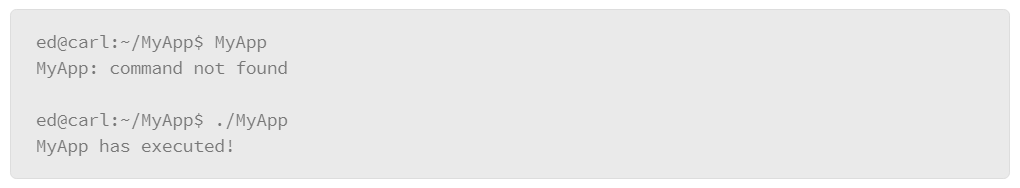

Therefore, if you downloaded the source code for an application into your home directory, and, after compiling it, you wish to execute it, you must include the self-referential directory in the command or the system will not find it, even though you are in the same directory, which is true because home directories are not in $PATH.

Consider the following example:

In the first attempt to run the command, the system reported that it could not find the command. In the second attempt, the self-referential directory followed by the slash to specify a path of the current directory. In this instance, the command executed successfully.

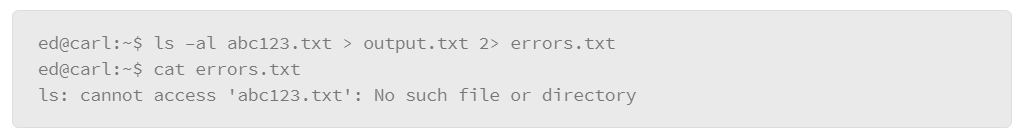

STDIN, STDOUT, and STDERR

An important concept behind the Linux shell is that Linux treats input to commands and output from commands as streams of data which also holds true for output that is produced by errors. The following structures define these streams:

- STDIN (0): Standard input which normally comes from your keyboard but can also come from a file

- STDOUT (1): Standard output which is normally directed to the display, but it can be directed to files, processes or directly to other devices

- STDERR (2): Standard error is usually reserved for output that is produced by error messages. Like STDOUT, it normally goes to the display but can be directed to other destinations such as files or devices. STDERR is typically used for debugging or troubleshooting.

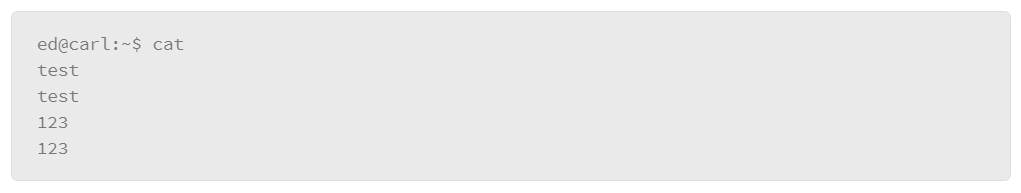

To test STDIN, you can use the cat command. The cat command is used to display the contents of the file you specify as a parameter to the command. It dumps the contents of the file to STDOUT, which is the screen if you don’t direct the output elsewhere. If you don’t specify a file as the input source, the cat command takes its input from the default input device which is the keyboard. In this example, STDIN represents what you type at the keyboard:

In the example, the cat command is executed with no options. Then, the string test, and when the Enter key was pressed, the cat command sent the string that was entered into STDIN, to STDOUT. The process was repeated with the string 123.

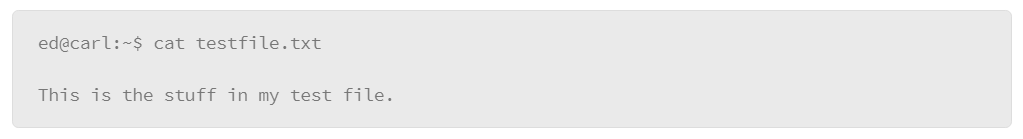

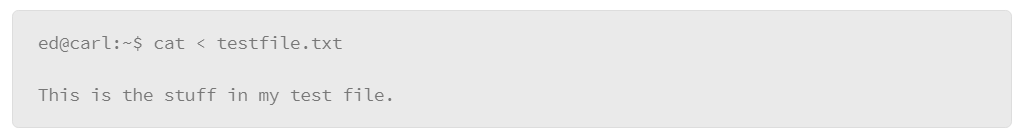

Most commands like cat take a file as input. For example, to display the contents of a file that is called testfile.txt, issue the following command:

However, direct the contents of the file to the “cat” command using the STDIN directional operator, the less-than symbol, as follows:

Note that the command produces the same output. The only difference is that, instead of specifying the file as an option, the directional operator to direct the contents of the file to the command as its input source to demonstrate how to direct input to a command.

A command’s output can be directed. Use the echo command to demonstrate this functionality. The echo command normally echoes, or copies, the value specified as the command option to the screen. For example, echo the value of the $PATH environment variable to the screen, as follows:

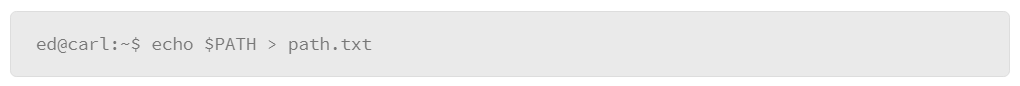

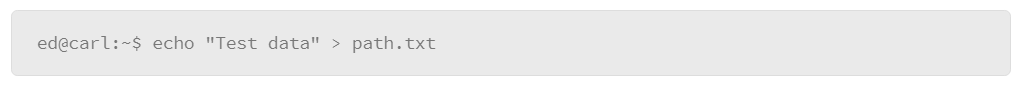

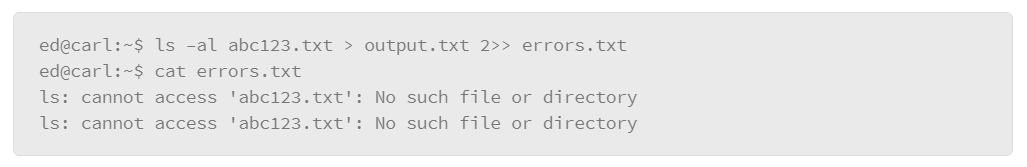

However, rather than directing this output to the screen the way the echo command would normally work, you can direct the STDOUT to a file instead, using the greater-than symbol as follows:

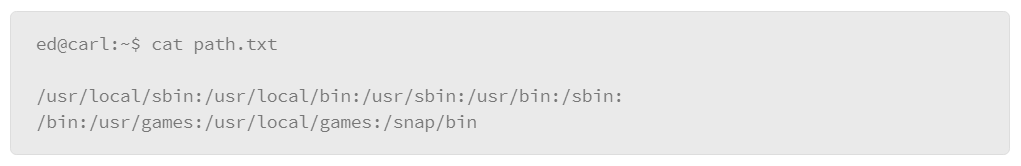

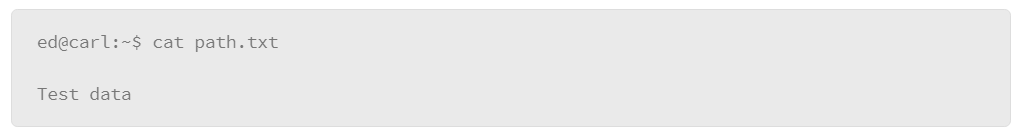

Note that the command does not produce output to the screen. However, it did create a file that is called path.txt, in which the output that would normally be directed to the screen is placed, which is an example of changing or directing STDOUT to a file. To test, use the cat command to view the contents of the path.txt file, as follows:

The path.txt file contains the output from the echo $PATH command. One thing to note is that it is easy to overwrite this file. For example, issue the following command:

It writes over the path.txt file with the data that you specified in the echo command, as follows:

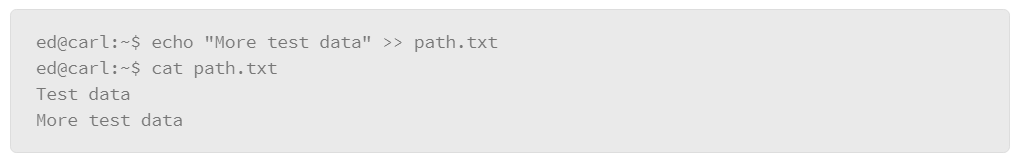

The previous data in path.txt was completely written over with no warning. This process is known as clobbering the file. However, you can use a variation of directing data through STDOUT to append, rather than overwrite, using the following syntax:

The example shows two consecutive greater-than symbols to append data to a file rather than overwriting the file which used the echo command to send another string of text to the file, and the operator appends the data. Then the result was tested with the cat command. The path.txt file now contains two lines: the original line of text (Test data) and the appended line (More test data).