Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 8: Understanding Windows Operating System Basics

8.2 Windows Operating System History

8.3 Windows Operating System Architecture

8.4 Windows Processes, Threads, and Handles

8.5 Windows Virtual Memory Address Space

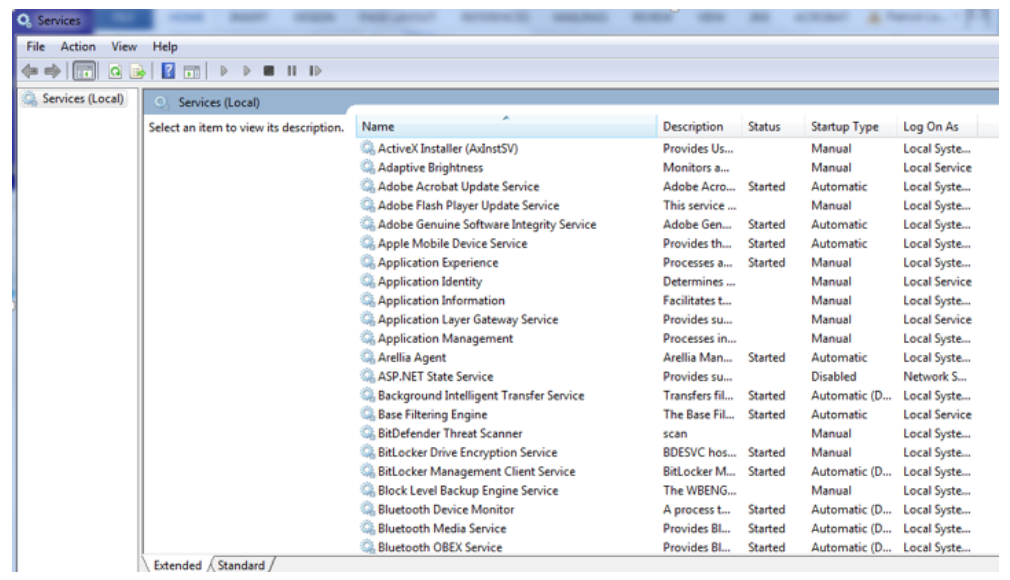

8.6 Windows Services

8.7 Windows File System Overview

8.8 Windows File System Structure

8.9 Windows Domains and Local User Accounts

8.10 Windows Graphical User Interface

8.11 Run as Administrator

8.12 Windows Command Line Interface

8.13 Windows PowerShell

8.14 Windows net Command

8.15 Controlling Startup Services and Executing System Shutdown

8.16 Controlling Services and Processes

8.17 Monitoring System Resources

8.18 Windows Boot Process

8.19 Windows Networking

8.20 Windows netstat Command

8.21 Accessing Network Resources with Windows

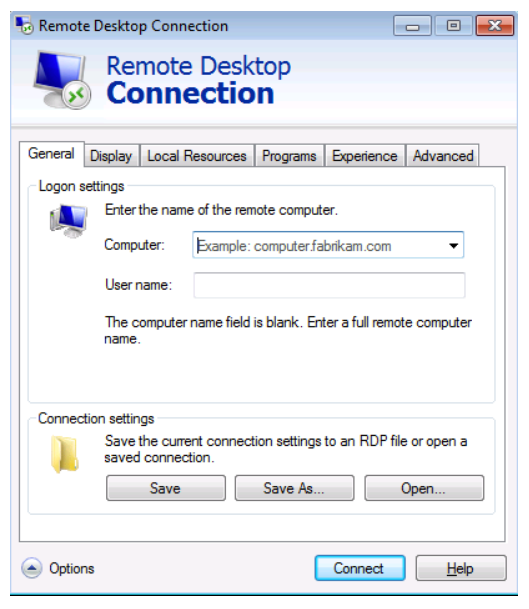

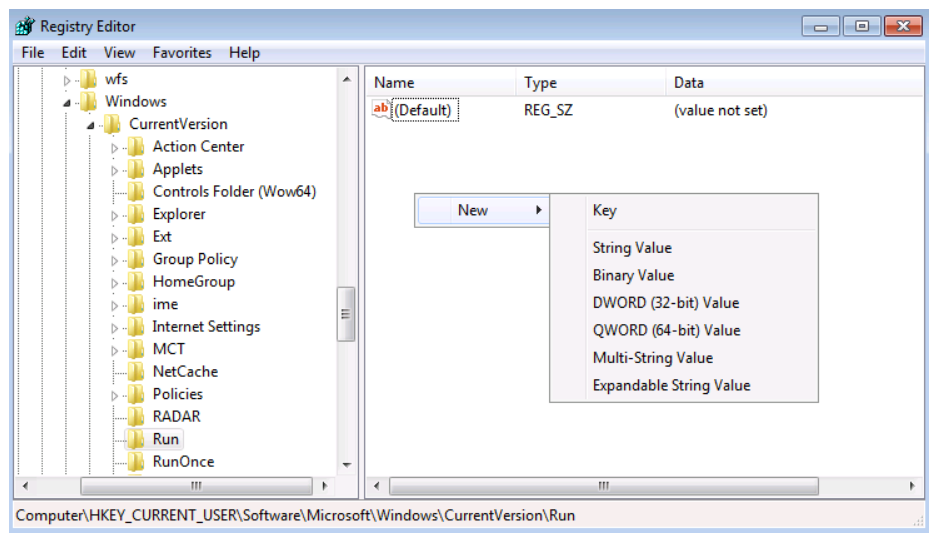

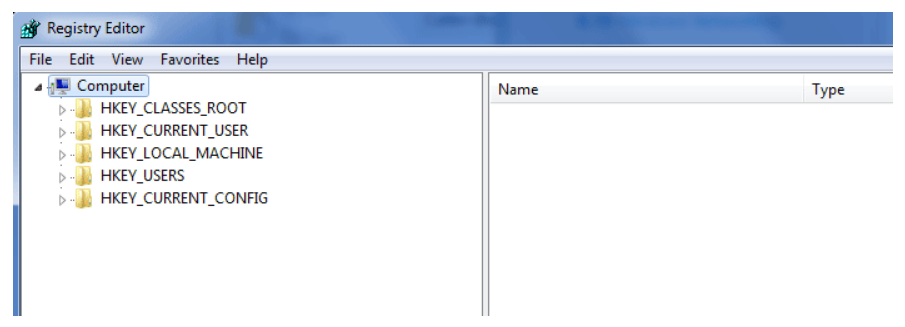

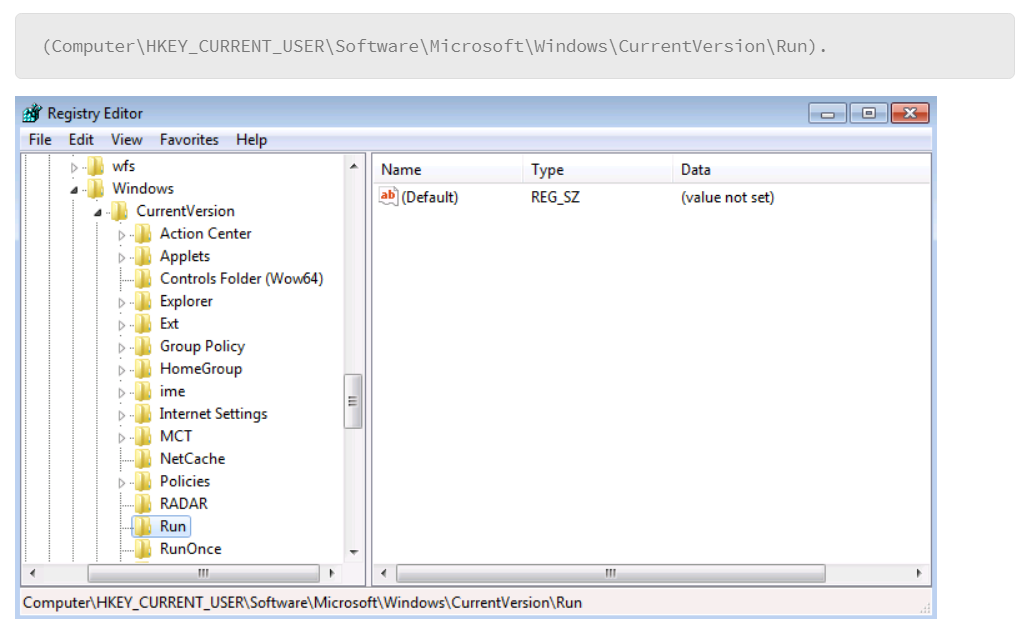

8.22 Windows Registry

8.23 Windows Event Logs

8.24 Windows Management Instrumentation

8.25 Common Windows Server Functions

8.26 Common Third-Party Tools

Windows Operating System History

Microsoft Windows has been a family of operating systems for personal computers since 1985. In addition to Windows OS for personal computers, Microsoft offers operating systems for servers and personal mobile devices. Originally developed by Microsoft for IBM, MS-DOS was the standard operating system for IBM-compatible personal computers. The latest Windows OS is Windows 10 (the successor to Windows 8), which debuted on July 29, 2015.

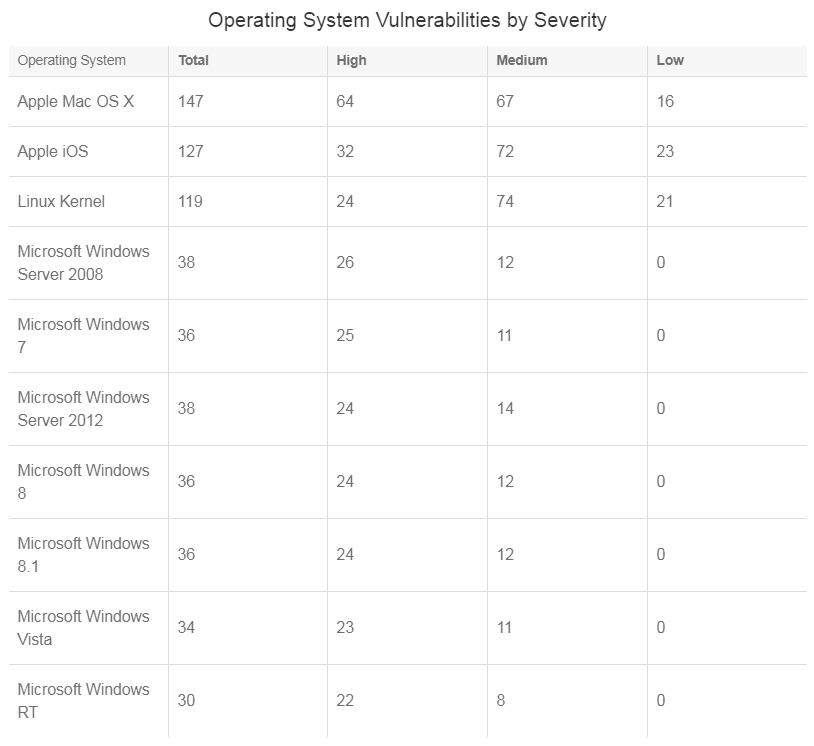

It is interesting to note that although Microsoft operating systems have several vulnerabilities, they are not in the top three, as reported in the 2014 NIST National Vulnerability Database, as shown below.

Note:

Go to https://nvd.nist.gov/ to view the National Vulnerability Database on NIST's web site.

Windows Operating System Architecture

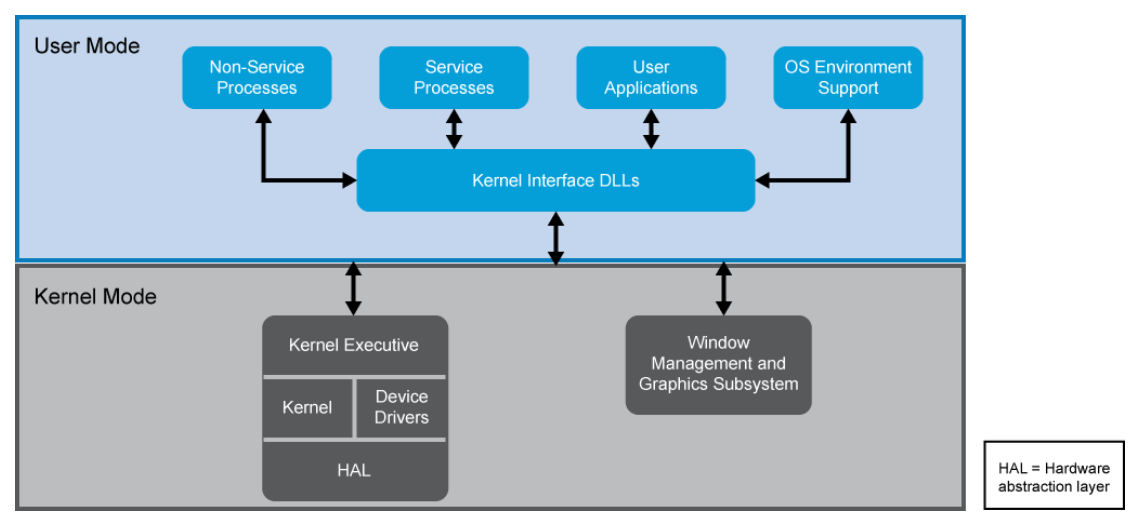

The Windows OS has evolved into a robust enterprise computing platform that ranges in use from everyday end user desktop environments to data center-scale server platforms. Its architecture has matured to include features that provide system stability and security. Although Windows is used most often as a desktop computing platform, its server platforms are used extensively in corporate data centers by IT professionals. The operating system’s architecture is common across all its offerings and consists of two major components:

- User mode: This component manages processes on behalf of system users. It runs with lower privilege so users can’t directly interfere with system level processes. It also provides communication pathways that are known as APIs so that user processes can request access to system level resources.

- Kernel mode: This is where the core processes of the operating system run. Its processes run with the highest level of privilege so it can manage system CPU and memory resources.

The figure illustrates the various architectural components of the Windows OS, and outlines major processes that each component handles.

This is not an exhaustive list of all the elements for each component, but it does outline the major processes and which mode is responsible for each. One of the concepts of the Windows architecture is how processes are treated relative to the mode in which they reside. For example, the user processes appear to occupy their own distinct spaces, which roughly equate to the memory resources the operating system dedicates to each. By design, this prevents a user mode process from accessing the memory space of another process. This mechanism enhances the security and stability of the system.

Kernel mode processes also operate within the same memory space. However, kernel mode processes are higher privileged functions that cannot be directly accessed by lower privileged user mode processes. Executing processes in the same memory space increases the overall efficiency of the system.

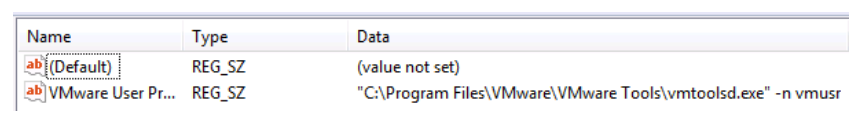

User mode and kernel mode processes are the Windows subsystems that form the core of the operating system. They are started at system initialization by the Session Manager (Smss.exe). The following registry key will identify the system’s operating mode HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Session Manager\SubSystems.

User Mode

User mode processes are specific processes initiated or owned by Windows users. These processes operate within the confines of their own memory space or spaces. This prevents one user’s process from accessing another user’s process space or resources. The system does provide mechanisms for one user process to request resources from another. This is handled through specific API calls that are tightly controlled by the system, which prevents a process from arbitrarily impinging on another user’s process space while reducing the potential of system corruption. Remember, user mode processes operate at lower system privileges than kernel mode processes to maintain the separation between the user and kernel mode spaces.

The types of processes that run in user mode can fall into one of four general categories:

- Non-service processes: These are fixed processes that support user access to system resources such as logon services and Session Manager. These are not services in a strict sense because they are initiated by user activity and not started by the service control manager.

- Service processes: These are services that run in support of user system requirements; they are not system services that run independent of users, and are generally initiated by the system through the service control manager. Some examples include the Task Scheduler and Print Spooler.

- User applications: As the name implies, these are the processes that are needed to run applications that are initiated by users.

- OS environment support: Windows NT originally shipped with support for Windows, OS/2, and POSIX subsystems to support a Windows design goal of code portability. Recent versions of Windows have dropped support for OS/2 and POSIX in favor of an enhanced version of POSIX that is called Subsystem for UNIX-based Applications (SUA). The OS environment support subsystem manages the subsystem components to use based on what is required by running applications.

User mode applications and services often need to utilize resources that are managed by kernel mode processes. For example, a user mode process may need to write to a file or initiate a network connection. To support user application requirements, Windows can allow a process to switch contexts from user to kernel mode. When the operation requiring the system level resource completes, the system will switch the context back to user mode. This function is handled by a kernel interface layer that manages context switches and will prevent user mode processes direct access to system level resources.

Kernel Mode

A large portion of the Windows OS runs as kernel mode processes. Unlike user mode processes, where each process runs in its own protected memory space, kernel mode processes share the same memory space. This provides speed and efficiency, along with the opportunity for a misbehaving process to potentially impact the entire system. To mitigate this possibility, Windows enforces kernel mode code signing, which means that drivers and critical system files must be signed by a cryptographic key from a public certification authority.

Major processes that run in kernel mode include the following:

- Kernel executive: Performs base operating system services such as I/O, networking, and memory management

- Kernel: Responsible for managing low level system operations such as thread scheduling and managing system interrupts

- Device drivers: Handles the requests for I/O to and from connected hardware devices

- Hardware abstraction layer: HAL is a layer of OS code that handles interaction between the kernel and hardware to account for differences between platforms such as motherboards. This allows the OS to be insulated from the hardware so that the OS itself does not need to adapt to hardware differences. Rather, the HAL handles low level hardware contingencies by translating them to standard OS functions.

- Window management and graphics subsystem: Implements the GUI and manages graphic functions for Window management and interface controls

- Ntoskrnl.exe: Windows executive and kernel

- Hal.dll: HAL module

- Win32k.sys: Kernel-mode device driver for managing Windows displays and screen output. Also collects input from devices such as the keyboard and mouse

- Ntdll.dll: System service dispatcher to executive

- Kernel32.dll: Kernel interface core Windows subsystem

- Advapi32.dll: Core Windows subsystem

- User32.dll: User-mode management subsystem

- Gdi32.dll: Graphical user interface management subsystem

Windows Processes, Threads, and Handles

A Windows application consists of one or more processes. In the simplest terms, a “process” is an instance of an executing program.

One or more threads run in the context of the process. A thread is the basic unit the operating system allocates processor time to. A thread can execute any part of the process code, including parts currently being executed by another thread. Each process provides the resources to execute a program and contains the following characteristics:

- Runs in virtual address space

- Consists of executable code

- Opens handles to system objects

- A security context

- A unique process identifier

- Environment variables

- A priority class

- Minimum and maximum working set sizes

- At least one thread of execution

Each process is started with a single thread that is often referred to as the primary thread. However, the process can create additional threads from any of its existing threads.

A thread is the entity within a process that can be scheduled for execution. All threads of a process share its virtual address space and system resources. In addition, each thread maintains exception handlers, a scheduling priority, thread local storage, a unique thread identifier, and a set of structures the system will use to save the thread context until it is scheduled. The thread context includes the thread’s set of machine registers, the kernel stack, a thread environment block, and a user stack in the address space of the thread’s process. Threads can also have their own security contexts, which can be used for impersonating clients. All threads within a process can access its virtual address space. In general, threads cannot access the memory space that belongs to another process. This protects the process from being corrupted by another process.

Microsoft Windows supports preemptive multitasking, which creates the effect of simultaneous execution of multiple threads from multiple processes. On a multiprocessor computer, the system can simultaneously execute as many threads as there are processors on the computer.

An object is a data structure that represents a system resource, such as a file, thread, or graphic image. An application cannot directly access object data or the system resource that an object represents. Instead, an application must obtain an object handle, which it can use to examine or modify the system resource. Each handle has an entry in an internally maintained table. These entries contain the addresses of the resources and the means to identify the resource type.

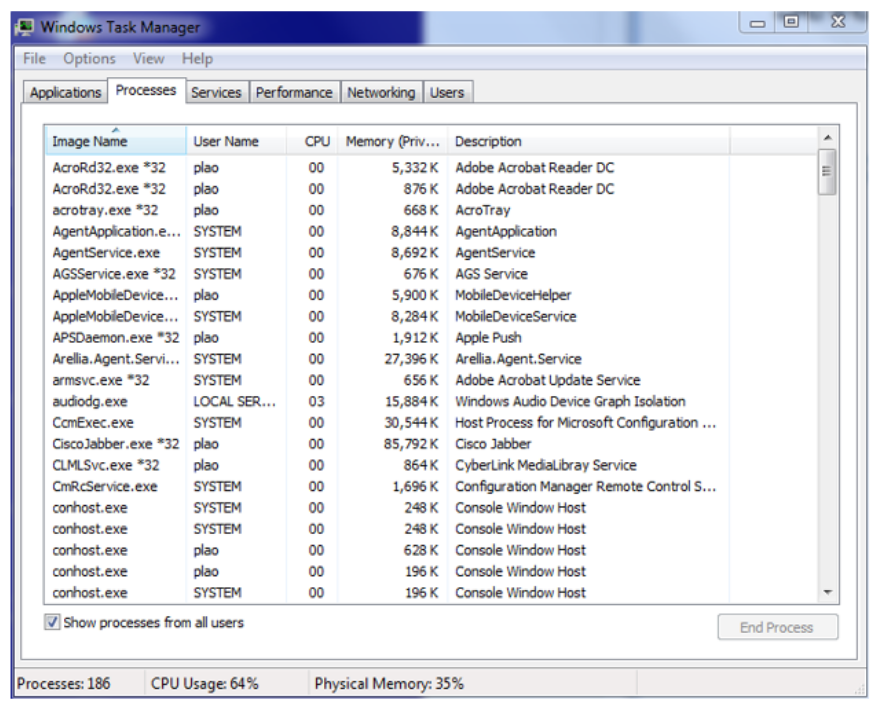

The Windows Task Manager can be used to view the running applications and processes. Here are two ways to start the Windows Task Manager:

- Right-click the taskbar and choose the Start Task Manager option.

- Run the taskmgr command from the Windows command line.

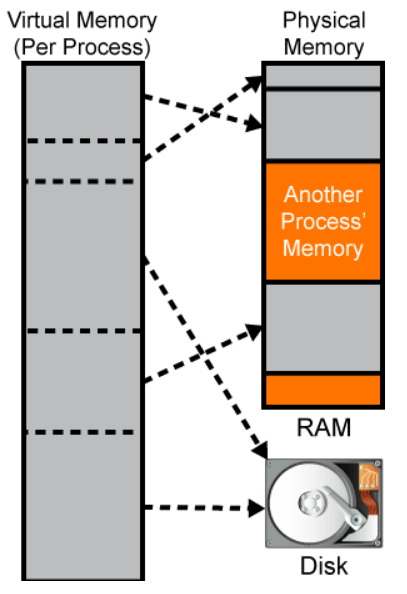

Windows Virtual Memory Address Space

In modern computing systems, temporary data instructions that are processed by the CPU are stored in the computer’s RAM. Virtual memory is a memory management technique that helps the system execute programs when the environment is running low on RAM memory. Virtual memory temporarily transfers content directly from RAM into the disk storage system. This process helps to compensate for a shortage of RAM.

A process is allocated specific memory addresses from the available virtual address space. The address space for each process is private and cannot be accessed by other processes unless it has permission to open the process for read or write access. All Windows applications and processes have to be granted specific access to various kernel system resources or objects, such as TCP ports and Windows sockets. By design, processes are not allowed direct access to kernel level functions. A process “handle” provides the process with access to a specific kernel level resource. Typically, the process has to release the “handle” in order for other processes to be able to access the same kernel level resource. However, if the process has kernel level access to a function and the handle has granted PROCESS_VM_READ (function) access, other processes can be granted read access to the same kernel level function’s memory space via the ReadProcessMemory function. In addition, if the process has kernel level access to a function and the handle has granted PROCESS_VM_WRITE (function) access, other processes can write to the same kernel level function’s memory space via the WriteProcessMemory function. It should be noted that processes need SeDebugPrivilege in order to open such handles. This potential violation of the process’s memory privacy is very common when dealing with malware, and is a technique that is used to insert malicious code with the intent of gaining access to a system.

A virtual address space does not represent the actual physical location of an object in memory; instead, the system maintains a page table for each process. The page table is an internal data structure used to translate virtual addresses into corresponding physical addresses. Each time a thread references an address, the system translates the virtual address to a physical address.

Each process on 32-bit Microsoft Windows supports a virtual address space that enables addressing up to 4 gigabytes of memory. Each process on 64-bit Windows supports a virtual address space of 8 terabytes.

Windows Services

Microsoft Windows services (formerly known as NT services) will create long-running executable applications that run in their own Windows sessions. These services can be automatically started when the computer boots. These services can be paused and restarted, and do not show any user interface. These features make services ideal for use on a server or whenever you need long-running functionality that does not interfere with other users who are working on the same computer.

Services Control Manager is used to start, stop, pause, resume, and configure the services.

To start Services Control Manager using the Windows interface, complete these steps:

- Click the Start button

- Click Control Panel

- Click Administrative Tools

- Double-click Services

To start the Services Control Manager by using a command line, open a Windows command prompt and enter the services.msc command.

Windows File System Overview

The NTFS file system is predominantly utilized in most Windows installations today. A file system is a mechanism for organizing files on storage media. The type of media may influence which file system is appropriate to use. For example, optical media typically uses ISO 9660 or UDF. The focus of this section is on disk storage since the operating system and user data are typically stored on hard disk media.

The following file system options are supported in Windows installations:

- File allocation table: FAT is a general-purpose file system that is supported by Windows and other operating systems such as Mac OS X and Linux. Because of its simplicity and portability, it remains a popular file system. It is mostly used as the default format for USB-based storage media such as flash drives. However, it does have some limitations in terms of the file sizes it supports and the maximum partition size, so it is not widely used for hard drives. There are varieties of FAT known as FAT16 and FAT 32. The FAT32 variant is the most commonly used because it is the least restrictive of the variants, less than FAT16.

- exFAT: The extended version of the FAT file system removes some of the file and partition size limitations of FAT, but is not widely supported on OSs other than Windows and later versions of Mac OS X.

- Hierarchical file system plus: HFS+ is the file system that is used on Mac OS X-based systems. HFS+ permits file names up to 255 characters in length and supports larger file sizes and drive partitions than the original HFS. It is not supported on Windows platforms without the aid of additional software. However, a Windows system can read data from an HFS-formatted drive.

- Extended file system: EXT is the default file system on Linux-based installations. Its most current version is EXT4, which has the benefit of maintaining backward compatibility with the previous versions 2 and 3. It is not natively supported on Windows platforms, but a Windows system can read data from EXT-formatted drives with additional software.

- New technology file system: NTFS is the most commonly used file system in Windows installations. It is natively supported across all versions of Windows operating systems. Mac OS X-based systems can read NTFS partitions but can only write to them by installing additional driver software.

NTFS Basics

The NTFS file system provides many features that make it a good choice for both enterprise-scale systems and desktop systems. Some key features are:

- Performance and reliability

- Compatibility

- Large file and partition size

- Disk quotas

- Recovery features

- Security

It also supports file system encryption to further secure data at rest on the storage media. NTFS supports data access control through security descriptors that include file ownership and permission characteristics for each file. This capability is one reason that NTFS is used so extensively throughout Windows deployments.

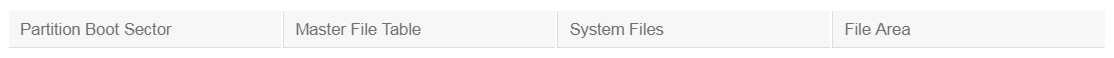

NTFS Volume Structure

Formatting a drive with the NTFS file system creates several system files, and the basic structures for reading and writing files and recording their locations.

The partition boot sector occupies the first 16 sectors of the drive. It contains information that points to the system bootstrap instructions and the location of the Master File Table (MFT), which contains an index of all the files on the partition. The last of the 16 sectors is a copy of the boot sector, which can be referenced if the primary is corrupted.

The MFT contains a file that maps the location of all the files and directories on the partition. NTFS also maintains a mirror or copy of the MFT that can be used if the primary is corrupted. In addition to file location, the MFT stores file attributes such as file name, security descriptor, and time stamps.

The system files are created when the NTFS volume is first initialized. These files are hidden and are used to store metadata about files, NTFS volumes, logs, and file attribute definitions.

The file area is where the files and directories are stored.

NTFS Alternate Data Streams

An interesting feature of the NTFS file system is ADS (Alternate Data Streams) technique. Files in NTFS are stored as a series of attributes such as the file name and date stamp. One attribute is called $DATA, which represents the actual file data, and is known as a “data stream.” However, NTFS allows you to attach ADSs to a file that provides for various interesting cases. ADSs are primarily used by applications to store additional information about a file.

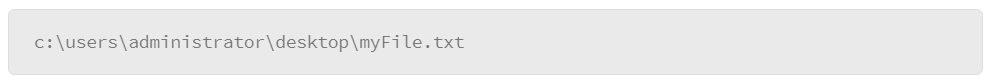

ADS data is not readily visible and can be difficult to detect. In fact, recent versions of Windows just started providing tools for identifying files with ADS. A file with ADS can be referenced with the following format:

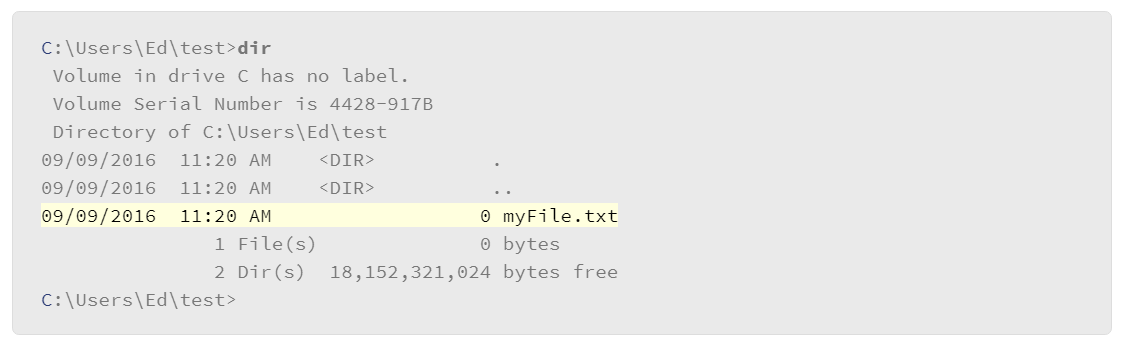

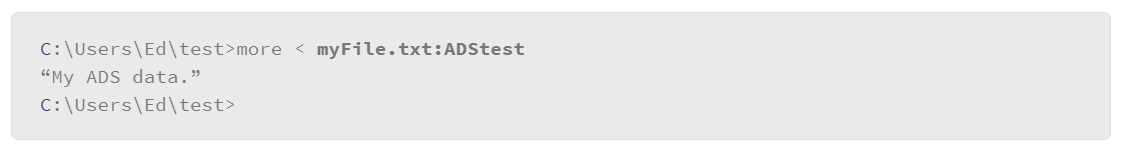

In the example below, the base file name is myFile.txt. The colon character (:) separates the base file name from the name of the ADS, which is ADStest. To test this feature, you can easily create a file with an ADS as follows:

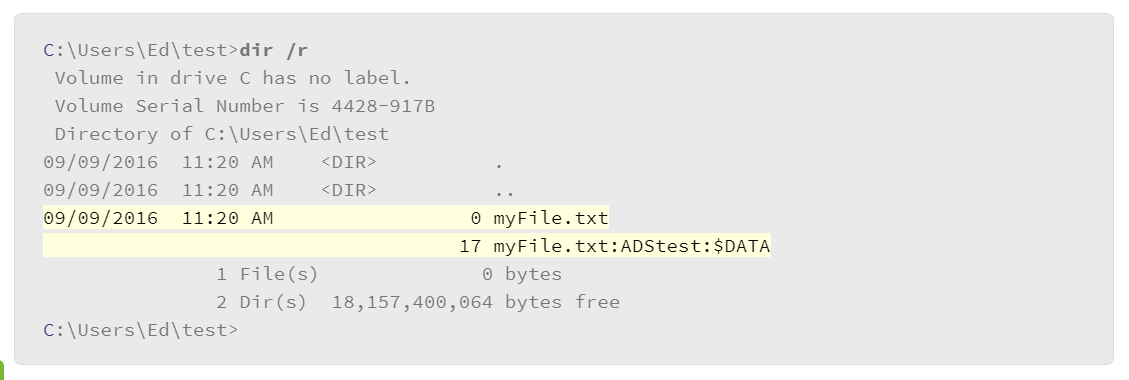

This command sends the text that is specified in the echo command to an ADS that is associated with a file called myFile.txt. List the files in the directory with the dir command to confirm that the file was created.

Note that the myFile.txt file exists, but the size of the file is 0 bytes. The reason for this is that the data that we entered into the file did not go to the primary data stream which is what the dir command is reporting. It went to an alternate data stream that we called ADStest.

To see the data that you put into the alternate stream, do the following:

This illustrates an important ADS issue: it is easy to hide things in an ADS. This technique has been leveraged for malicious purposes, so it is important to be aware of it. Recent versions of Windows have added tools to help administrators identify the presence of ADS. For example, the dir command now includes support for the /r parameter, which lists the ADSs that are associated with a file. Consider the following example:

Note that the dir command with the /r parameter is now reporting the presence of the ADS attached to the file. Also note that the byte size of the ADS is also being reported and that the byte size of the file remains 0.

Windows File System Structure

In a Windows-based system, every storage device that is connected to a host contains its own file system. The Windows OS can be installed on virtually any drive that is connected to the host. However, it is most often installed on the first physical hard drive that is connected to the host. Hard drives, or any storage media for that matter, are identified with letters.

The first hard drive is given the letter C, followed by a colon (:). The Windows file system is not case-sensitive by default (although Windows can be configured to support case-sensitivity). Consequently, accessing the C: and c: drives will reference the same device. Additional storage media is given the next sequential letter designation.

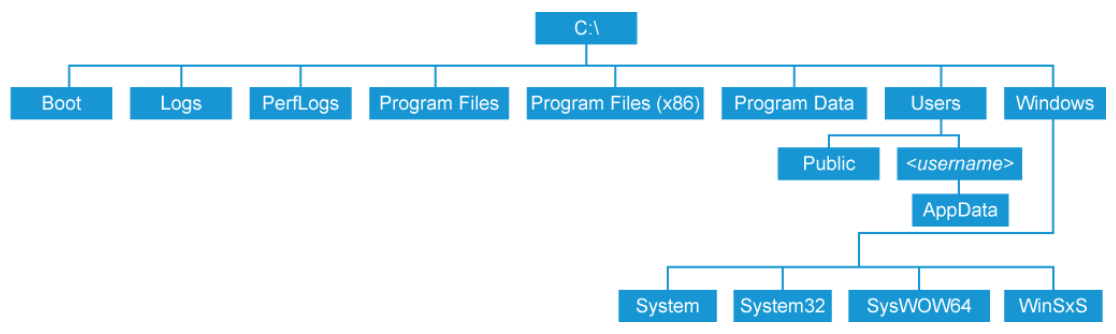

The hard drive on which the Windows OS is installed is typically organized in the following manner:

This is not an exhaustive list of the full Windows file system, but it does include the major directories.

- Boot: A hidden directory that contains system boot files.

- Logs: As of Windows 10, the directory where event logs are stored.

- PerfLogs: Stores performance logs if this feature is enabled in the operating system.

- Program files: In 64-bit Windows installations, stores 64-bit applications.

- Program files (x86): In 64-bit Windows installations, stores 32-bit applications.

- ProgramData: Directory used to store application-need data. Applications are not able to write directly to this directory, but they can create subdirectories used for their own purposes.

- Users: Directory where users store their data. Each user with an account on the system has a folder that is dedicated to them. Users with standard account privileges are only able to access the data in their assigned directory.

- Public: This subdirectory of the Users directory can be shared among all the users of a system. Normally, Windows access controls do not allow users to access data in other users’ directories. However, the public directory allows anyone on the system to store data, making it ideal for sharing data among users.

- username: All users with accounts on a Windows host are given areas for their use. The area for each user resides under the Users directory and bears the name of an individual user’s account. This area allows users to privately store their documents and other data since other users are permitted access to their own directory only. Each user’s directory includes a subdirectory that is called AppData. This location is used by applications that need to store things specific to a user, for example a user’s browsing history. - Windows: The directory that stores the operating system and its various subsystems.

- System: This directory is used to store 16-bit system DLL (dynamic link library) files. In 64-bit Windows installations, this directory is normally empty.

- System32: This directory is used to store 64-bit system DLL files in 64-bit Windows installations.

- SysWOW64: 64-bit Windows is backward compatible with 32-bit applications. This directory stores 32-bit system DLL files.

- WinSxS: This directory stores copies of system DLL files. Often, these files represent older versions of the DLL files that may be required by older applications. The folder name stands for Windows side-by-side because it allows older applications to co-exist with newer ones that require the most current DLL files.

File System Paths

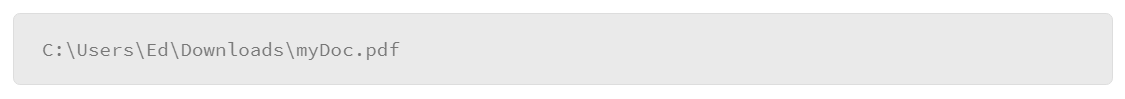

The Windows file system is a hierarchical system in which the root of a disk drive represents the top of hierarchy with multiple levels of directories that can store files or other directories. The term “path” refers to the location of an object, such as a file, which includes the drive and hierarchy of directories that uniquely identify the location of the object. For example, if you use your browser to download a PDF document, the system will store the document in the downloads directory of your user directory, which resides on the disk drive on which the operating system is installed—usually the C: drive.

Each element of the path is separated by a backslash () character. Note that the path starts with a reference to the disk drive, followed by the series of directories that you must traverse to get to the file, and lastly, the file name. This is known as a “fully qualified” path because it includes all the information that is needed to identify the specific location of the file.

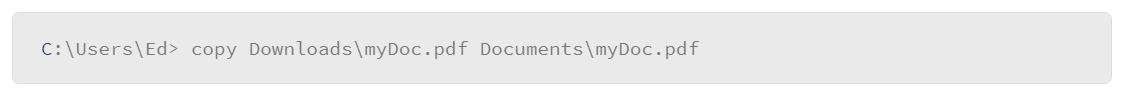

Windows also supports relative paths to identify the location of an object. For example, when you open the command line window, the system puts you in your user directory. The command prompt itself specifies the directory that you are in. To locate the PDF file that you downloaded with your browser, you only need to specify the location of the file relative to your current location. In the example that follows, the user wishes to copy the PDF file from the downloads directory to the documents directory:

Note that with the relative notation, the leading backslash is omitted since that would represent the root of the drive. Because the user was already in their user directory, and both the downloads and documents directories reside in the user directory, only those directories that need to be referenced in the command, along with the file to be copied.

File Naming Conventions

File names in the Windows file system consist of two components:

- Base file name

- File extension

The maximum number of characters that can be used to express a file path is 256 characters. Four additional characters are included in fully qualified names (bringing the total maximum number of characters that is supported to 260), which includes the drive letter, the colon that follows it, the backslash that represents the root of the drive and a null character at the end of the file name to terminate the file name.

However, it should be noted that Microsoft provides the ability to increase the MAX-PATH length within Windows 10.

The unicode version of Windows file IO functions allow for longer paths, approximately 32,767 characters. By utilizing the extended paths, files and directories can be hidden in such a way that some tools are unable to find them. The Windows cmd shell only supports ANSI file paths. Any tool that uses ANSI file IO functions or fails to support \?\C:\ paths cannot access the directories and files that exist after the first 260 path characters.

In a Windows file name, a period or dot character (.) is used to separate the base file name from the extension. However, most other punctuation characters cannot be used in a file name because they have special meanings to the Windows command interpreter.

In Windows, the file extension is used to identify an association between a file and the application that is needed to open or execute the file. The list below contains examples of common file extensions and the applications with which they are typically associated:

- .exe: Executable file

- .txt: Text file

- .rtf: Rich text file

- .pdf: Portable document format

- .bmp: Bitmap graphic image

The list is just a small sample of file extensions. You will mostly see them expressed with three characters but that is not a requirement. File extensions are mapped in the operating system to specific applications. Often, a file format that is used by an application is assigned a unique icon by the application when the application is installed. It registers the extension association so that when a user double-clicks the icon that represents the file, the operating system will know which application to launch. Users can change these mappings but it is not done frequently.

File Properties, Attributes, and Permissions

File properties are essentially details about a file, including the file’s modification and creation date, file size, and other meta information about the file. Specific information that is stored as a property of a file can differ by file type. For example, an audio file will allow you to add a rating, but that same attribute is not supported for text files. Some properties can be modified depending upon the type of file and its ownership permissions.

Another aspect of a file’s properties is file ownership, which allows Windows to enforce a degree of access control so that only the user that creates a file and the administrator initially have permission to access the file. File owners and administrators can grant permission to others. Note that to implement Windows file permissions, you must be using the NTFS file system.

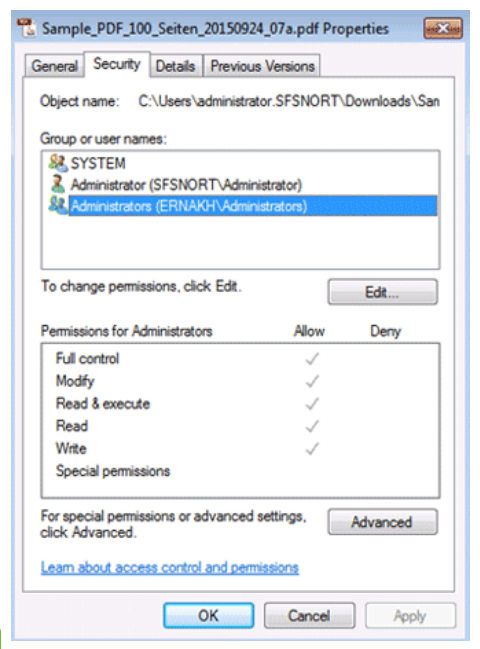

To view or modify the ownership and permission properties of a file, right-click the file, choose Properties, and then select the Security tab.

Currently, the administrator account (represented by the single person icon) and the members of the administrators group (represented by the two-person icon) can access the file. The system user that is listed is a special account that is used by the operating system. By default, the system user is granted full control to every file. You can add users to the list to give others access to the file by clicking the Edit button under the Group or user names box.

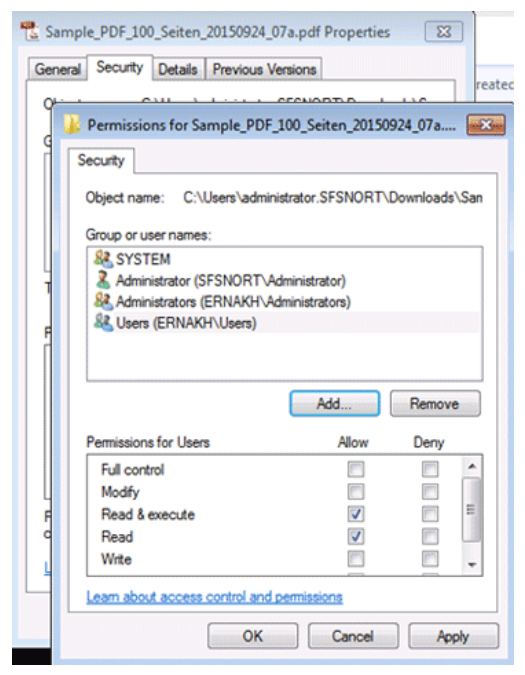

In the figure below, the user has added the Users group to the file properties.

Once you have decided which users should have access to the file, you can specify the permissions to grant each user or user group. The permissions are defined below:

- Read: Allows users to view and list files and subdirectories.

- Write: Allows users to write to files or add files and subdirectories to folders.

- Read and execute: Allows users to view the contents of files, list files and subdirectories, and execute files if they are of an executable type. The read and execute permission does not grant permission to write to the file.

- Modify: Permits users to read and write to files and subdirectories and grants permission to delete files and directories.

- Full control: Permits reading, writing, modifying, and deleting files and subdirectories.

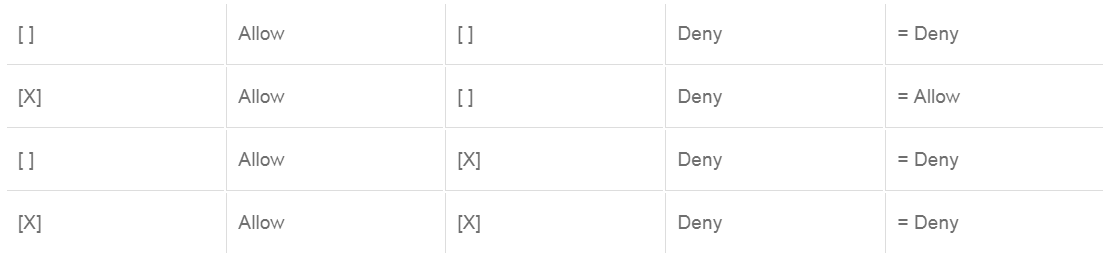

You have the ability to explicitly allow or deny file/directory permissions by checking the boxes in the appropriate column. If a specific permission level is not set, the deny permission will take precedence.

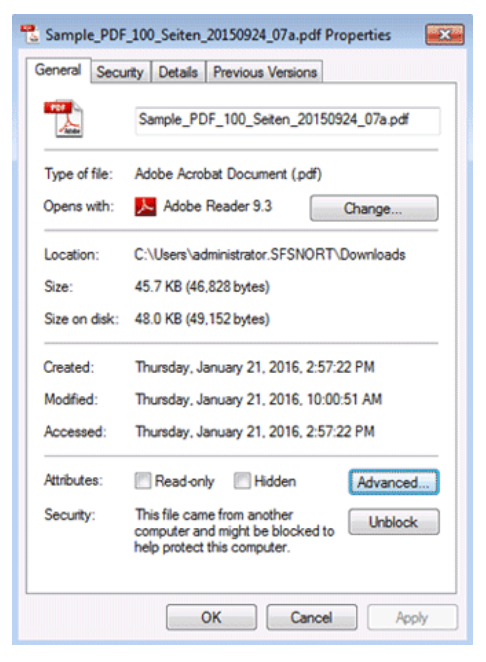

Another aspect of Windows file properties is file attributes, which is metadata associated with every file. File attributes are used to define how the system, applications, or users can interact with a file. You can view many of the attributes that are associated with a file by right-clicking the file and selecting Properties from the context menu.

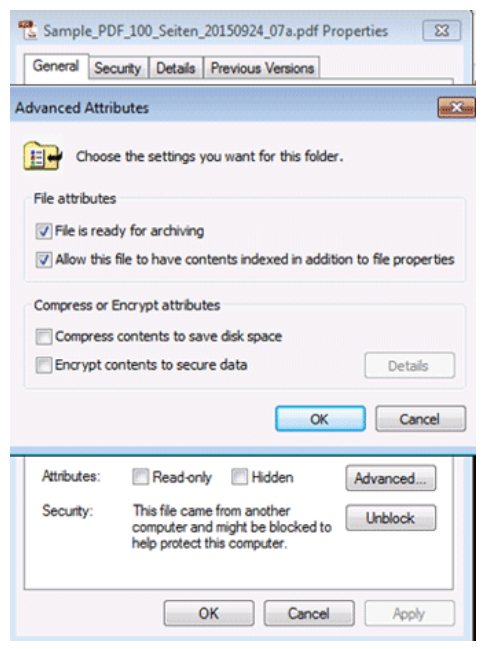

Note the attributes section that is near the bottom of the window. Click the Advanced button to expose more attributes.

The following is a complete list of available file attributes:

- Archive: Used to mark files for backup

- Compressed: Indicates that the data in a file is compressed

- Device: Reserved for system use

- Directory: Marks the object as a directory rather than a file

- Encrypted: Indicates that the file or directory is encrypted

- Hidden: Hides the file or directory from standard directory listings

- Normal: Identifies files that have no other attributes set. It is only valid when used alone

- Not Indexed: The file or directory is not indexed by the content indexing service.

- Offline: File data is not available because it has been physically moved to offline storage; used by remote storage applications.

- Readonly: Applications can read the file data but cannot write or delete it.

- Reparse Point: A file that is a symbolic link

- System: A directory that is reserved for use by the operating system

- Temporary: Indicates that the file is used for temporary storage. Typically, the application using the file deletes it when the file handle is closed.

- Virtual: Reserved for system use.

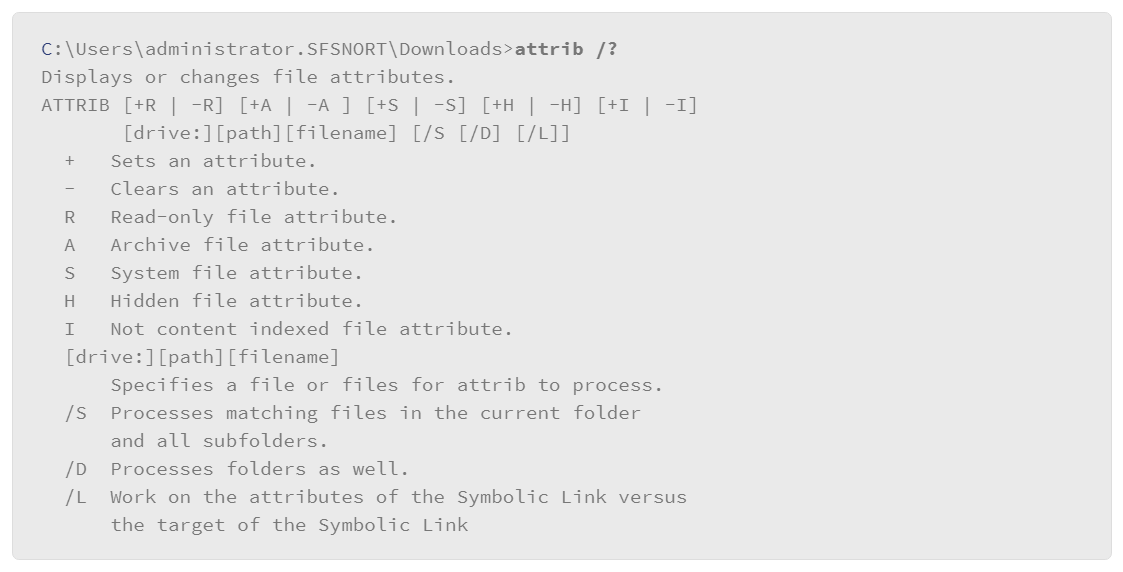

There are several mechanisms for setting or viewing file attributes. For example, from the file properties box, you can view or modify several, but not all, file attributes. You can also view and modify file attributes from the command line with the attrib command. The help text from the command line example that follows shows the various options that you can use with the attrib command:

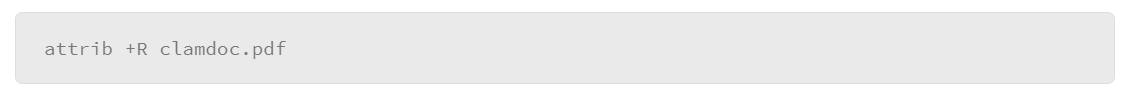

Not all the attributes are available for viewing or change with this command because some attributes are only modified by applications or the system. In the example that follows, the attrib command is used to set the read only attribute on a file:

Windows Domains and Local User Accounts

Windows systems can act as stand-alone hosts, or they can be members of domains. Domains are groups of Windows hosts that are managed by a centralized authority, which is known as a domain controller. One administrative aspect of system management that is handled at the domain level is users and user groups. Stand-alone systems are capable of hosting multiple user accounts; however, each account is managed locally on the host.

Windows Domains

Windows domains represent a closed system of users and computers that can share resources and adhere to one centrally controlled management structure. Each user and machine belonging to that domain must authenticate with a domain controller in order to access the system. A domain controller is a server that is running a version of the Windows Server OS and has AD domain services installed.

A small organization might need only one domain with two domain controllers for high availability and fault tolerance. A larger organization with many network locations will need one or more domain controllers in each site to provide high availability and fault tolerance.

One of the greatest advantages of Windows domain setup is the ability to use group policy to control all the settings of each workstation in granular detail. AD is based on the LDAP which is designed to store information about virtually any type of object in a network that anyone may need to locate. Objects can be users, hosts, devices, or virtually any type of resource. Objects are grouped in structures that are known as containers. Containers can be nested with sub-containers to create a hierarchy structure. Domains are the entities in which containers are stored, and an organization may have one or more domains that can be organized by department or geographic location, for example.

Local Users and User Groups

A default Windows system ships with two default user accounts and several user groups. The default user accounts are guest and administrator. Recent versions of Windows no longer enable the administrator account because it runs with elevated privileges. At system initialization time, the system prompts you to create a custom user account so that you can access the system without the administrator account. The administrator account can be enabled at any time but the best practice is not to do so. If an an administrator account or an account with administrator privileges is compromised, malicious code has greater access to critical system resources. Users that need to perform a task with administrator-level access can always select the “Run as Administrator” option when they select the object to act on, such as a file or connected device.

The second default user account is called guest. This account is disabled by default and for most installations it should remain this way. It is intended for situations where a Windows host may be deployed in a public space or a location where it is likely to be accessed by many people that do not necessarily have accounts on the host. It grants a limited amount of privilege and is not protected with a password. Normally, customizations that a guest user makes during a session are erased when the guest user exits. When a new guest accesses the host, they are presented with a default desktop environment from which the user can launch authorized applications and access authorized system resources.

User groups determine the level of privilege that users have on the system. For example, placing a user in the administrator’s group grants that user administrator privilege. Several user groups are present on a standard Windows installation that grant specific rights to the users that belong to the group. For example, a user can belong to the backup operator’s group, to perform backup and restore operations. Most users will be assigned to the users group, allowing them to perform common tasks, run applications, use resources such as network printers, or lock and shutdown the system.

Starting with the release of Windows 8, Windows products have been gaining greater integration with Microsoft cloud services. To support these features, you could log in to a Windows system with a Microsoft account rather than a local account. This allows user data to get synchronized between multiple desktop devices and mobile devices. For example, your files that are stored in the Microsoft cloud drive are automatically available at login time. And your desktop profile migrates to whatever host you log in to with your Microsoft account. A Microsoft account is available to any user that subscribes to a public Microsoft service, such as Hotmail or its web-based applications. Users of these versions of Windows can still create and use a local account on the host, but they lose cloud functionality unless they sign in to these applications manually.

Creating a Local User Account

There are several ways to access the application to manage user accounts on a Windows system, but the most common method is through the control panel. The exact method for accessing the control panel depends on the version of Windows, but, usually you can get to it from the Start menu in the lower-left portion of the screen. From there, you will either see an option to navigate to the control panel or, in recent versions of Windows, you will see a Settings option that opens a tablet-friendly version of the control panel. With the control panel or settings window open, you can navigate to the user accounts selection, where you can create or manage local user accounts.

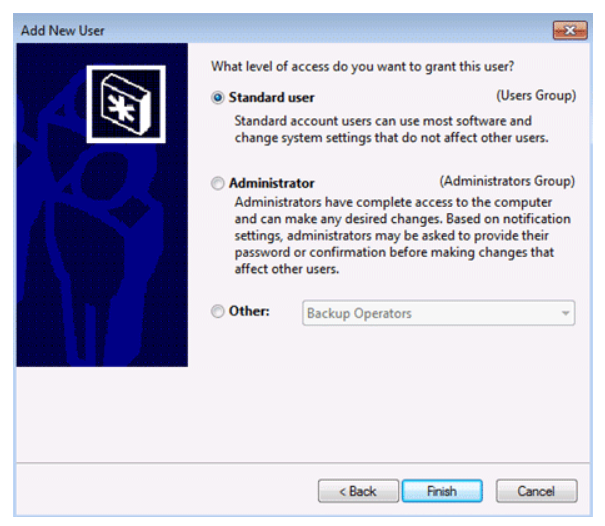

When you create an account, you are prompted for the user name and domain. If you are creating a local account, you can leave the domain field blank. Next, you are prompted to provide the level of access to grant to the user. Choose standard user access, administrator access, or other, which lets you specify the privilege level from a drop-down list of options.

After making your selections, click the Finish button to complete the process. When the user attempts to log in with the new account, they are prompted to create a password for the account. Note that to create an account, you must either be logged in as the administrator or be a member of the administrator group.

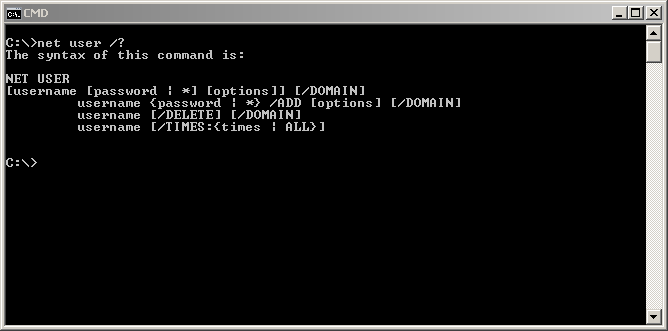

User accounts can also be created through the net user menu from the command shell.

Windows Graphical User Interface

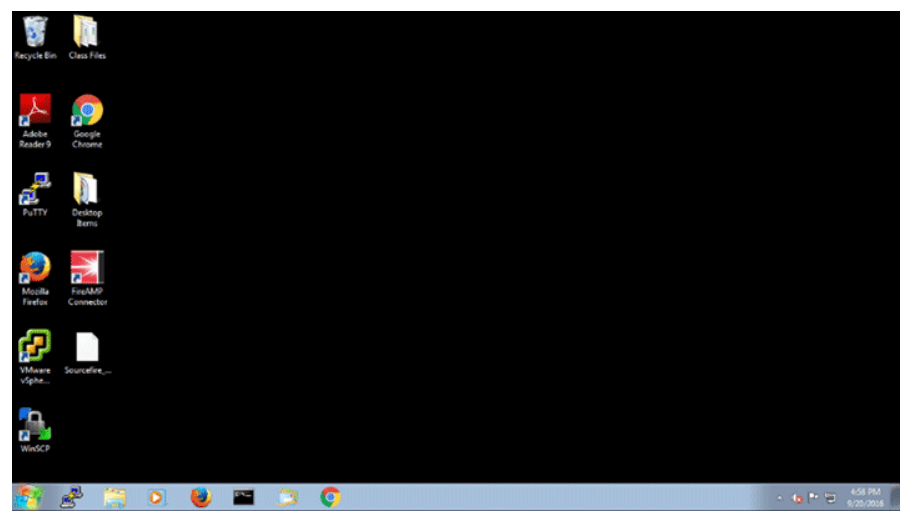

One distinguishing feature of the Windows OS is that it is operated primarily from the graphical interface. It has a command line from which you can execute commands and navigate the file system, but usually a Windows-based host is operated from the graphical interface. The following figure shows a typical Windows 7 desktop.

The main panel of the screen is known as the desktop. Each user is given a desktop, which is an environment that the user can customize in various ways, such as using an image for the desktop background or changing the color scheme. The desktop can also be used to store files, folders, or application icons. The recycle bin icon in the upper-left portion of the desktop is reserved for deleted files. Rather than making files unavailable immediately after deleting them, Windows stores deleted files in the recycle bin. Files are not fully deleted until you empty the recycle bin.

The lower portion of the screen contains the task bar which is further divided into three primary areas:

- Start menu: The icon that is at the far left portion of the task bar is the Start menu. The start menu gives you access to all your applications and other special features of the system such as the control panel. It also contains a field that you can type in to search for items or run commands.

- Quick launch icons: The middle portion of the task bar contains a series of quick launch icons, which act as launch buttons for applications that you place in the task bar. It also creates an icon for each application that is currently running. Clicking the icon of a running application brings it to the foreground so you can use it. You can also pin application icons to the task bar for easy access to frequently used applications.

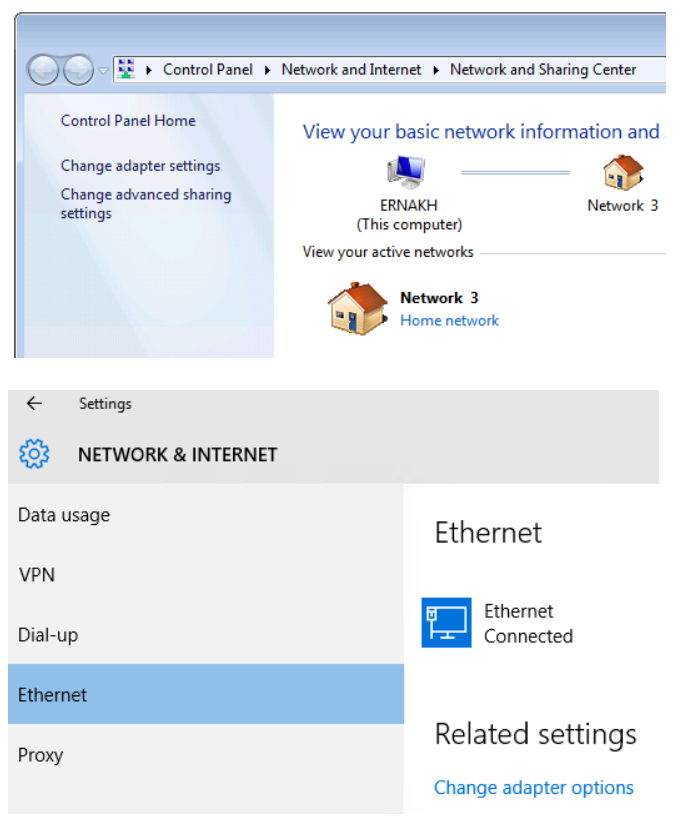

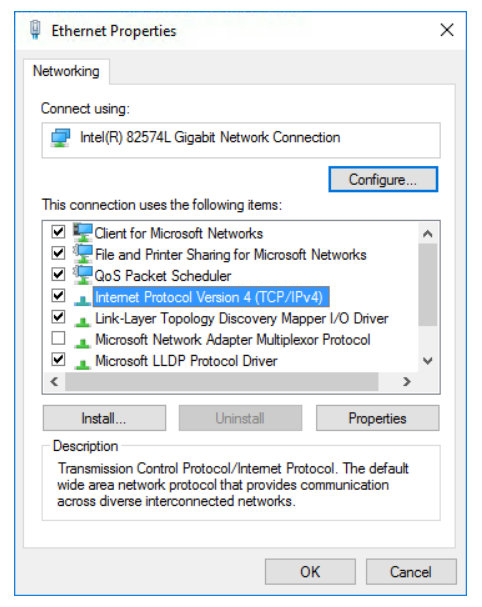

- Notification area: This area contains several features for viewing notifications and controlling applications or processes that run in the background. The arrow icon opens the system tray which is where you can access options for controlling background applications. The flag icon lets you view system notifications and the icon to its right lets you view and control networking status. The shape of this icon will change depending upon how you are connected to the network. If you are wired to the network over an Ethernet connection, the icon will appear as a computer terminal; if you are connected over a wireless adapter, you will see the wireless icon here instead. This area also contains a clock so you can view the date and time. Lastly, there is a rectangular button in the far right portion of the task bar that is used to minimize all the running applications and show you the desktop.

Windows Context Menu

Another feature of the Windows desktop is the ability to bring up a context menu in virtually any part of the graphical interface. Right-click an item to open a context menu. Windows keyboards also contain a context menu key that exposes a context menu at the location of the mouse pointer. The context menu presents menu options that are relevant to where you opened it. Also, some third-party applications add items to the context menu.

Windows File Explorer

Windows provides a tool for managing files and navigating the file system, which is known as the Windows File Explorer and is sometimes referred to as Windows Explorer. It is a utility that runs in the graphical environment and can leverage many of the features of the graphical environment, such as drag-and-drop and the context menu.

The Windows OS is known for its rich graphical interface which makes for an intuitive and easy-to-use end user platform. Though it does provide a command line interface which is also quite robust, most users choose to operate the system using the graphical interface.

Run as Administrator

Certain tasks that you need to perform to administer a Windows system may require administrator privileges. Normally, the command interpreter runs with the permissions that are configured for the user who is operating the command line. However, you can elevate your permissions to administrator level using the following methods:

- Right-click a command icon: If there is a command you need to run as administrator, you can use the Windows File Explorer to find the command and right-click it to bring up its context menu. From there, you can Run as administrator, as seen in the figure. This technique can be useful in situations where you need to install an application with the administrator context. In the figure, the user is installing an AMP for endpoints connector which requires administrator privilege

- Open the command interpreter as administrator: Right-click the icon for the command line to see that the same option, Run as administrator, is also available. The difference is that all the commands that you execute from the command line will run with the administrator context.

Windows Command Line Interface

In addition to the rich graphical environment, Windows includes a robust command line interface that you can use to execute applications, manage files, and navigate the file system. You can also store commands in a text file and execute them, just as you would a shell script in Linux environments.

When using the Windows command line interface, consider the following:

- Case sensitivity: By default, Windows commands, file paths, and file names are not case-sensitive. However, the case-sensitivity of the text is preserved when creating a file or directory. Windows will not take case-sensitivity into account when expressing an item in the command line. However, Windows can be configured to support case-sensitivity.

- Directory references: Directory structures in a Windows installation are referenced with a starting point of the storage media on which the file you need to reference is located. Storage media is assigned a drive letter. After the drive is identified, you list the directories that the system must traverse to access the file. Drives, directories, and files are delimited with a backslash (\) character. For example:

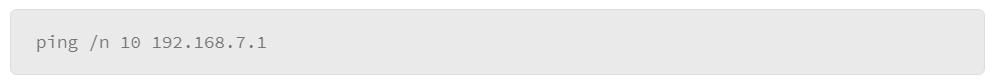

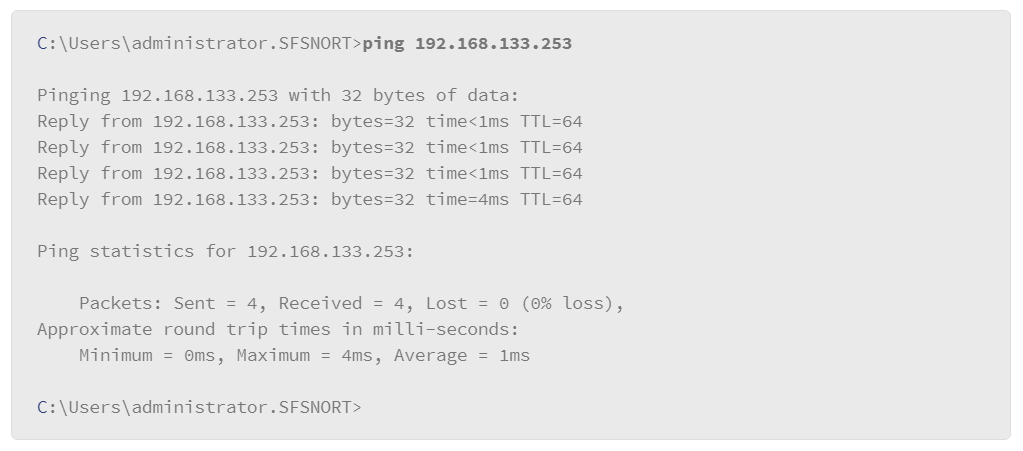

- Commands and command options: You can execute commands from the command line. Often, the commands you execute will accept options. Command options are preceded with a forward slash (/) character. In the example that follows, a ping command is shown with an option to send a specific number of echo request messages:

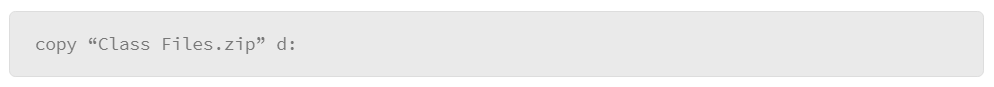

- Accounting for spaces in file names: The Windows file system allows for file names to contain spaces, which can cause problems in the command line because a space is typically used to separate a command from its arguments. To ensure that a space in the file name is interpreted correctly, enclose the file name in double quotation marks (“).

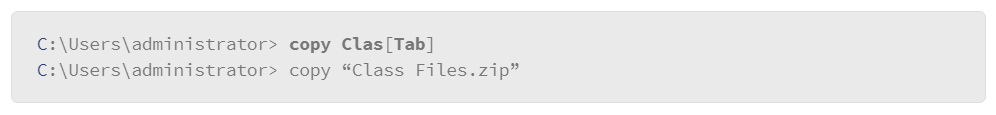

In the example, the user is copying the Class Files.zip file to the D: drive. Note that the file name contains a space and that the user enclosed the file name in double quotation marks (") to prevent the command line from misinterpreting the command. - Auto-complete: A useful feature of the command line is the ability to automatically complete commands that reference directories or files. This is accomplished by pressing the Tab key as you enter file or directory references in the command line.

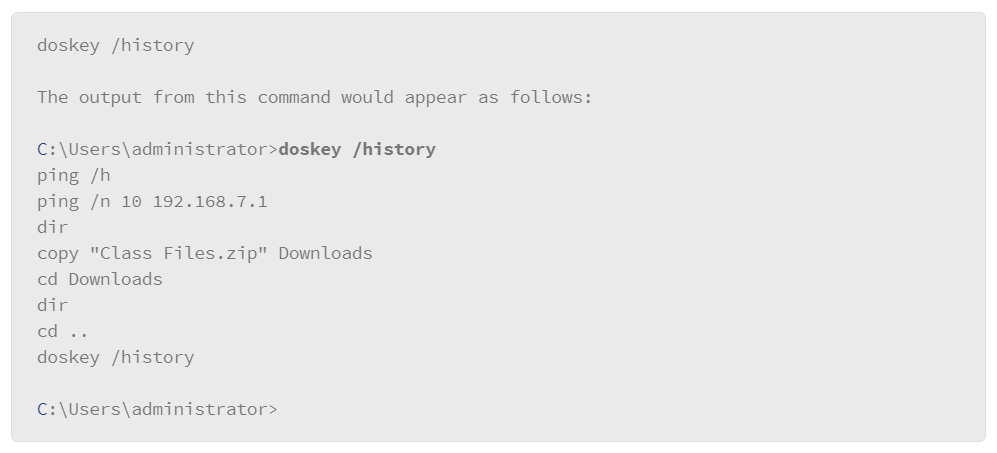

In the example, the user entered the copy command followed by a portion of the file name. Then the user pressed the Tab key to autocomplete the file name reference. If the command interpreter can determine the remaining portion of the file, it will complete the file name automatically. If the file does not exist in the location that was specified by the user, the command interpreter does nothing. In this case, check your syntax or spelling. Also note that the command interpreter recognized that the file contained a space character in the name and correctly enclosed the file name in double quote characters. - Command line history: The Windows command line maintains a history of the commands you used throughout the command line session. Once you exit the session, the command history is erased. A new command history is created the next time that you open the command line. To access recently used commands, use the up or down arrow keys. You can list the command history with the following command:

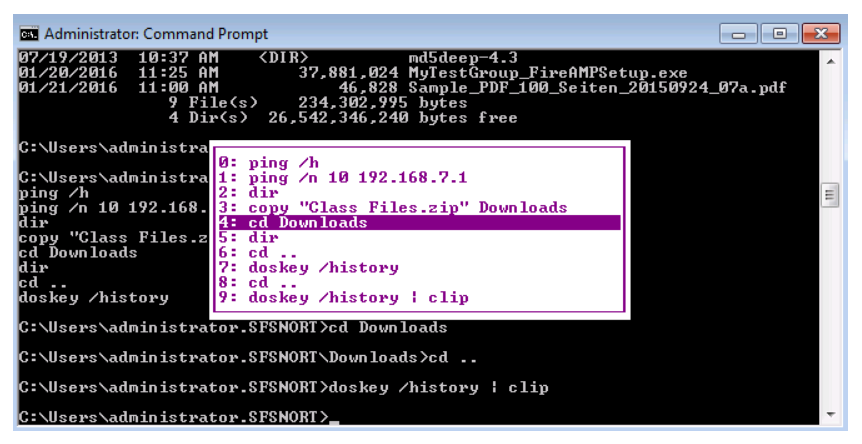

Another option is to press the F7 key while you are in the command line window. This opens a box in your command line session that lists the command history. Navigate the box with the up and down arrow keys or use the Home and End keys to go to the beginning and end of the command history list. You can also use the Page Up and Page Down keys to move a page at a time if the list spans multiple pages. When you highlight the command that you wish to use from the list, press the Enter key to execute it. The figure shows an example of the command history box after opening it using the F7 key:

The Windows command line history provides another feature that you may find useful if you are entering a lot of long commands that you don't want to type. Type a portion of a command and press F8 to have the command interpreter fetch the most recent command that begins with the string that you typed. If the command that is presented is not the one you want, press F8 again and it will search the history for the next most recent instance of the string.

File and Directory References from the Command Line

The Windows OS designates all storage media as unique entities with their own file systems. Therefore, referencing a file or directory location will always begin with a specific drive letter. A user can easily switch from one drive to another by simply specifying the drive letter followed by a colon.

With the drive that you wish to use selected, you can begin to navigate its directory structure, manage files, or execute commands from the command prompt.

The Windows command prompt allows you to reference files and directory locations in one of two ways:

- Fully qualified reference: Using this method, you must enter the entire directory starting from the root of the current drive or a drive letter if the item that you wish to reference resides on a different drive.

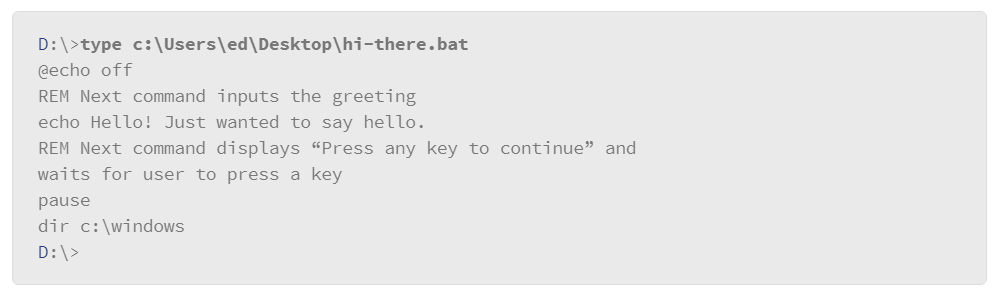

In the example, the user executed the type command, which is used to print the contents of a file to the screen. The user’s command prompt was in drive D:, but the file that the user was interested in was on the C: drive. The user referenced the file using the fully qualified path to the file. - Relative reference: Relative references to file or directory locations take into account the current file system location as the starting point of the reference. If a file or command resides in a directory level that is higher than the current directory, use the double dot (..) notation to move up the directory structure

Windows PowerShell

Although the Windows command line has a rich set of features, including the ability to create batch file scripts, it lacks the ability to interact with core Windows OS functions and graphical interface. The Windows PowerShell overcomes these drawbacks by providing a scripting environment that is deeply integrated with the operating system and graphical interface. It also provides a command line interpreter for executing commands and directing their output to the screen, as you would by executing a regular command from the command line. The true power of the PowerShell however, is the ability to use it as a scripting language for automating tasks. It is also interoperable with other operating systems such as Linux and OS X.

As of Windows 7 and Windows Server 2008, PowerShell has been included as an integrated component of the operating system. It can run on versions before Windows 7, but it has to be installed separately. Another recent development regarding PowerShell is that it became an open source project in August of 2016, paving the way for support under other operating systems. Open source code can be obtained from GitHub.

Windows PowerShell can execute several types of commands:

- cmdlets: Pronounced “command-lets,” cmdlets are programs that are designed to interact with PowerShell.

- PowerShell scripts: These are sequences of PowerShell commands that are contained in a file that can be executed. PowerShell script files have a .ps1 file extension.

- PowerShell functions: Functions are code snippets that can be referenced from within a script. Functions can be crafted to accept parameters.

- Standard executable files

PowerShell was also designed with security in mind. First, to execute PowerShell commands locally with escalated privileges, you must use the “Run as Administrator” option. Second, the PowerShell Remoting function is disabled by default, and once enabled, administrator rights are required to connect to a remote computer via PowerShell. Lastly, PowerShell includes an execution policy to determine whether the system can run PowerShell scripts at all, or, if it can, the execution policy can enforce whether the script has to be digitally signed.

There are four PowerShell execution policy elements as follows:

- Restricted: Default execution policy that completely restricts the use of PowerShell scripts on the system

- AllSigned: Indicates that any PowerShell script that you attempt to execute must be digitally signed

- RemoteSigned: The recommended execution policy mode that indicates that externally downloaded scripts must be digitally signed, but scripts that are created locally do not need to be signed. Windows considers a PowerShell script to be an externally downloaded script when the file contains an ADS to indicate that the file came from the Internet zone.

- Unrestricted: This places no restrictions on running PowerShell scripts.

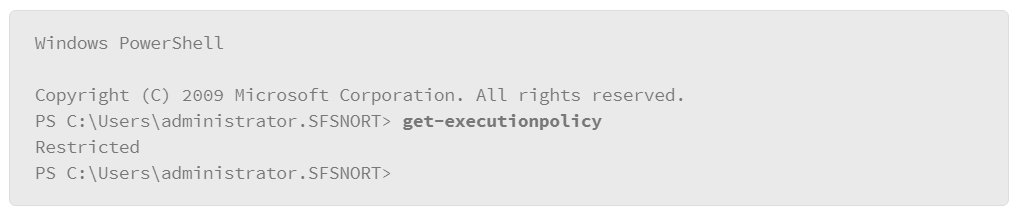

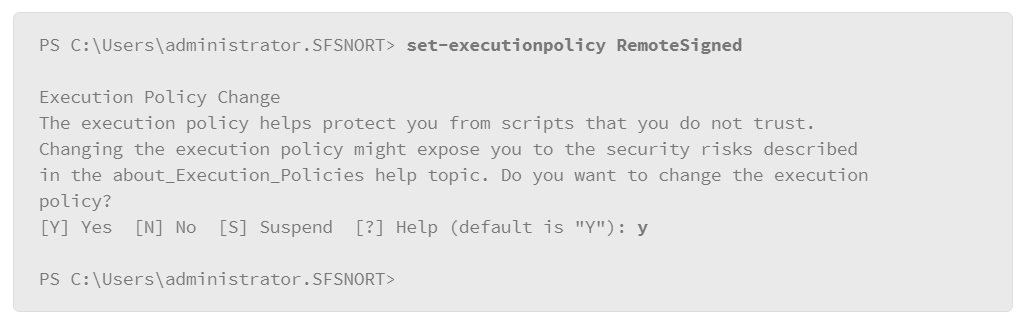

From within the PowerShell environment, you can determine the current execution policy by using the get-executionpolicy command. You can also set the execution policy by using the set-executionpolicy command from within the PowerShell environment.

Another aspect of the security that is built in to PowerShell is that it does not run commands from the current directory. It searches the directories that are stored in the PATH environment variable. If the PowerShell script that you are trying to call up is not in one of the directories that are specified in the variable, the system will return a “file not found” error, even if the script is in the same directory where you attempted to execute it. To execute a PowerShell script, it must be in the PATH variable, or you can provide the fully qualified path. For scripts in the same directory, put a period+backslash (.) or period+forward slash (./) in front of the script name to instruct the system to search for the file in the current directory.

Entering PowerShell

The Windows PowerShell environment can be initiated in several ways. First, you can go through the start menu and find the icon to start a PowerShell session. If you simply click the icon, you will be restricted in what you can do. However, if you right-click the icon and choose the “Run as Administrator” option from the context menu, you will have full control of the PowerShell session.

Another option is to start a PowerShell session from the standard command line window. Again, for full control, you should be utilizing the command line as an administrator. The command to start the PowerShell is start powershell. The new window opens with the PowerShell command interpreter (it may look similar to the standard command line window, or have a different color scheme). What you see depends on the PowerShell version that is running on your system.

In all cases, the PowerShell command prompt starts PS, immediately followed by the directory path from which you started the PowerShell session. Note that the banner indicates that you are in the PowerShell command interpreter environment, as does the title bar of the Window running the PowerShell.

Test the PowerShell session by running a simple command as shown below:

In the example, the user executed the command to check the PowerShell execution policy. The value that it returned was “restricted” which means this host is not configured to run PowerShell scripts. To enable PowerShell script execution, enter the following command:

Note that the system returns a warning and gives the option to continue or exit. The default is to continue. Press the Enter key, or enter the letter y followed by the Enter key, to accept the default.

Another alternative for executing PowerShell commands or executing scripts is to use the -command option with the PowerShell command line start command, as follows:

This starts the PowerShell and executes the command that you enter as the argument to the -command option. This method closes the PowerShell window after the command executes, so it might be better suited for launching scripts. You, can, however, use the -NoExit option to leave the window open when the command finishes.

Using PowerShell

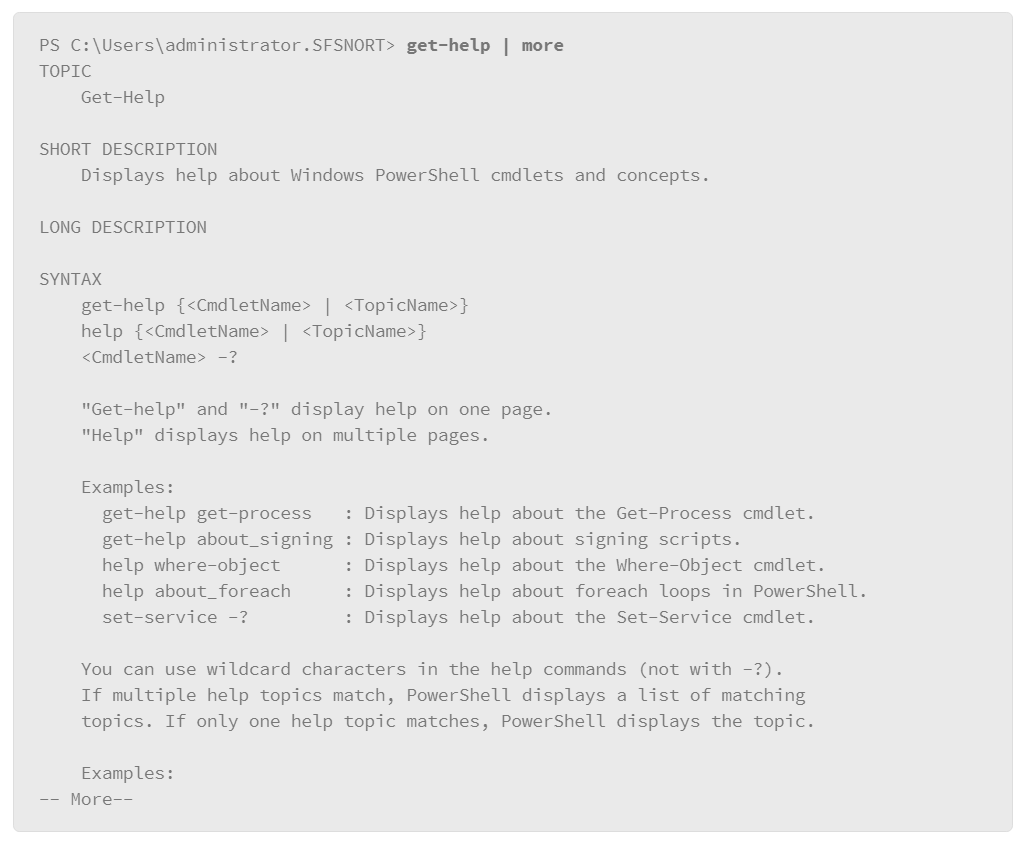

When you first start using PowerShell, you should explore the help system, which provides a quick means of giving you information and usage examples. Invoke the help system with the get-help command. Include the more command to prevent information from scrolling off the page before you have a chance to read it.

This is a partial representation of the help page, but it shows syntax examples, and examples of how to get help on specific commands.

To get the most out of the PowerShell, explore the four levels of help information further:

- get-help

: With no further parameters, returns the least amount of help information</li>

- get-help

-examples: Provides basic help information with examples.</li>

- get-help

-detailed: Provides a more detailed amount of help information with examples.</li>

- get-help

-full: Provides the most information with examples and greater technical depth.</li> </ul>

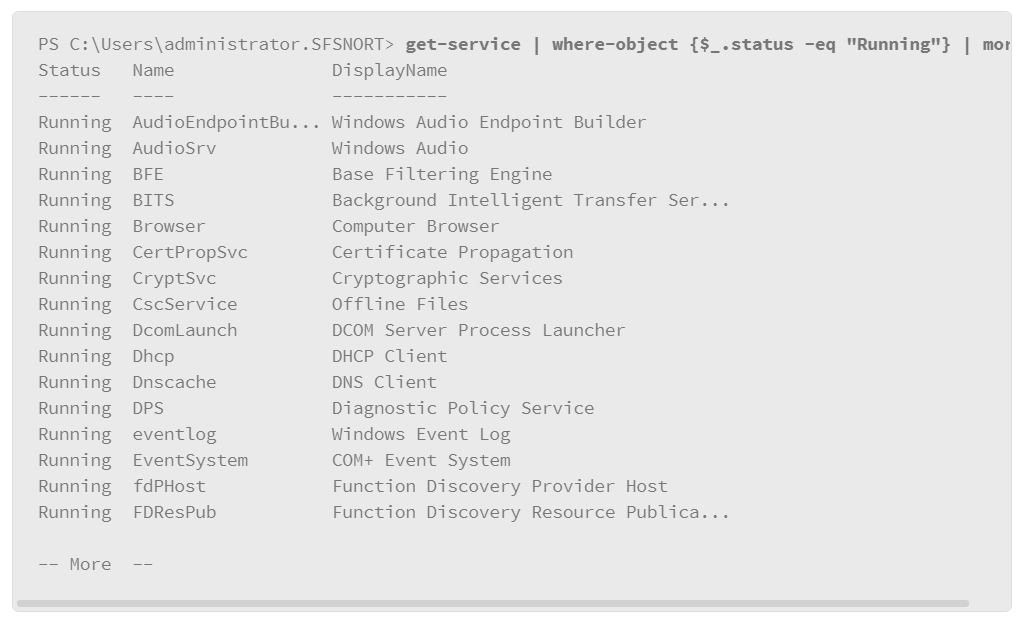

The previous example, where the get-help command output was piped to the more command, is another powerful capability of PowerShell. Piping the output of one command to the input of another greatly increases your productivity with PowerShell by getting directly to information that you may find useful, rather than wading through long lists of command output feedback. In the example that follows, you may be interested in finding out about services that are installed on the host that you are evaluating. Use the get-service command to do so, but it yields a great deal of information including stopped services and running services. You may only be interested in the running services, so pipe the output of get-service to the where-object command to specify the output criteria.

The following is an example of how to execute these commands to filter the output to just running services. This output is also piped to the more command due to the size of the PowerShell window. This way, the output does not scroll off the screen before you have a chance to read it.

Now the command output is more precise and usable. The parts of the command that make this work are the parameters of the where-object command. The first parameter specifies the field of information that you are interested in. The second parameter uses an equality operator to let you specify the string in the field that you wish to search for.

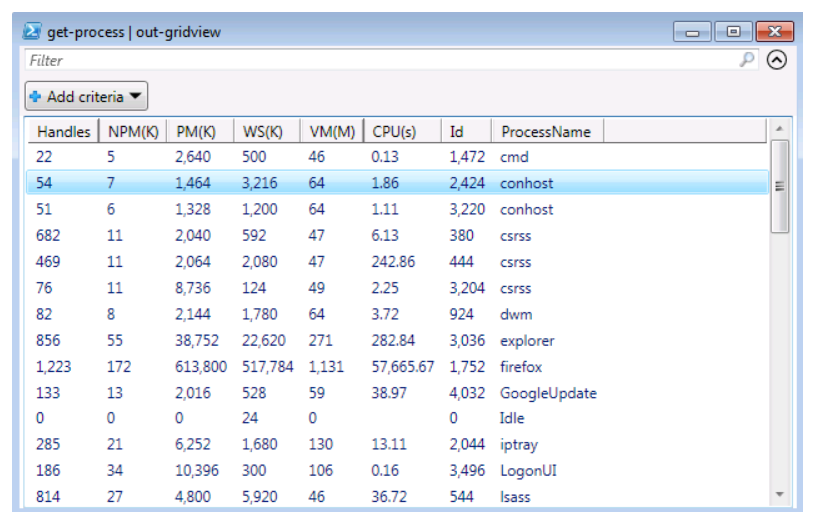

Another interesting feature of PowerShell is the ability to send output from a command to an interactive table in the graphical environment that you can sort and filter. The example that follows places the output of the get-process command to the interactive table.

This command produces an interactive table as shown in the figure:

The window is the output of the command in a graphical table that you can interact with. Click column headings to sort on a column, filter items based on a fstring that you enter in the Filter field near the top, and add criteria to further filter the output. For example, if you click the Add Criteria button and select handles, you can enter logical operators as a filter, such as handles with a number greater than, less than, or equal to a value that you enter.

In this example, the output from the get-process cmdlet includes the following:

- Handles: The number of handles that are opened by the process

- NPM(K): Nonpaged memory in kilobytes

- PM(K): Pagable memory in kilobytes

- WS(K): The working set of memory pages that is used by the process in kilobytes

- VM(M): Virtual memory, in megabytes, that is consumed by the process

- CPU(s): Processor time, in seconds, that is consumed by the process

- ID: The process ID

- ProcessName: The name of the process

At a glance, this gives you an idea of the processing resources that are consumed by individual processes at the time that the command was executed. Clearly, the Firefox application was consuming most of the processing resources when the get-process cmdlet was executed.

Importing PowerShell Functions

PowerShell users have an active community that features sites, blogs, and various resources for users to support each other and share code. By taking advantage of these resources, you may find that a problem that you need to solve with PowerShell has already been solved by others. If you obtain code from another source or you wrote a function that you wish to use as a script, use the import-module command to do so.

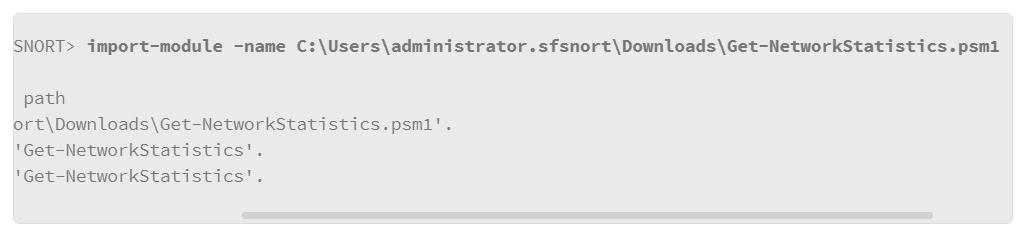

For example, the Microsoft blogging community makes many useful code examples available. One entry, which was written by Shay Levy, includes a PowerShell function to find running processes that are listening for connections with their associated port numbers. You can copy the code example and import it, so that the function is available to run on your system as if it were a standard cmdlet. The process for performing the import is as follows:

In the example, the import-module command uses the -name parameter to identify the file with the code sample that you wish to import. It also adds the -verbose parameter to provide verbose output as it processes the file, which could provide useful information if the import were to fail. The extension of the file name is also provided; the convention is to use the .psm1 extension for importing this type of code sample.

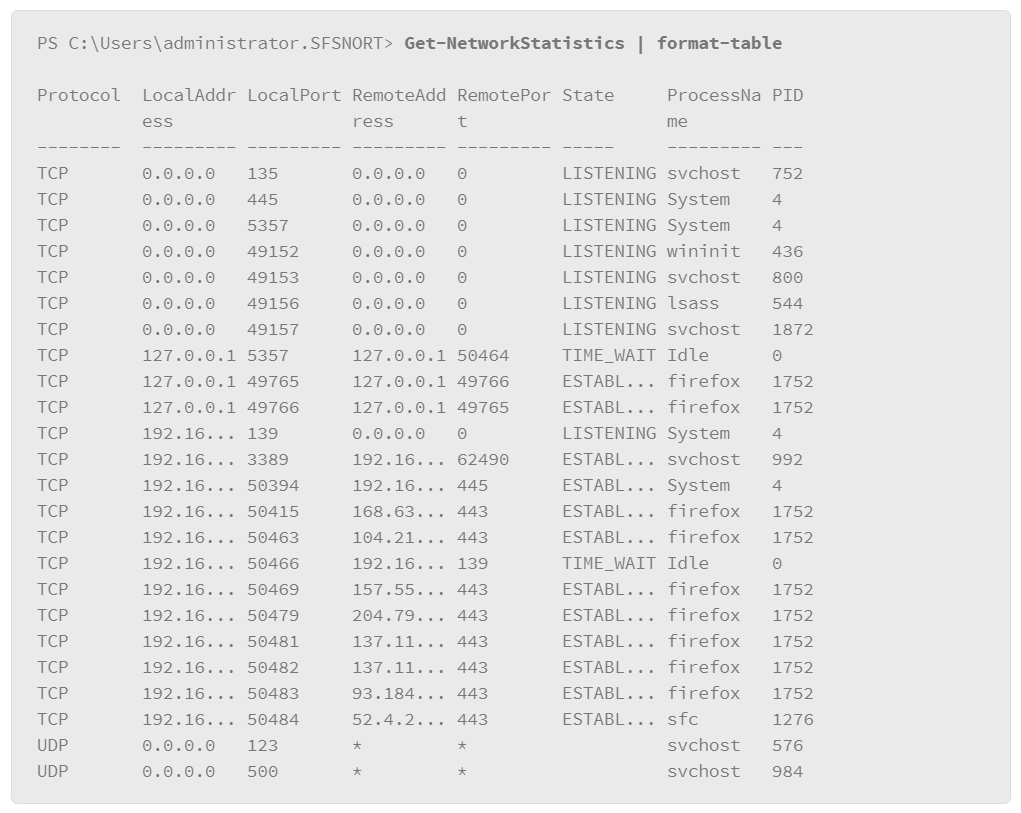

With the code sample imported, execute it as if it were a regular cmdlet as follows:

The example output is truncated, but you can see that it provides a great deal of information which could be useful if you are investigating suspicious processes that have opened a port to listen on, for example. Note that the data within some of the columns is truncated as well. Adjust the width of the PowerShell window to see the entire message for each field in the output.

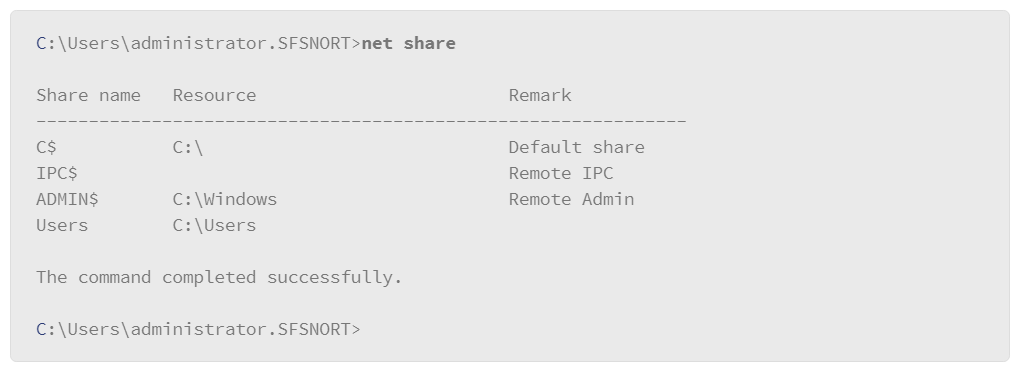

Windows net Command

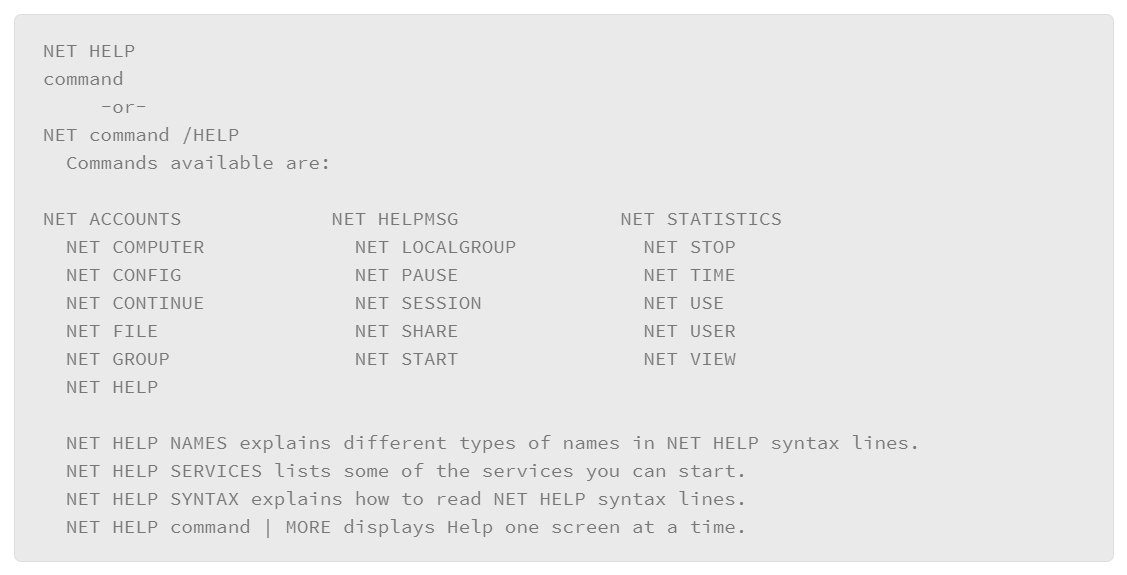

The Windows OS contains a robust suite of commands that are comparable to the command sets that are available in any other operating system. However, Windows OS includes a set of commands that are specific to Windows administration and maintenance. These commands are known as the net commands since the commands start with the term net and are often used to manage network resources, although there are also options that focus on local system resources.

To get information about using these commands, enter net help at the command prompt to display a list of various net command options, and instructions for getting help with specific options.

The syntax of this command is:

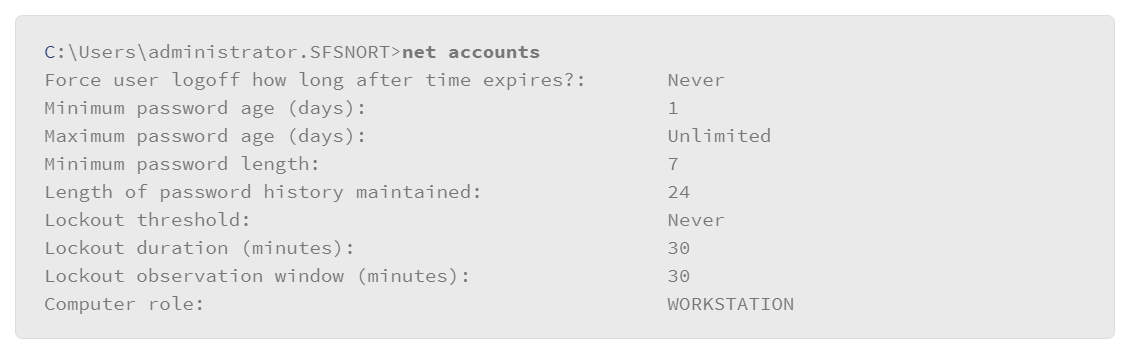

An example of using a net command is to view or edit local user account login policy. You can use the net accounts command as follows:

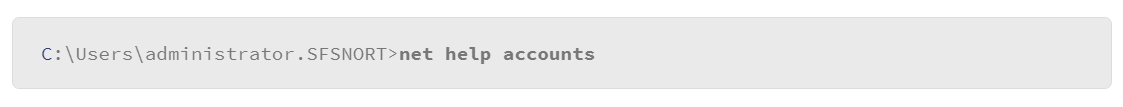

With this usage, you can view the local user login policy, and modify the policy if you wish. Currently, based on the feedback from the net accounts command that was issued previously, the Maximum Password Age is unlimited. You prefer that the user of this host periodically changes their password, but you are not sure how to structure the command. The following syntax to will provide help:

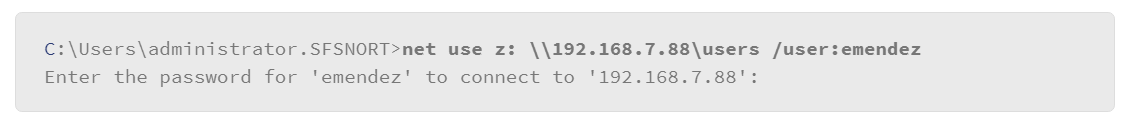

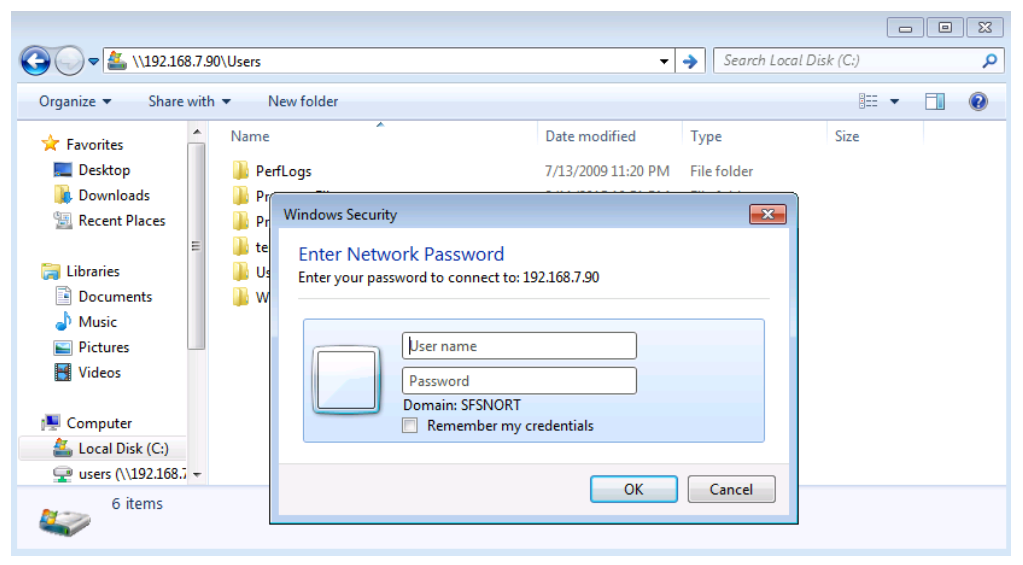

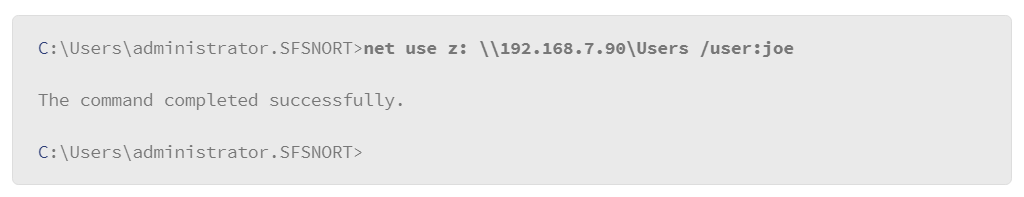

There are many more uses for the net commands. For example, if you need to mount a file share to your Windows host, use the net use option of the net command.

This command mounts a share to the remote host 192.168.7.88 and it connects to a share that is named “users.” When the share mounts, it will be mapped to the driver letter z:. So, the local users of this host will be able to use the remote share as if it were a locally connected disk drive. Lastly, the command specified a user name to log in with on the remote host. If the user name is a valid user on the remote host, the user is prompted for a password. Upon entering the correct password, the share becomes available to use on the local host.

This last example demonstrates how to use the command to stop and start network services. First, you must know the name of the service that you wish to control. In the example, the system admin will use a service that is called FileInfo. The following represents the sequence of commands to stop and start the service:

Mastering net commands is an important skill for Windows administrators. You've seen just a few examples, but there are many more useful features of the net commands.

Controlling Startup Services and Executing System Shutdown

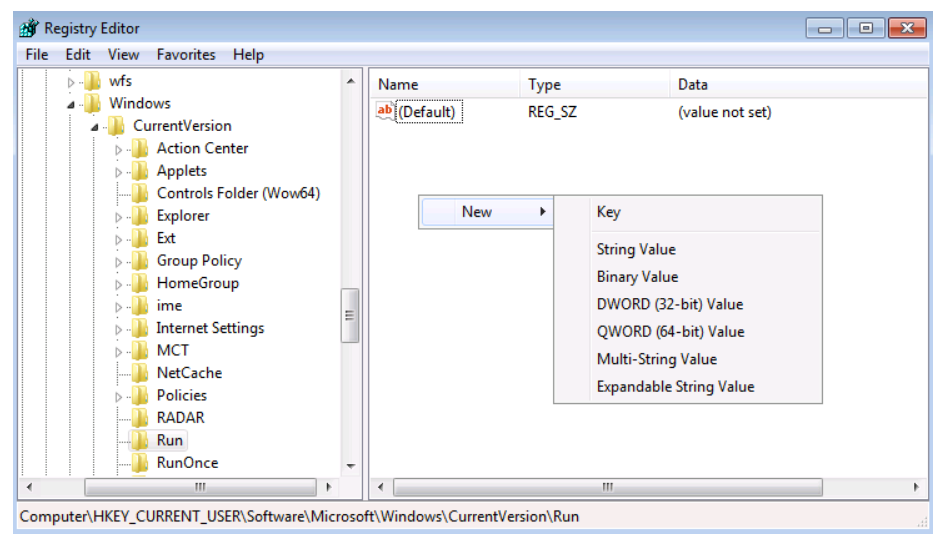

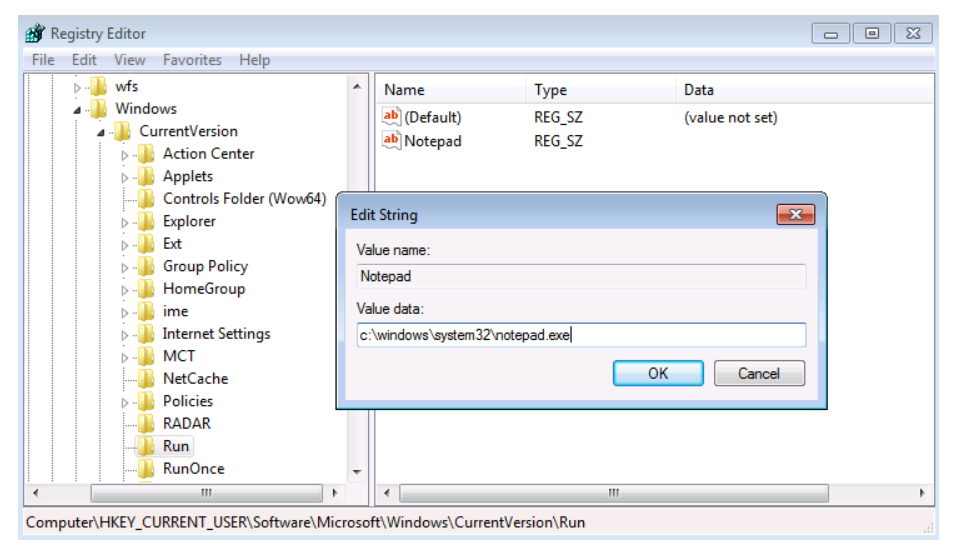

It is possible to manually edit the registry keys directly with the registry editor to control auto-start services, but if you edit something incorrectly or delete a key that is required by the system, you can damage a Windows system. Tools are available to view auto-start services and change their start-up properties without directly manipulating the registry. For example, the Msconfig.exe tool ships with the OS and allows you to view and edit system start-up properties. Access the tool by entering the msconfig command at the prompt, or in the search field of the start menu.

The Msconfig.exe tool allows you to control various aspects of the system configuration. Options are grouped as tabs in the following categories:

- General: This group of settings allows you to control various options for starting up the system. The default is a normal startup, but you can choose a diagnostic startup or a selective startup where you can control whether to start system services, startup items or whether to use the original boot configuration.

- Boot: If multiple versions of Windows are installed, you can choose which one to boot on startup. You also have options for controlling the safe boot mode, which is a boot process that is used for troubleshooting system issues. Safe boot mode is normally turned off to allow the system to perform a normal boot.

- Services: This section lists the services that are loaded in the system and their state: Stopped or Running. It also gives you the option to disable or enable the services, which will require a reboot to take effect.

- Startup: This section lists the applications and services that are configured to automatically start at boot time. It also gives you the option to disable or enable the applications and services to start at boot time, which will require a reboot to take effect.

- Tools: This section lists the tools that ship with the OS. You can launch the tools directly from this window.

System Shutdown

The best practice when halting a Windows system is to perform a proper shutdown, rather than simply turning it off. This gives the system a chance to terminate applications and services with dependencies in the proper order, and allows the system to write any configuration changes or pending edits to their respective files. Shutting down the system incorrectly can corrupt open files or damage applications that were in the process of doing something when the system was turned off.

Part of the shutdown process is to inform applications and services that a user requested a shutdown. The system communicates this request to each process so that the processes can start terminating open threads, and cleaning up open file handles. If a process thread does not respond within a predetermined period (default is 20 seconds), the system displays the hung application warning box, giving you the option to wait or close the application. After user mode applications have closed, the system begins terminating system processes. These processes are also bound by the timeout, however, no warning is displayed. The system may appear to hang at this point while it waits for the offending process to terminate. In this situation, after you have waited a reasonable period, you may have no choice but to manually turn off the system.

There are several ways to shut down a Windows system:

- From the Start menu: The Start menu configuration may differ slightly from one version of Windows to another, but you can always find it in the lower left portion of the screen. From there, you will see an option to shut down the system. Selecting that option presents a message box for you to select the type of shutdown to do.

- Ctrl+Alt+Delete: Affectionately known as the “three-finger salute” because this method requires the user to press the Ctrl, Alt, and Delete keys at the same time. A screen pops up with a series of options, including system shutdown. Note that the most recent versions of Windows eliminated this option from the list and replaced it with an icon in the lower right that brings up the list of shutdown options.

- Command line: Execute the shutdown command from the command line to begin the shutdown process. The command can take various parameters to determine the type of shutdown to perform.

There are three options for shutting down/restarting a Windows host:

- Shutdown: The OS completely shuts down.

- Restart: The OS completely shuts down and the system automatically re-boots.

- Sleep/hibernation: Captures system state and writes it to a file. The system then enters a low-power state but it is not completely turned off, allowing users to resume operation quickly without having to boot the host. The feature is primarily designed to accommodate laptop and mobile devices.

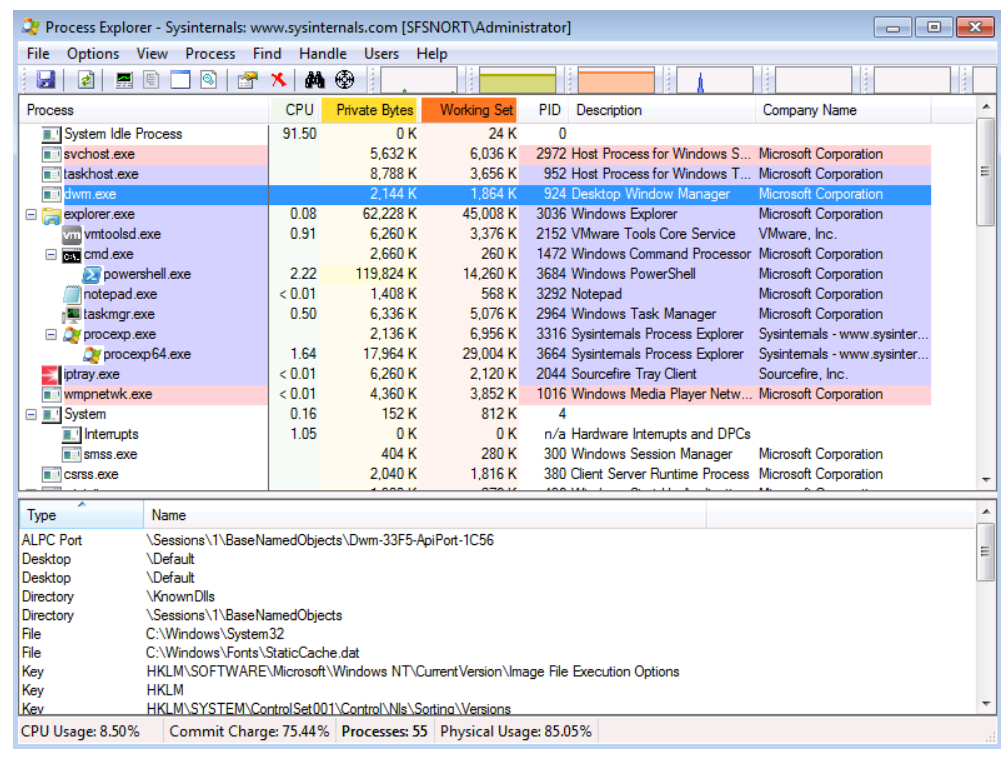

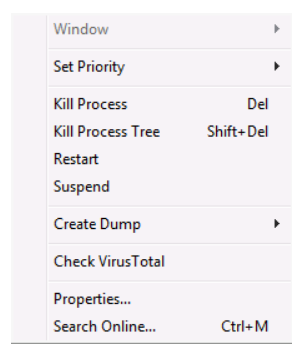

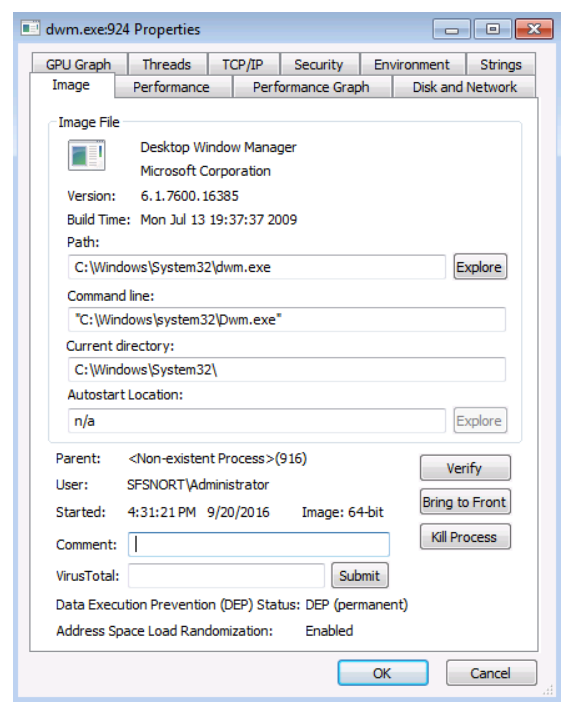

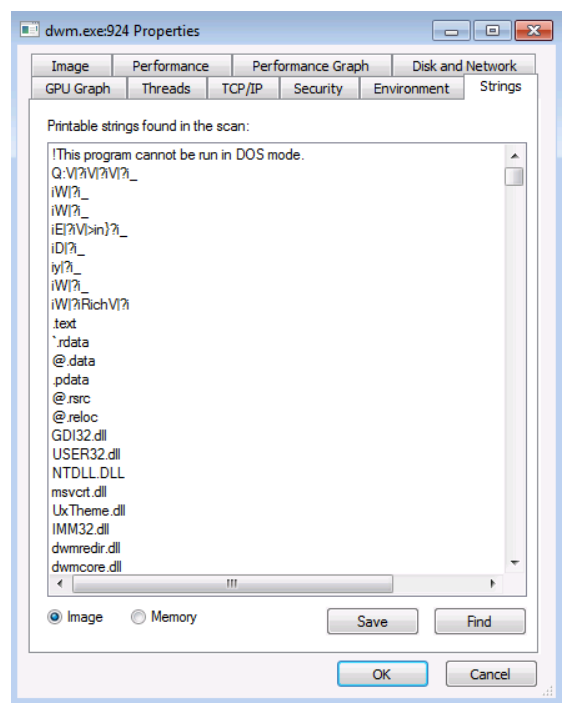

Controlling Services and Processes

When Windows is up and running, administrators need to know about the services and processes that are operating on a given host. This can be the result of simple system maintenance or it can be part of an investigation to see if there are suspicious processes that are running on a compromised host. This topic presents several tools that are available to get information about processes and manage them.

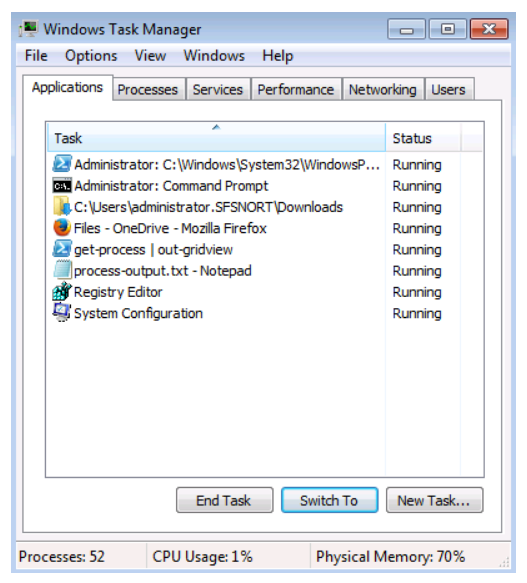

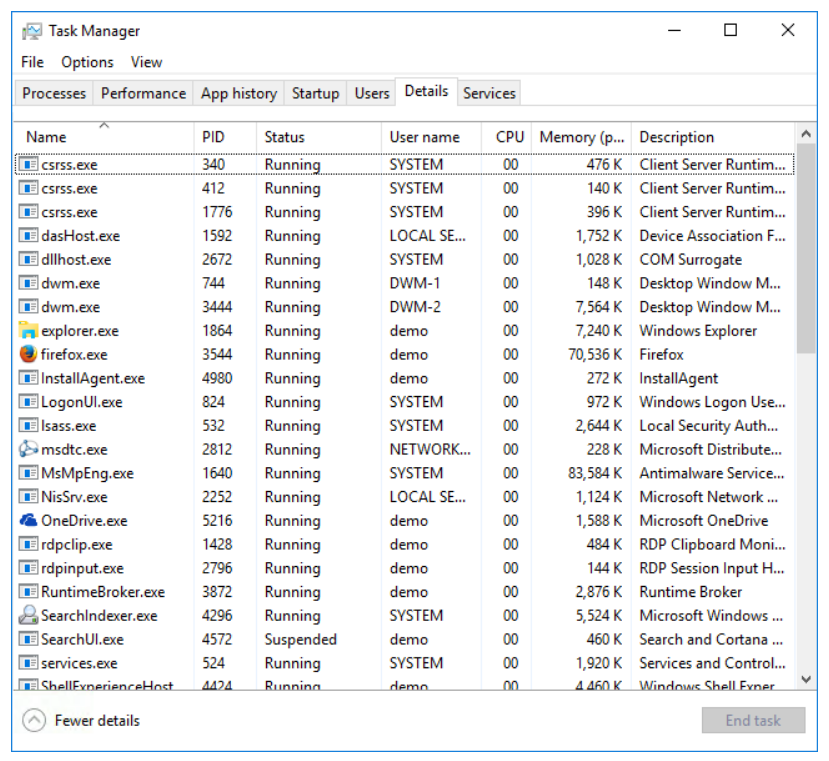

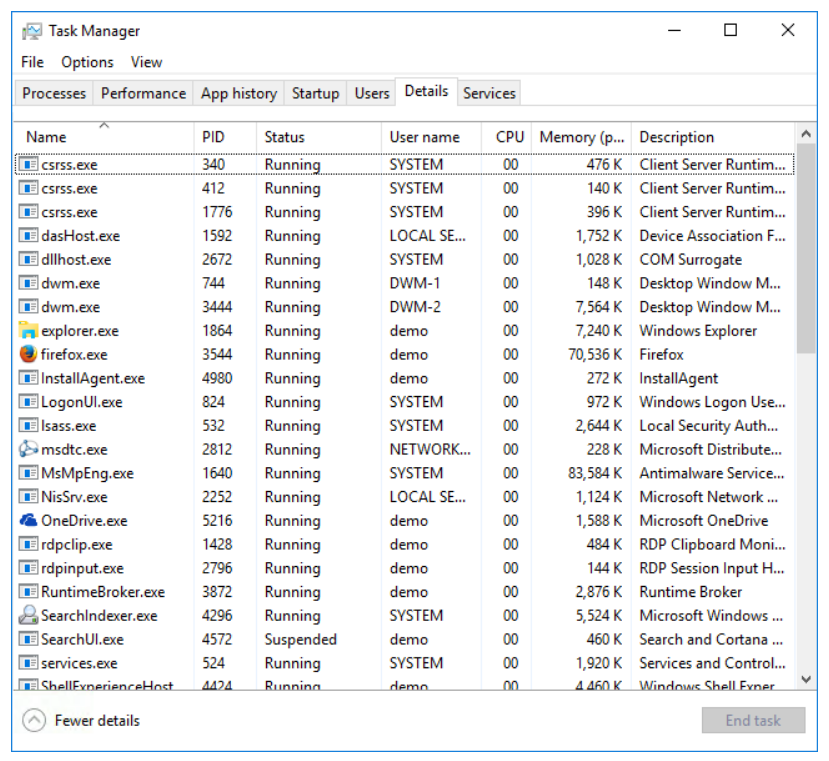

The task manager is a primary tool that every Windows administrator should be familiar with. The figure shows an example of the Task Manager window from a Windows 7 installation.

The task manager provides a great deal of information regarding what is running on the system including system performance metrics. Because it pertains to services and processes, the first three tabs provide the most useful information.

- Applications: Lists the applications currently running on the system and gives you the ability to end the task or switch to it. This area can be useful for killing hung applications.

- Right-clicking an application in this list gives you several options in a context menu. One of the interesting options you may find useful is to jump to the process that runs the application. - Processes: This tab lists processes running on the system and it also gives you the ability to sort applications several ways: by name, by the user that owns the process, by CPU resource consumption, by memory resource consumption and description. This view can help you identify processes consuming resources or acting strangely. You can also terminate misbehaving processes.

- Right-clicking a listed process opens a context menu for various things, such as opening the location of the file that starts the process or opening the processes properties. - Services: This tab provides a list of the services that are loaded on the system. It also shows you the service status: Running or Stopped. It also provides a button that opens the Services management console applet. From there, you have greater control over loaded services and configuring their properties.

- Right-clicking an item in the services list allows you to open a context menu with several options. For example, you can stop or start the service depending on its current state, and you can jump to the process that runs the service in the process list.

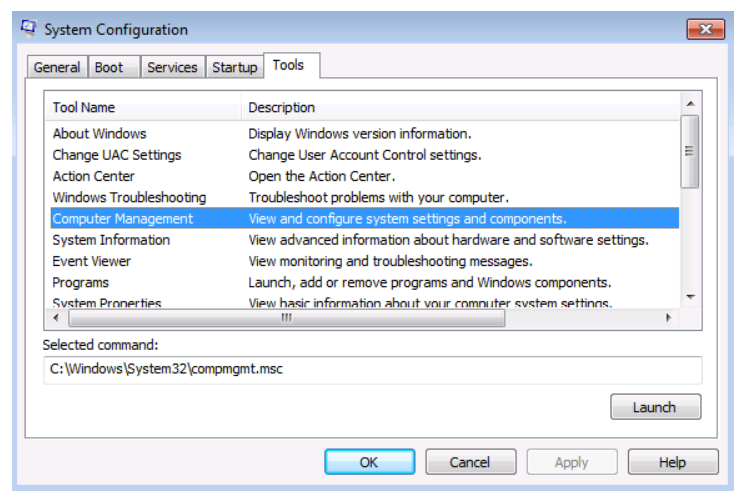

The msconfig utility also has the ability to show the status of the services. The figure below shows the Services tab of the msconfig utility.

The amount of management that you can perform from msconfig is somewhat limited: you can only enable or disable the services at the next reboot. But it allows you to view the services and potentially identify any that appear suspicious. You may also find useful tools to give you greater control through the Tools tab.

In the Tools tab, you can select a tool and launch it from this application window. In this example above, the user has selected the Computer Management tool which gives access to control a wide range of system settings, including services.

Evolution of Windows Task Manager

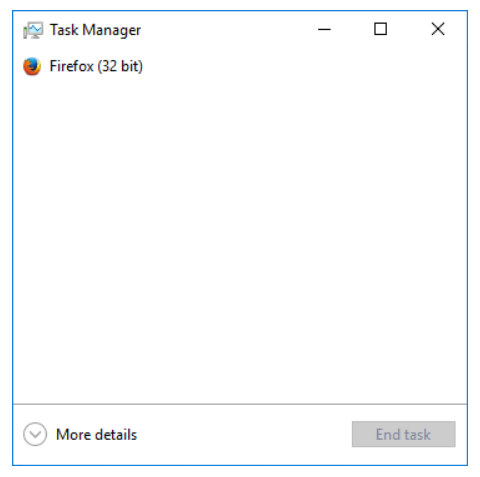

The task manager was updated in recent versions of Windows (version 8 or greater), and added some key enhancements and tabs that provide more useful information. This section provides an overview of the updated task manager.

First, the task manager opens as a simple window that lists applications that are currently running on the host.

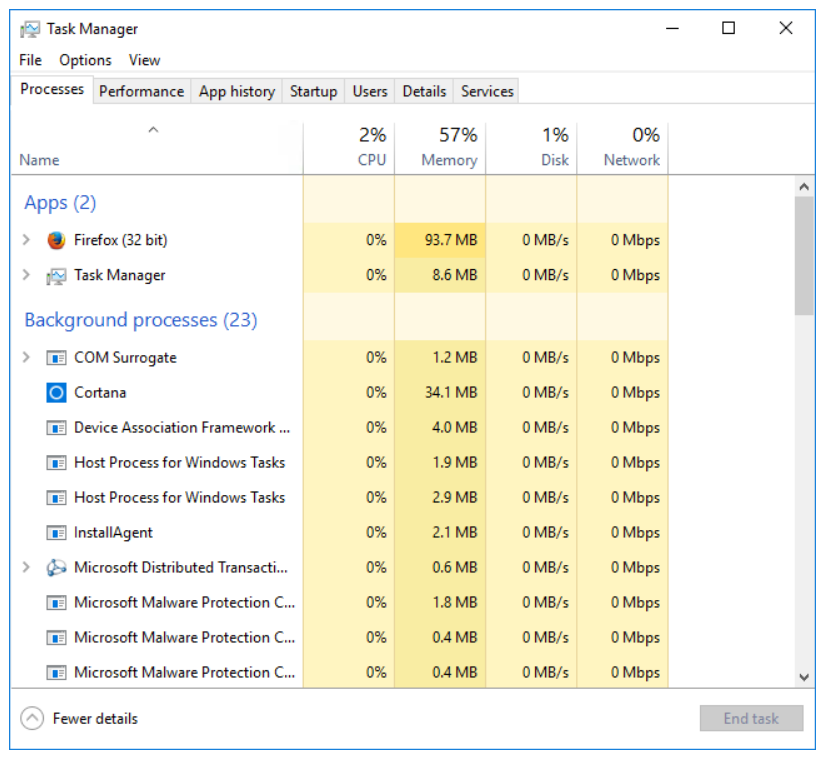

To get to all the task manager features, click the More Details button. This expands the window to reveal the full set of task manager features as seen in the figure below.

Note that the application tabs have changed and that the information is presented in a more graphically organized manner to improve what is presented at-a-glance.

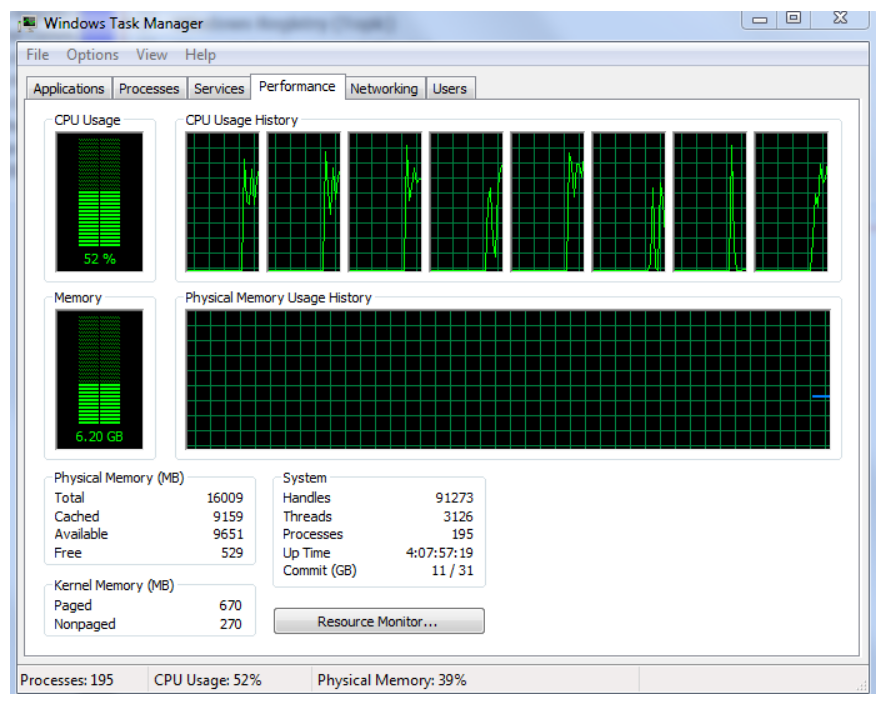

- Processes: This presentation includes both applications and processes in a single list. Applications and processes consuming large amounts of resources relative to others get shaded in various ways. Generally, the darker the shade of yellow and then orange, the higher the resource consumption. If resource utilization has reached a critical level, the value will be shaded in red. Processes are organized in terms of Background processes and Windows processes. Each section of the list is labeled accordingly.

- Another enhancement is that processes running sub-processes are identified with a button in the shape of a greater-than symbol. Clicking this button expands the selection to show the sub-processes. In the case of applications that are running multiple windows, such as a browser with multiple tabs open, clicking the button lists all the windows or tabs belonging to that instance of the application.

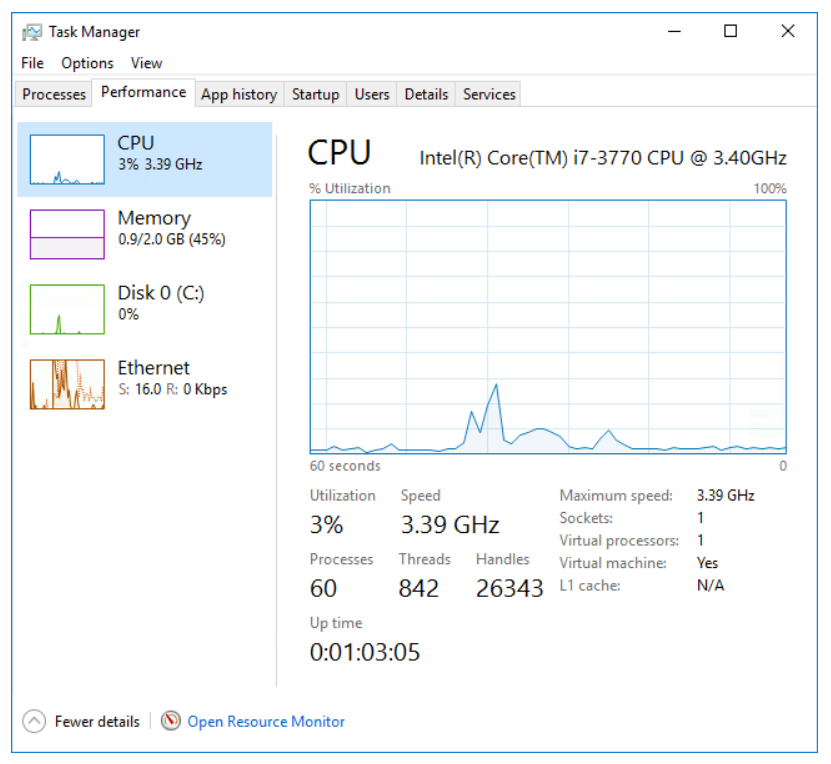

- One enhancement that could be particularly useful is embedded in the context menu. Right-click an application or process in the list to see a context menu that is associated with that item which contains an option that is called “Search Online.” This initiates a search for the item using the system’s default search engine. A key use case for this feature is to do a quick lookup on a process that is suspicious. However, be advised that many classes of malware either misrepresent what is displayed in the task manager or disable it all together. - Performance: This tab aggregates all the major performance metrics (CPU, memory, disk, and network) into a single section. You can click a resource in the left portion of the tab and the main panel populates with the performance details of that resource including a general performance graph over time and values of key metrics that are dynamically updated as resource consumption changes.

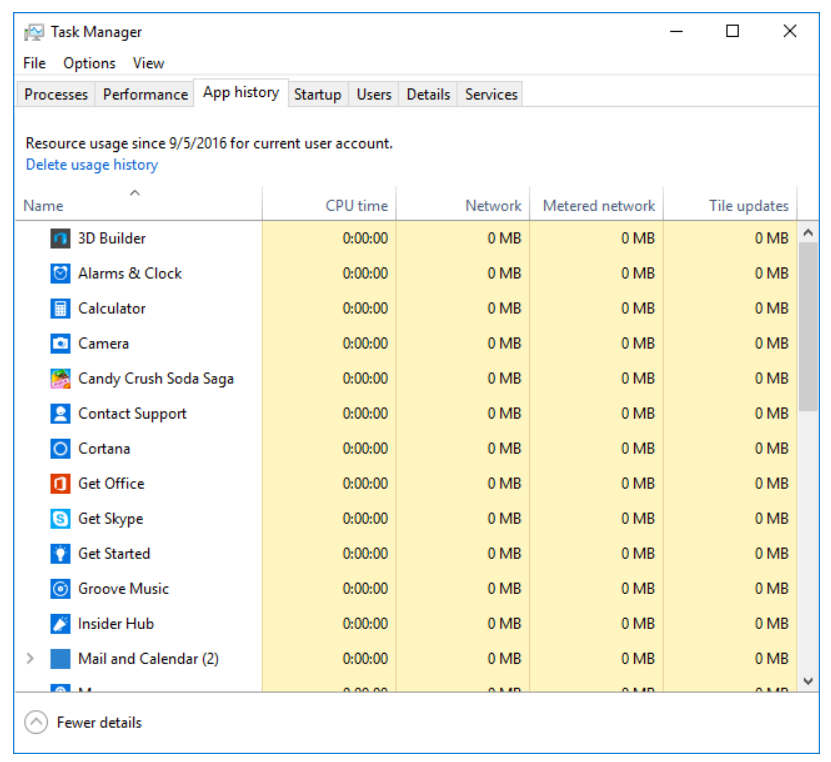

- App history: By default, this tab shows historical resource utilization of applications over time, giving you an idea of which applications may be consuming high amounts of resources. Edit the properties of this page to display historical resource consumption for all applications by clicking the Options menu at the top of the window.

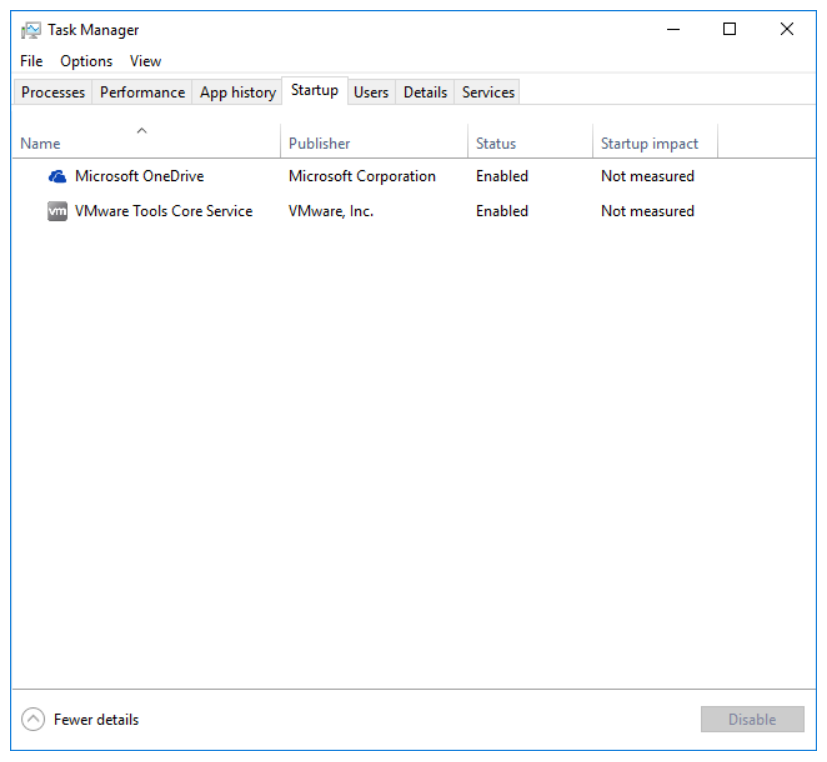

- Startup tab: This tab presents a list of applications and services that start up at boot time. You can select an item from this list and click the Disable button in the lower-right portion of the window to prevent the application from initializing at boot time.

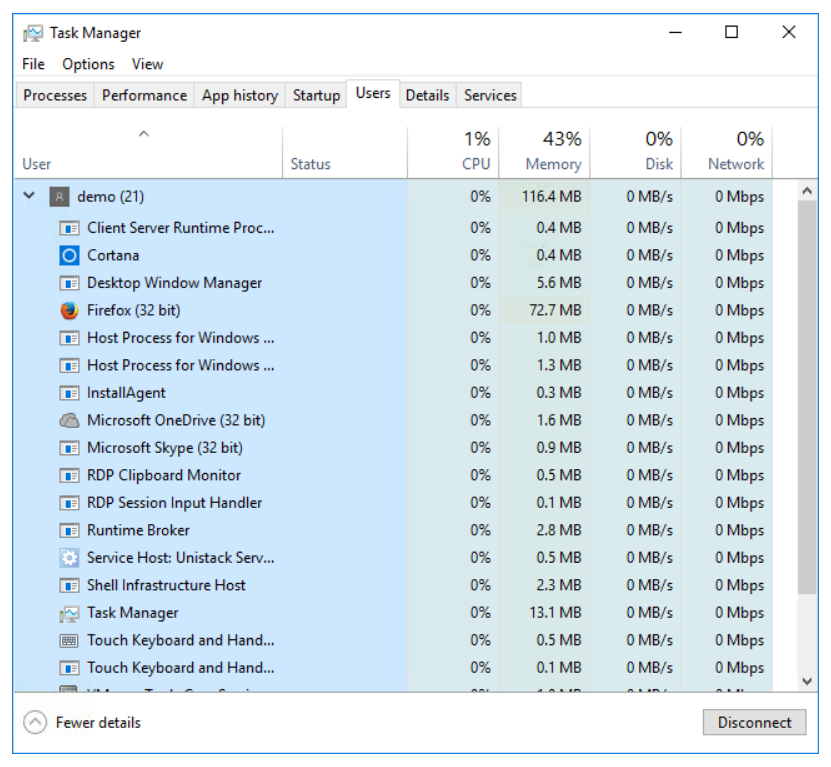

- Users tab: This tab displays users who are currently in the system. It also displays the resources that are consumed by the applications and processes that belong to each user. You can see a list of these processes by clicking the arrow button in front of the listed user to expose the list of processes belonging to the user. You can also select a user and disconnect him or her from the system if you have administrator privilege.

- Details tab: This tab displays a list of all the applications and processes running on the system. It expands on the capabilities of the Processes tab in that it displays status information for each item and it makes more advanced options for managing processes available through the context menu when you right-click an item. For example, it allows you to set a processing priority for an item. The context menu also allows you to set CPU affinity. Affinity is a feature that is used primarily on multi-core or multi-CPU systems, allowing a process to run on a specific core or CPU. Another option on the context menu is called, Analyze wait chain. This option will display the status of a process that might appear to be hung up. You can easily determine from this option whether a non-responsive application is waiting on another process.

- Services tab: This tab, as the name implies, lists the services that are loaded on the system and the service status (Running or Stopped). It is not much different than its predecessor from previous versions of Windows but it does include the ability to do an online search for a service that may not be familiar to you. It also allows you to open the Services applet from the management console application to give you greater control over the properties and configuration of services.

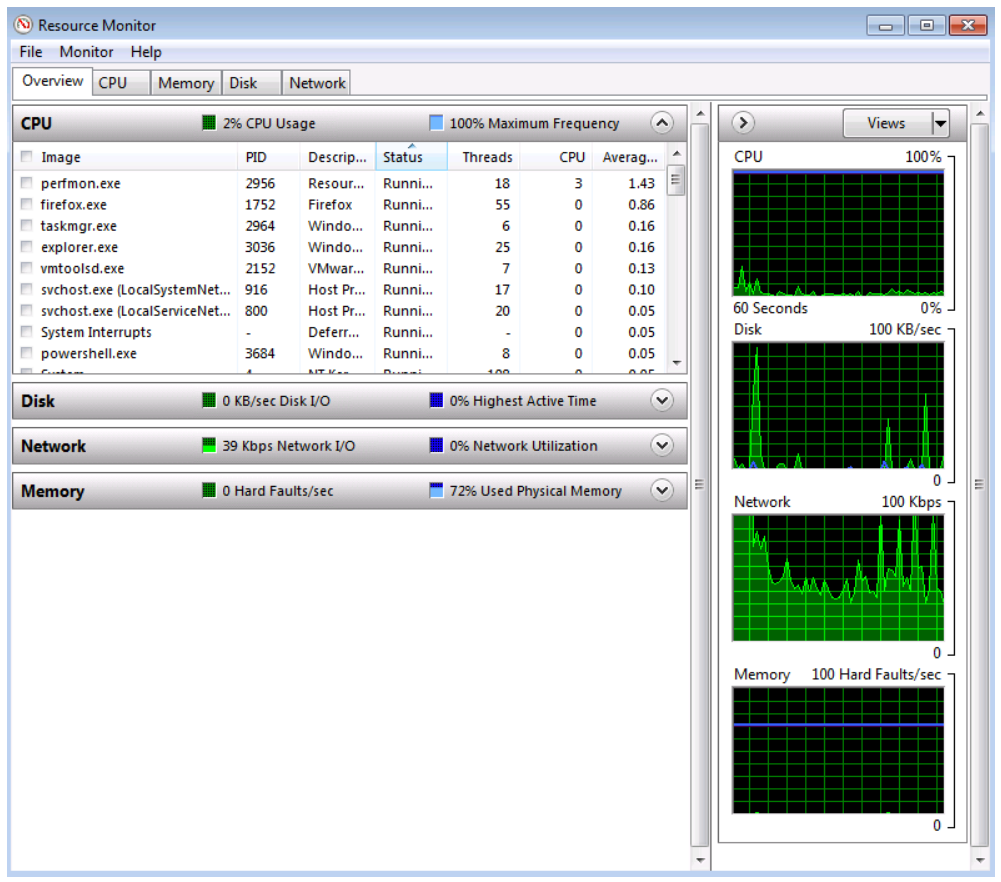

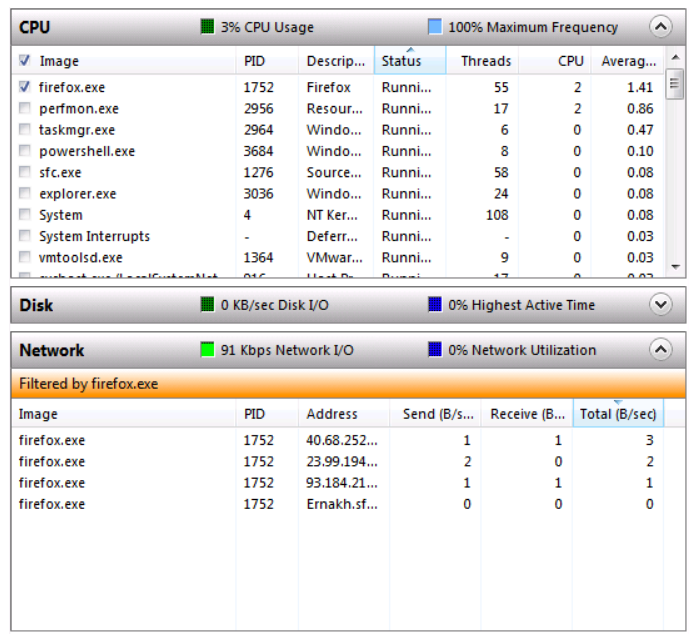

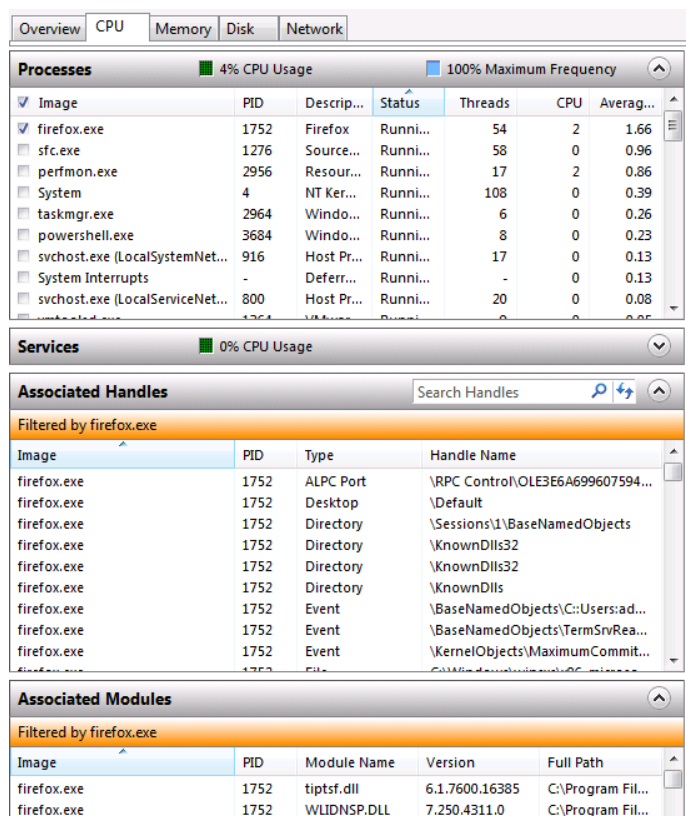

Monitoring System Resources

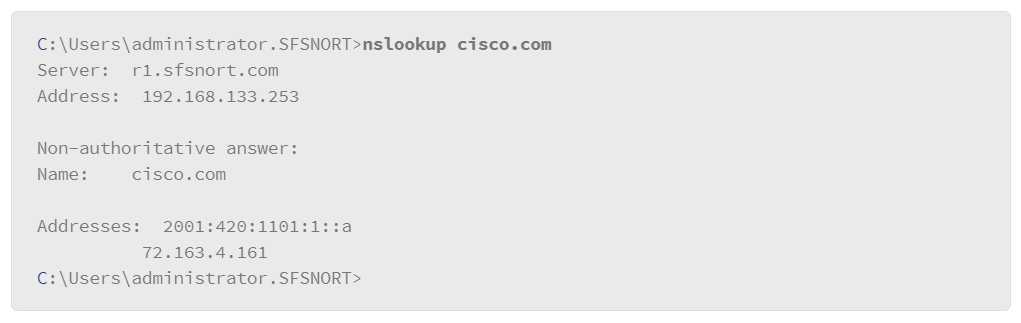

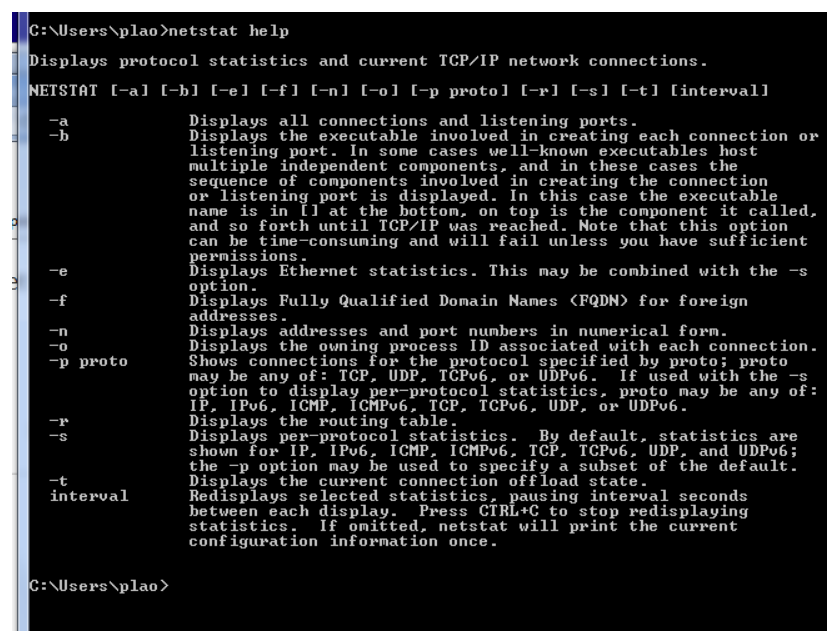

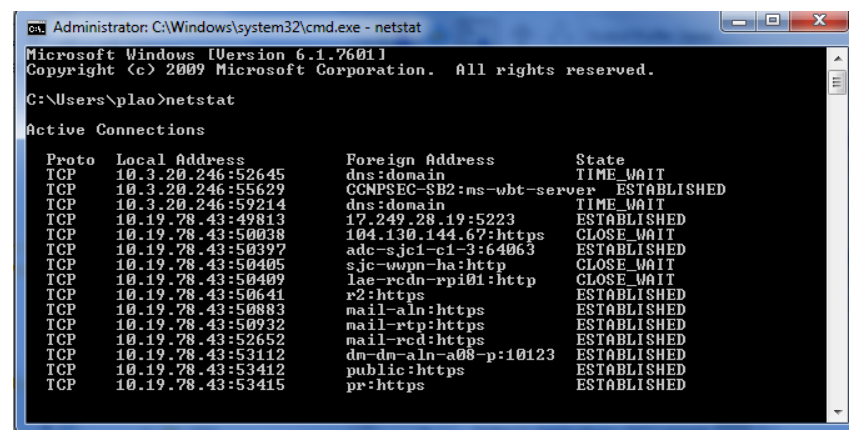

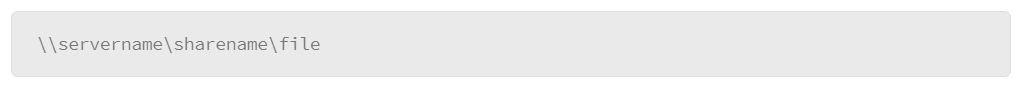

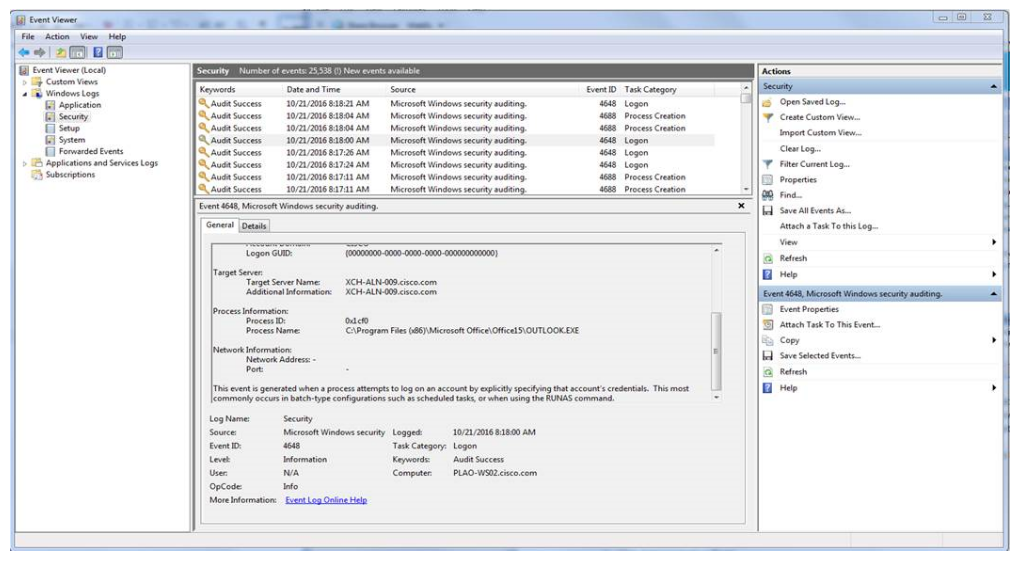

In addition to information that is related to services and applications that can be gathered from the Task Manager, you can also gather information that is related to system performance. Three Task Manager tabs provide information about various aspects of system performance: