Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 4: Understanding Basic Cryptography Concepts

4.2 Impact of Cryptography on Security Investigations

4.3 Cryptography Overview

4.4 Hash Algorithms

4.5 Encryption Overview

4.6 Cryptanalysis

4.7 Symmetric Encryption Algorithms

4.8 Asymmetric Encryption Algorithms

4.9 Diffie-Hellman Key Agreement

4.10 Use Case: SSH

4.11 Digital Signatures

4.12 PKI Overview

4.13 PKI Operations

4.14 Use Case: SSL/TLS

4.15 Cipher Suite

4.16 Key Management

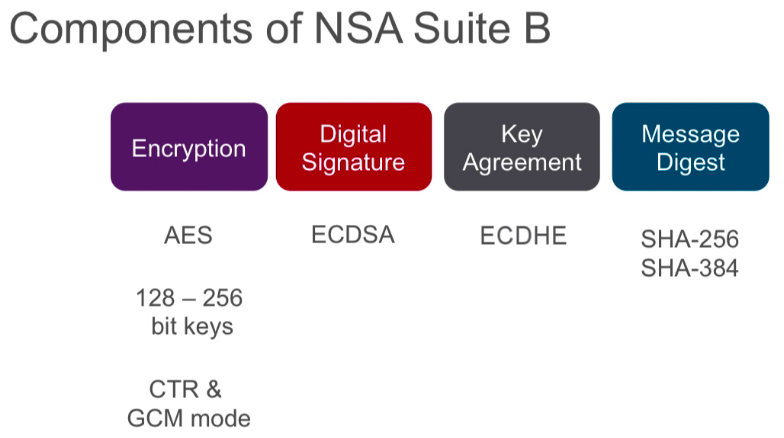

4.17 NSA Suite B

Impact of Cryptography on Security Investigations

Over the years, numerous cryptographic algorithms have been developed and used in many different protocols and functions. Cryptography is by no means static. Steady advances in computing and the science of cryptanalysis have made it necessary to continually adopt newer, stronger algorithms, and larger key sizes. The security analyst job role requires a good understanding of the different cryptographic algorithms and operations. The security analyst must be able to investigate security incidents involving the use of cryptography.

Security analysts must also continue their cryptography study to stay up-to-date on the latest cryptographic innovations. Furthermore, security analysts need to understand that attackers can attack the cryptographic algorithms, and they can use cryptography to hide their attacks.

A cryptographic attack is a method for circumventing the security of a cryptographic system by finding a weakness in the cryptographic algorithms. For example, in 2014, the OpenSSL Heartbleed vulnerability was assigned the common vulnerabilities and exposure ID CVE-2014-0160. This vulnerability leverages the implementation of the TLS heartbeat extension (RFC 6520) and the way an SSL enabled server validates heartbeat requests to provide a response. The vulnerability could allow an attacker that has crafted a heartbeat request with an improper length to receive responses that contain private data that is stored in the server memory.

Cryptography can also be used by attackers as an attack technology. For example, attackers can also use TLS/SSL encryption to hide their attack’s command and control traffic. Attackers use their command and control infrastructure to maintain communications with the compromised machines. TLS/SSL encryption makes the detection of the command and control communications very difficult. One detection method is to perform TLS/SSL decryption and inspection, and then run signatures that are based on detection over the decrypted traffic. Another method of detection is to perform traffic analysis using NetFlow to detect anomalous TLS/SSL flows. NetFlow will be discussed in a later section.

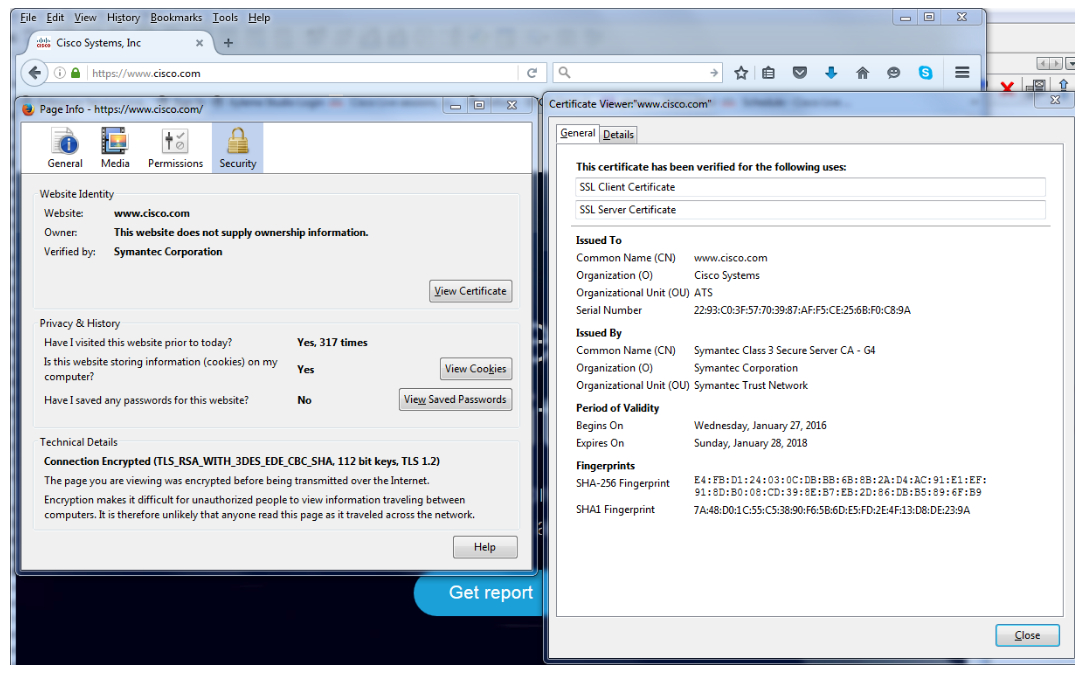

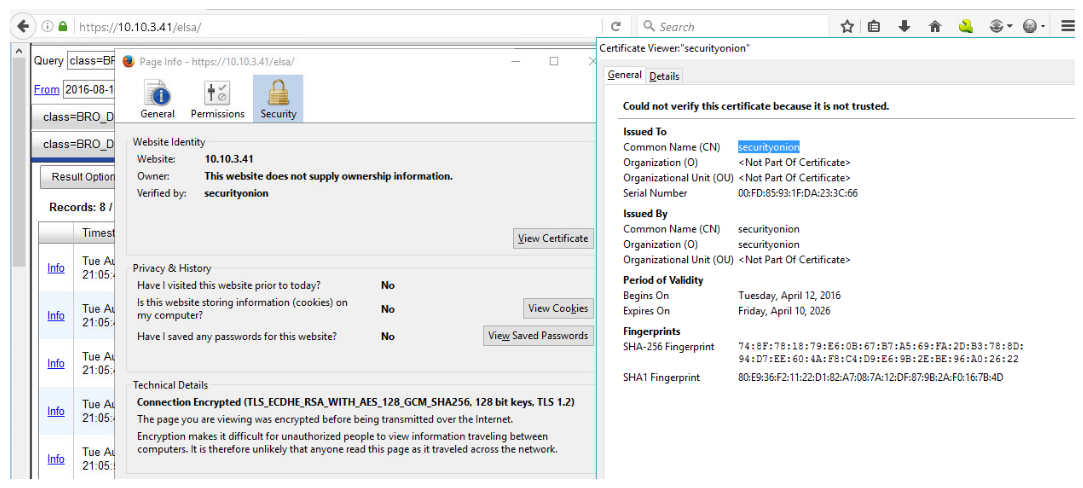

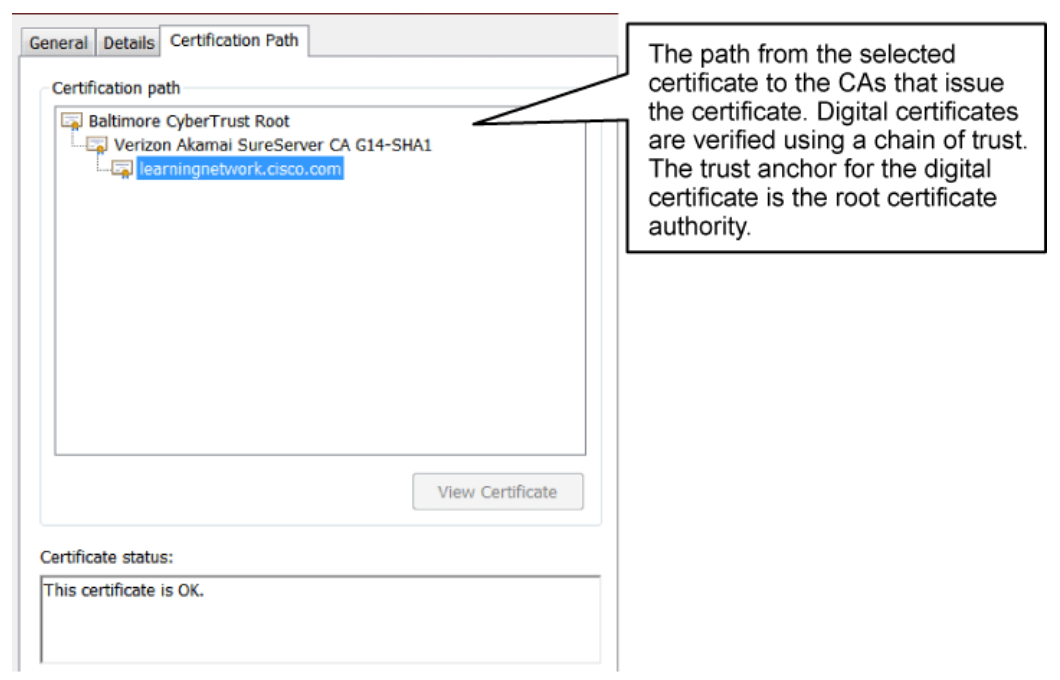

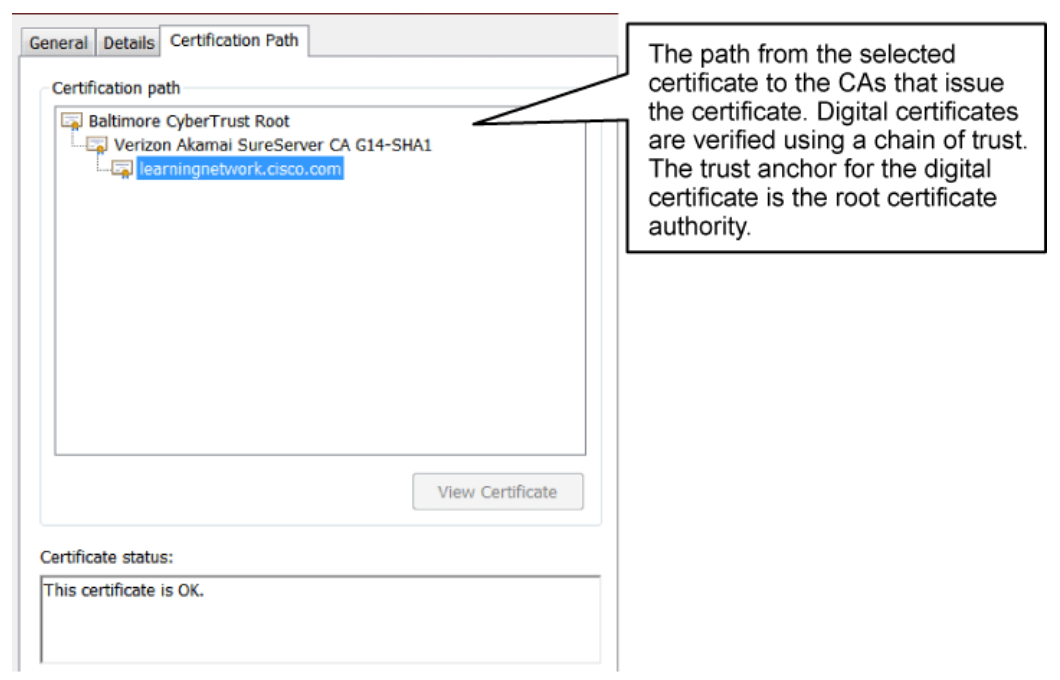

The example below illustrates one of the very basic skills that are required by the security analysts when investigating security incidents involving the use of digital certificates. A digital certificate contains a set of information about an entity. Explore the details of what’s in a digital certificate later on in this section.

The two figures below show two different digital certificates.

As the security analyst or even as an end user, one must be able to recognize the difference between these two digital certificates. The security analyst must be able to determine if the presented server’s digital certificate is valid or not.

The security analyst should be able to determine that the top one is a valid digital certificate that was issued to http://www.cisco.com by Symantec, and this digital certificate is valid until January 28, 2018. Symantec is the trusted third party that signed the digital certificate.

The security analyst should also be able to determine that the bottom one is an untrusted digital certificate because it is a self-signed digital certificate. The certificate was issued to security onion, and it was also issued by security onion.

Cryptography Overview

Cryptography is the practice and study of techniques to secure communications in the presence of third parties. Historically, cryptography was synonymous with encryption. Its goal was to keep messages private. In modern times, cryptography includes other responsibilities:

- Confidentiality: Ensuring that only authorized parties can read a message

- Data integrity: Ensuring that any changes to data in transit will be detected and rejected

- Origin authentication: Ensuring that any messages received were actually sent from the perceived origin

- Non-repudiation: Ensuring that the original source of a secured message cannot deny having produced the message

Cryptanalysis is the practice and study of determining and exploiting weakness in cryptographic techniques. Cryptology is an umbrella term which covers both cryptography and cryptanalysis. There is a symbiotic relationship between the two disciplines, because each improves the other one. National security organizations employ members of both disciplines and put them to work against each other.

At times, one discipline has been further along than the other. For example, during the Hundred Years’ War between France and England, the cryptanalysts were ahead of the cryptographers. France believed that the Vigenère cipher was unbreakable; however, the British were able to break it. Some historians believe that World War II largely turned on the fact that the winning side on both fronts was much more successful than the losing side was at cracking the encryption of its adversary. Currently, it is believed that cryptographers are further along than cryptanalysts.

It is an ironic fact of cryptography that it is impossible to prove that an algorithm is secure. You can prove only that it is not vulnerable to known cryptanalytic attacks. If there are methods that have been developed but are unknown to the cryptographers, then an algorithm may be able to be cracked. You can prove only invulnerability to known attacks, except for a brute-force attack.

All algorithms are vulnerable to brute force. If every possible key is tried, one of the keys has to work. Therefore, no algorithm is unbreakable. The best you can hope for are algorithms that are vulnerable only to brute-force attacks.

Cryptography History

Cryptography began in diplomatic circles thousands of years ago. Messengers from the court of a ruler would take encrypted messages to other courts. Occasionally, other courts that were not involved in the communication would attempt to steal any message that was sent to a rival kingdom. Encryption was first used for this purpose.

Not long after, military commanders started using encryption to secure messages. These messengers faced greater challenges than the diplomatic messenger faced, because killing the messenger to get the message was very common. With such high stakes involved, military commanders used encryption to secure their military communications.

There are many famous ciphers from history. The cipher that is attributed to Julius Caesar was a simple substitution cipher that was used on the battlefield to quickly encrypt messages that could easily be decrypted by field commanders. Thomas Jefferson, the third president of the United States, was a man of many interests. Among his many inventions was an encryption system that was likely used when serving as Secretary of State from 1790 to 1793.

In 1918, Arthur Scherbius invented a machine that served as a template for the machines that all the major participants in World War II used. He called the machine Enigma and sold it to Germany, estimating that if 1000 cryptanalysts tested four keys per minute, all day, every day, it would take 1.8 billion years to try them all.

During World War II, both the axis and Allies had machines that were modeled after the Scherbius machine. These machines were the most sophisticated encryption devices that had been developed then. In response to those machines, the British arguably invented the first computer in the world, the Colossus, to break the encryption that was used by the Enigma.

Ciphers for Everyone

A cipher is an algorithm for performing encryption and decryption. Ciphers are a series of well-defined steps that you can follow as a procedure. Different types of ciphers have proven useful historically.

- Substitution ciphers: Substitution ciphers substitute one letter for another. In their simplest form, substitution ciphers retain the letter frequency of the original message. The cipher that was attributed to Julius Caesar was a substitution cipher. Every day was assigned a different key, and that key was used to adjust the alphabet accordingly. For example, if the key for a certain day was five, then an “A” was moved five letters ahead in the alphabet, resulting in an encoded message that used “F” in place of “A.” “B” was then “G,” “C” was “H,” and so on. The next day, the key might be eight, and the process would begin again with “A” now becoming “I,” “B” becoming “J,” and so on.

One of the drawbacks of substitution ciphers is that if the message is long enough, it may be vulnerable to what is called “frequency analysis,” because it retains the frequency patterns of letters that are found in the original message. Because of this weakness, polyalphabetic ciphers were invented. - Polyalphabetic ciphers: Polyalphabetic ciphers are based on substitution, using multiple substitution alphabets. The famous Vigenère cipher is an example. That cipher uses a series of different Caesar ciphers that are based on the letters of a keyword. It is a simple form of polyalphabetic substitution and is therefore invulnerable to frequency analysis.

To illustrate how this type of cipher works, suppose that a key of “SECRETKEY” is used to encode “ATTACK AT DAWN.” The “A” is encoded by looking at the row starting with “S” for the letter in the “A” column. In this case, the “A” is replaced with “S.” Then you look for the row that begins with “E” for the letter “T,” resulting in “X” as the second character. If you continue this encoding method, the message “ATTACK AT DAWN” is encrypted as “SXVRGDKXBSAP.” - Transposition ciphers: Transposition ciphers rearrange or permutate letters, instead of replacing them. Transposition is also known as permutation. An example of this type of cipher takes the message “THE PACKAGE IS DELIVERED” and transposes it to read “DEREVILEDSIEGAKCAPEHT.” In this example, the key is to reverse the letters. The Rail Fence Cipher is a transposition cipher in which the words are spelled out as if they are a rail fence. Each subsequent letter of the text is written downwards and diagonally on successive "rails" of an imaginary fence until the bottom rail is reached. At that point, each subsequent letter is written upwards and diagonally until the top rail is reached, and so on. The number of rails used is the cipher key. The example below illustrates a key of three.

Note: In order to read the message, simply read diagonally up and down, following the rail fence. You will find that the message "THE COVER IS BLOWN FLEE AT ONCE" has been encoded as "TOIOLTEHCVRSLWFEAOCEEBNEN."

Some modern algorithms, such as DES and 3DES, still use transposition as part of the algorithm. - One-time pad: The one-time pad was invented and patented by Gilbert Vernam in 1917 while working at AT&T. A one-time pad is also known as a Vernam cipher. Vernam's idea was a stream cipher that would apply the XOR operation to plaintext with a key. Joseph Mauborgne, a captain in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, contributed the idea of using random data as a key. This combined idea is so significant that the NSA has called this patent “perhaps the most important in the history of cryptography.”

There are several difficulties inherent in using one-time pads in the real world. The first is the challenge of creating random data. Computers, because they have a mathematical foundation, are incapable of creating truly random data. Also, if the key is used more than once, it is trivial to break. Key distribution is also challenging.

Hash Algorithms

Hashing is a mechanism that is used for data integrity assurance. Hashing is based on a one-way mathematical function: functions that are relatively easy to compute, but significantly difficult to reverse. Grinding coffee is a good example of a one-way function: It is easy to grind coffee beans, but it is almost impossible to put back all the tiny pieces together to rebuild the original beans.

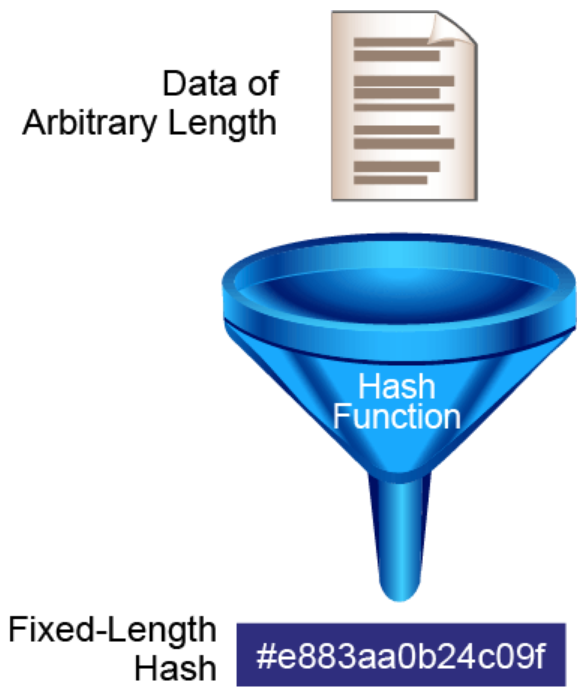

The figure below illustrates how hashing is performed. Data of an arbitrary length is input into the hash function, and the result of the hash function is the fixed-length hash, which is known as the “digest” or “fingerprint.” When the same data is passed through a hash algorithm twice, the output is identical. Any small modification to the data produces an entirely different output. This characteristic is often referred to as the avalanche effect. Data is deemed to be authentic if running the data through the hash algorithm produces the expected fingerprint. Since hash algorithms produce a fixed-length output, there are a finite number of possible outputs. It is possible for two different inputs to produce an identical output. They are referred to as hash collisions.

Hashing is similar to the calculation of CRC checksums, but it is much stronger cryptographically. CRCs were designed to detect randomly occurring errors in digital data where hash algorithms were designed to assure data integrity even when data modifications are intentional with the objective to pass fraudulent data as authentic. One primary distinction is the size of the digest produced. CRC checksums are relatively small, often 32 bits. Commonly used hash algorithms produce digests in the range of 128 to 512 bits in length. It is relatively easier for an attacker to find two inputs with identical 32-bit checksum values than it is to find two inputs with identical digests of 128 to 512 bits in length.

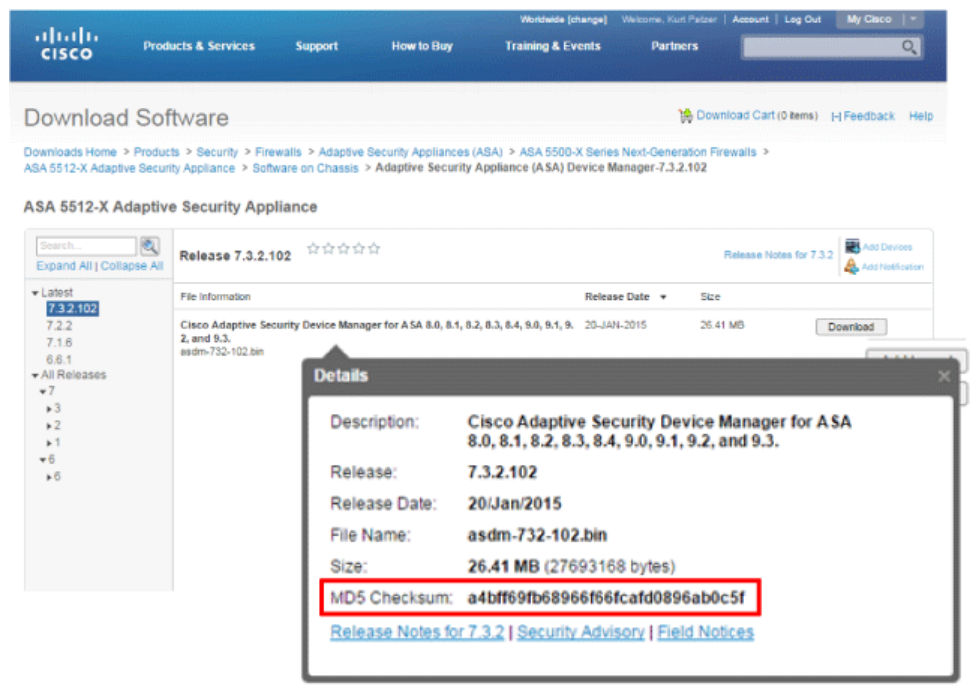

The figure below shows one use of hash algorithms to provide data integrity. Organizations that offer software for download often publish hash digests on the download page that can be used to verify data integrity of the downloaded software.

Cryptographic Authentication Using Hash Technology

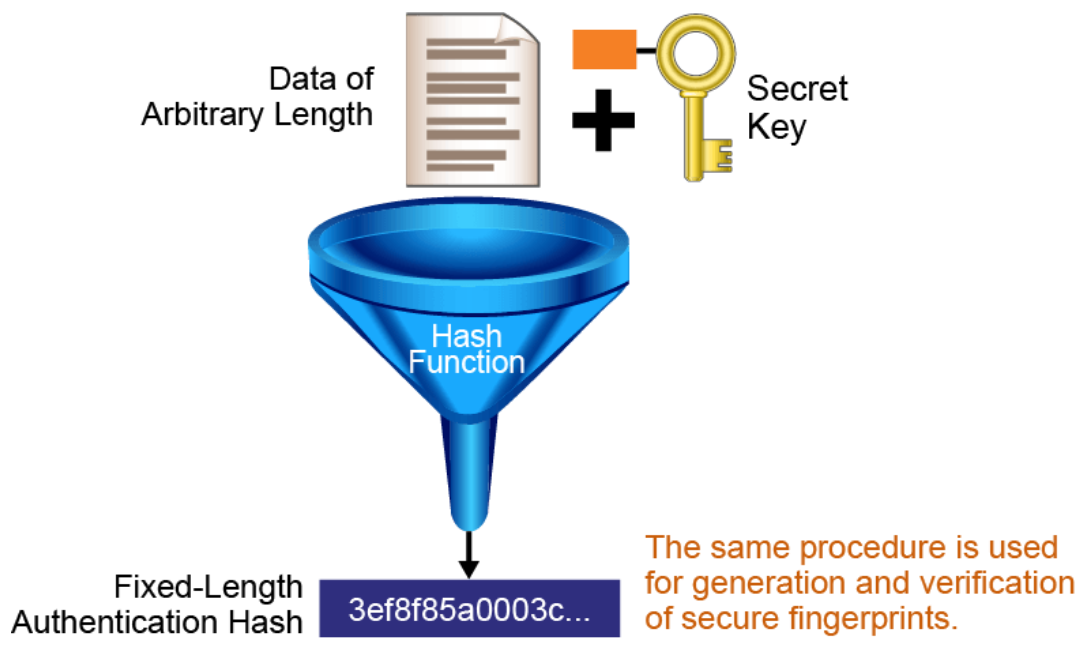

Two systems that have agreed on a secret key can use the key along with a hash function to verify data integrity of communication between them by using a keyed hash. A message authentication code is produced by passing the message data along with the secret key through a hash algorithm. Only the sender and the receiver know the secret key, and the output of the hash function now depends on the message data and the secret key. Therefore, only parties who have access to that secret key can compute the appropriate hash digest. This behavior defeats man-in-the-middle attacks and provides authentication of the data origin. If two parties share a secret key and use hash technology for authentication, receipt of a properly constructed message authentication code indicates that the other party was the originator of the message, because it is the only other entity possessing the secret key.

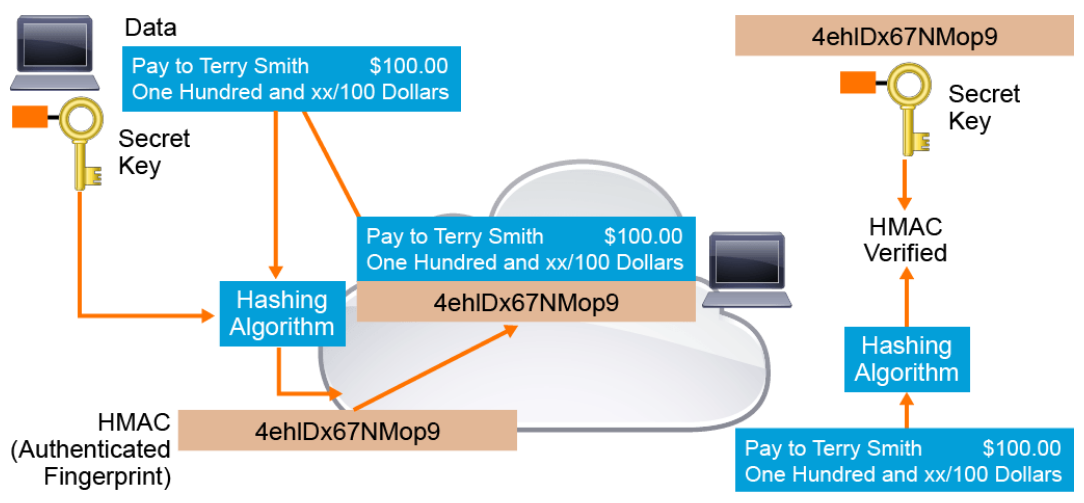

The figure below illustrates how the message authentication code is created. Data of an arbitrary length is input into the hash function, together with a secret key. The result is the fixed-length hash that depends on the data and the secret key.

Note:

RFC 2104 describes a particularly strong hash-based cryptographic authentication mechanism called HMAC (Hashed Message Authentication Code). The HMAC algorithm actually performs two nested hash computations of the message data, key, and padding material processed with Boolean logic. The HMAC algorithm is used for data integrity by IPsec.

Cryptographic Authentication in Action

The figure below illustrates cryptographic authentication in action. The sender wants to ensure that the message is not altered in transit and wants to provide a way for the receiver to authenticate the origin of the message.

The sending device inputs data and the secret key into the hashing algorithm and calculates the fixed-length message authentication code, or fingerprint. This authenticated fingerprint is then attached to the message and sent to the receiver. The receiving device removes the fingerprint from the message and uses the received message with its copy of the secret key as input to the same hashing function. If the fingerprint that is calculated is identical to the fingerprint that was received, then data integrity has been verified. Also, the origin of the message is authenticated, because only the sender possesses a copy of the shared secret key. The keyed hash function has ensured the authenticity of the message.

Cisco products use hashing for entity authentication, data integrity, and data authenticity purposes:

- IPsec gateways and clients use hashing algorithms to verify packet integrity and authenticity. The algorithm, which is defined in RFC 2104, is more complex than a simple keyed hash and uses two hash computations to produce the message authentication code.

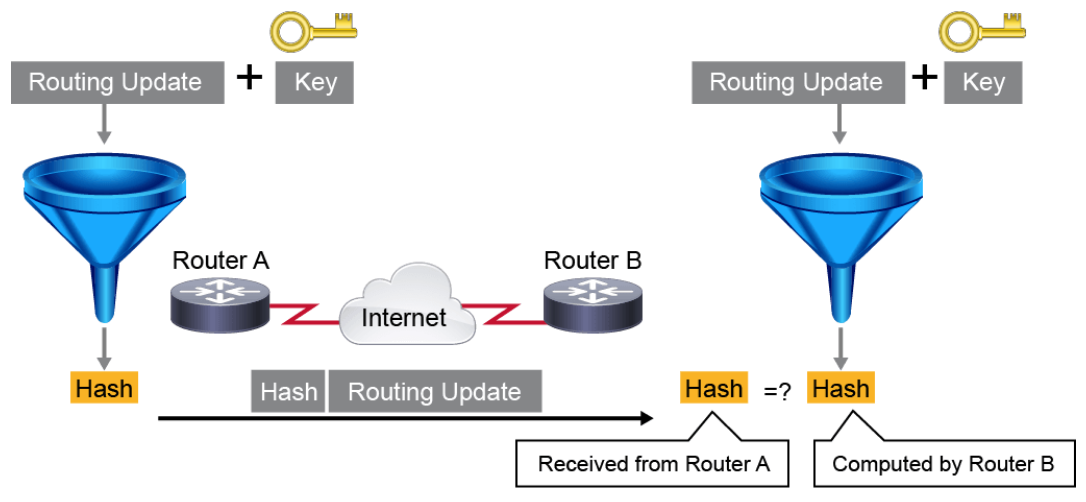

- Cisco IOS routers use keyed hashing with secret keys to add authentication information to routing protocol updates.

- Cisco software images that you can download from Cisco.com have an MD5-based checksum that is available, so that customers can check the integrity of downloaded images.

- Hashing can also be used in a feedback-like mode to encrypt data. For example, TACACS+ uses MD5 to encrypt its session.

The figure below shows how route authentication occurs on Cisco routers. Route authentication using a keyed hash allows the validation of route integrity. If the route information is tampered with during transit, the receiving router upon calculating the keyed hash finds the computed hash to be different from the received hash. Even if an attacker intercepts the route information and injects a new hash after changing the route information, the attempt fails, because the attacker does not know the secret key. Without the secret key, the attacker cannot produce a message authentication code that will be accepted by the receiver.

Note:

You can configure neighbor authentication for the following routing protocols: BGP, IS-IS, EIGRP, OSPF, and RIPv2.

This technique is only as strong as the secret key. If the attacker knows the secret key, they can generate a malicious routing update and the appropriate keyed hash that will be accepted by the peer routers. Also note that this technique does not provide privacy. While it prevents an attacker from manipulating a routing update that they intercept, it does not prevent the attacker from reading the routing update.

Comparing Hashing Algorithms

The three most commonly used cryptographic hash functions are MD5, SHA-1, and SHA-2.

The MD5 algorithm is a ubiquitous hashing algorithm that was developed by Ron Rivest. Although MD5 is used in various Internet applications today, it is not recommended for new applications.

MD5 is a one-way function that makes it easy to compute a hash from the given input data, but makes it unfeasible to compute the original input data that are given only a hash. MD5 is essentially a complex sequence of simple binary operations, such as XORs and rotations, that is performed on input data and produces a 128-bit digest. MD5 was originally thought to be collision-resistant, but has been shown to have collision vulnerabilities.

Note:

Collision-resistant means that two messages with the same hash are very unlikely to occur.

The main algorithm itself is based on a compression function, which operates on blocks. The input is a data block, plus feedback of previous blocks. The 512-bit blocks are divided into sixteen 32-bit subblocks. These blocks are then rearranged with simple operations in a main loop, which consists of four rounds. The output of the algorithm is a set of four 32-bit blocks, which concatenate to form a single 128-bit hash value. The message length is also encoded into the digest.

The U.S. NIST developed SHA, the algorithm that is specified in the Secure Hash Standard (SHS). SHA-1 is a revision to SHA that was published in 1994. The revision corrected an unpublished flaw in SHA. Its design is very similar to the Message Digest 4 (MD4) family of hash functions that Ron Rivest developed.

The SHA-1 algorithm takes a message of up to 2^64 bits in length and produces a 160-bit message digest. The algorithm is slightly slower than MD5, but the larger message digest makes it more secure against brute-force collision and inversion attacks.

Secure Hash Algorithm 2 (SHA-2) specifies six SHAs—SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, SHA-512/224 and SHA-512/256. When a message of any length up to 2^64 bits (for SHA-224 and SHA-256) or up to 2^128 bits (for SHA-384 and SHA-512) is input to an SHA-2 algorithm, the result is a message digest that ranges in length from 224 to 512 bits, depending on the algorithm. SHA-512 is actually more efficient to implement than SHA-256 on 64-bit computational systems. SHA-512/224 and SHA-512/256 are based on the SHA-512 algorithm, modifying the internal initialization vector and truncating the digest output to 224 bits and 256 bits respectively. They were introduced to allow the use of the SHA-512 algorithm in situations where it is faster than SHA-256 but a smaller digest size is desirable.

The SHA-2 family of hash functions was approved by NIST for use by federal agencies in 2006, for all applications using SHAs. The publication encouraged all federal agencies to stop using SHA-1 for digital signatures, digital time stamping, and other applications that require collision resistance when practical, and it mandated the use of the SHA-2 family of hash functions for these applications after 2010. After 2010, federal agencies used SHA-1 only for the following applications: HMACs, key derivation functions (KDFs), and random number generators (RNGs). This change was triggered in 2005, when security flaws were identified for SHA-1 in theoretical exploits that exposed weakness to collision attacks.

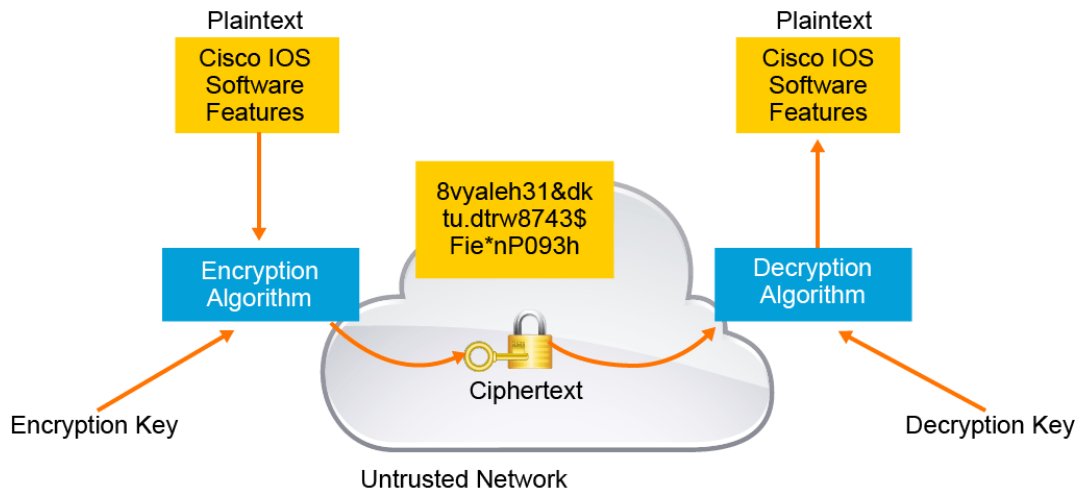

Encryption Overview

Encryption is the process of disguising a message in such a way as to hide its original contents. With encryption, the plaintext readable message is converted to ciphertext, which is the unreadable, “disguised” message. Decryption reverses this process. Encryption is used to guarantee confidentiality so that only authorized entities can read the original message.

Old encryption methods, such as the Caesar cipher, were based on the secrecy of the algorithm to achieve confidentiality. It is difficult to maintain the secrecy of an encryption algorithm, and it is difficult to devise new secret encryption algorithms to replace ones which are no longer secret. Modern encryption relies on public algorithms that are cryptographically strong using secret keys. It is much easier to change keys than it is to change algorithms. In fact, most cryptographic systems dynamically generate new keys over time, limiting the amount of data that may be compromised with the loss of a single key.

Encryption can provide confidentiality at various layers of the OSI model, such as the following:

- Encrypt application layer data, such as encrypting email messages with PGP (Pretty Good Privacy).

- Encrypt session layer data using a protocol such as SSL or TLS.

- Encrypt network layer data using protocols such as those provided in the IPsec protocol suite.

- Encrypt data link layer using MACsec (IEEE 802.1AE) or proprietary link-encrypting devices.

Encryption Algorithm Features

A good cryptographic algorithm is designed in such a way that it resists common cryptographic attacks. The best way to break data that is protected by the algorithm is to try to decrypt the data using all possible keys. The amount of time that such an attack needs depends on the number of possible keys, but the time is generally very long. With appropriately long keys, such attacks are usually considered unfeasible.

Variable key lengths and scalability are also desirable attributes of a good encryption algorithm. The longer the encryption key is, the longer it takes an attacker to break it. For example, a 16-bit key means that there are 65,536 possible keys, but a 56-bit key means that there are 7.2 x 10^16 possible keys. Scalability provides flexible key length and allows you to select the strength and speed of encryption that you need.

Changing only a few bits of the plaintext message causes its ciphertext to change completely, which is known as an avalanche effect. The avalanche effect is a desired feature of an encryption algorithm, because it allows very similar messages to be sent over an untrusted medium, with the encrypted (ciphertext) messages being completely different.

You must carefully consider export and import restrictions when you use encryption internationally. Some countries do not allow the export of encryption algorithms, or they allow only the export of those algorithms with shorter keys. Some countries impose import restrictions on cryptographic algorithms.

In January 2000, the restrictions that the U.S. Department of Commerce placed on export regulations were dramatically relaxed. Currently, any cryptographic product is exportable under a license exception, unless the end users are governments outside of the United States or are embargoed.

Encryption Algorithms and Keys

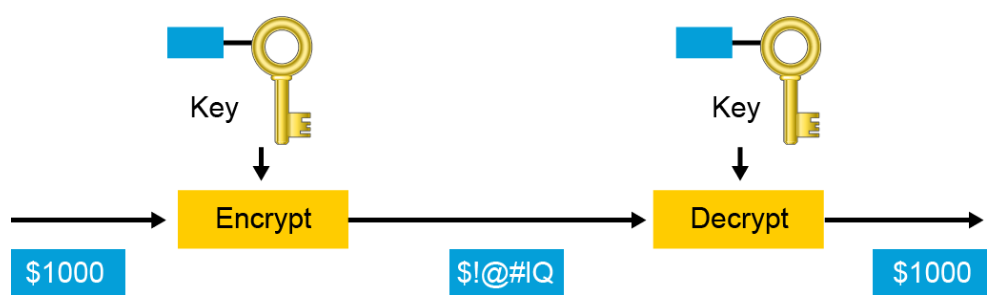

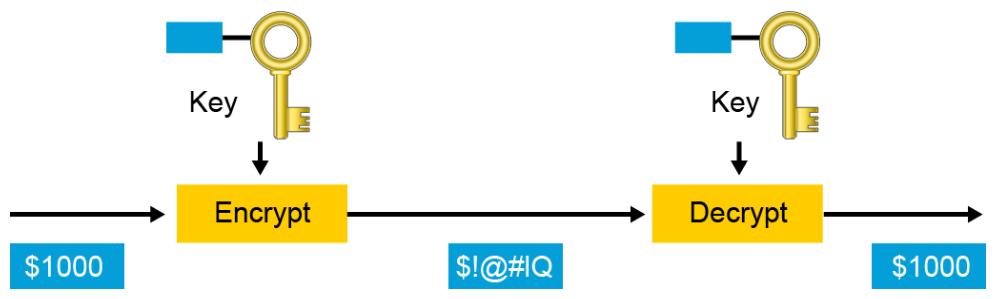

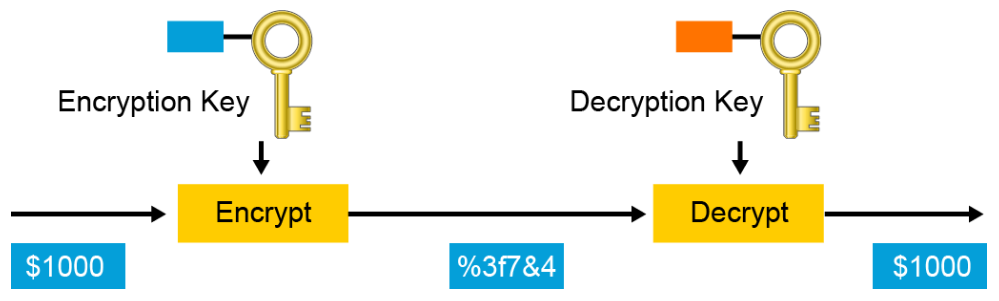

A key is a required parameter for encryption algorithms. There are two classes of encryption algorithms, which differ in their use of keys:

- Symmetric encryption algorithm: Uses the same key to encrypt and decrypt data

- Asymmetric encryption algorithm: Uses different keys to encrypt and decrypt data

Cryptanalysis

Cryptanalysis is the practice of breaking codes to obtain the meaning of encrypted data. An attacker who tries to break an algorithm or encrypted ciphertext may use one of the following attacks:

- Brute-force attack: In a brute-force attack, an attacker tries every possible key with the decryption algorithm, knowing that eventually one of the keys will work. All encryption algorithms are vulnerable to this attack. On average, a brute-force attack will succeed about 50 percent of the way through the key space, which is the set of all possible keys. The objective of modern cryptographers is to have a key space large enough that it takes too much money and too much time to accomplish a brute-force attack.

Note: Existing technology and computing power has resulted in cracking machines that are able to crack DES (Data Encryption Standard) in just a few hours. It is estimated that it would take 149 trillion years to crack AES (Advanced Encryption Standard) using the same method. - Ciphertext-only attack: In a ciphertext-only attack, the attacker has the ciphertext of several messages, all of which have been encrypted using the same encryption algorithm, but the attacker has no knowledge of the underlying plaintext. The job of the attacker is to recover the plaintext of as many messages as possible—or better yet, to deduce the key or keys that are used to encrypt the messages in order to decrypt other messages that are encrypted with the same keys. The attacker can use statistical analysis to achieve the result. These kinds of attacks are no longer practical, because modern algorithms produce pseudorandom output that is resistant to statistical analysis.

- Known-plaintext attack: In a known-plaintext attack, the attacker has access to the ciphertext of several messages but also knows something about the plaintext that underlies that ciphertext. With knowledge of the underlying protocol, file type, or some characteristic strings that may appear in the plaintext, the attacker uses a brute-force attack to try keys, until decryption with the correct key produces a meaningful result. This attack may be the most practical attack, because attackers can usually assume the type and some features of the underlying plaintext, if they can only capture the ciphertext. However, modern algorithms with enormous key spaces make it unlikely for this attack to succeed, because on average an attacker has to search through at least half of the key space to be successful.

- Chosen-plaintext attack: In a chosen-plaintext attack, the attacker chooses what data the encryption device encrypts and observes the ciphertext output. A chosen-plaintext attack is more powerful than a known-plaintext attack, because the attacker gets to choose the plaintext blocks to encrypt, allowing the attacker to choose plaintext that might yield more information about the key. This attack might not be very practical, because it is often difficult or impossible to capture both the ciphertext and plaintext, unless the trusted network has been broken into and the attacker already has access to confidential information.

- Chosen-ciphertext attack: In a chosen-ciphertext attack, the attacker can choose different ciphertext to be decrypted and has access to the decrypted plaintext. With the pair, the attacker can search through the key space and determine which key decrypts the chosen ciphertext in the captured plaintext. For example, the attacker has access to a tamper-proof encryption device with an embedded key. The attacker must deduce the embedded key by sending data through the box. This attack is analogous to the chosen-plaintext attack. This attack might not be very practical, because it is often difficult or impossible to capture both the ciphertext and plaintext, unless the trusted network has been broken into, and the attacker already has access to confidential information.

- Birthday attack: The birthday attack gets its name because of an amazing statistical probability that is involved in two individuals having the same birthday. According to statisticians, the probability that two people in a group of 23 people share the same birthday is greater than 50 percent.

This particular attack is a form of brute-force attack against hash functions. If a specific function, when supplied with a random input, returns one of k equally likely values, then by repeating the function with different inputs, the same output is expected after 1.2k^1/2 number of times.

Note: To test the birthday theory, input 365 in the place of k. - Meet-in-the-middle: The meet-in-the-middle attack is a known-plaintext attack. In a meet-in-the-middle attack, the attacker knows a portion of the plaintext and the corresponding ciphertext. The plaintext is encrypted with every possible key, and the results are stored. The ciphertext is then decrypted by using every key, until one of the results matches one of the stored values.

Symmetric Encryption Algorithms

Symmetric encryption algorithms use the same key for encryption and decryption. Therefore, the sender and the receiver must share the same secret key before communicating securely. The security of a symmetric algorithm rests in the secrecy of the shared key; by obtaining the key, anyone can encrypt and decrypt messages. Symmetric encryption is often called secret-key encryption. Symmetric encryption is the more traditional form of cryptography. The typical key-length range of symmetric encryption algorithms is 40 to 256 bits.

Because symmetric algorithms are usually quite fast, they are often used for wire-speed encryption in data networks. Symmetric algorithms are based on simple mathematical operations and can easily be accelerated by hardware. Because of their speed, you can use symmetric algorithms for bulk encryption when data privacy is required, such as to protect a VPN.

On the other hand, key management can be a challenge. The communicating parties must obtain a common secret key before any encryption can occur. Therefore, the security of any cryptographic system depends greatly on the security of the key management methods.

Because of their speed, symmetric algorithms are frequently used for encryption services, with additional key management algorithms providing secure key exchange.

Note:

Symmetric encryption algorithms are sometimes referred to as private-key encryption. Examples of symmetric encryption algorithms are DES, 3DES, AES, IDEA, RC2/4/5/6, and Blowfish.

Symmetric Encryption Key Lengths

Modern symmetric algorithms use key lengths that range from 40 to 256 bits. This range gives symmetric algorithms key spaces that range from 2^40 (1,099,511,627,776 possible keys) to 2^256 (1.5 x 1077) possible keys. Every additional bit in the key length doubles the number of possible key values. This large range is the difference between whether the algorithm is vulnerable to a brute-force attack or not. If you use a key length of 40 bits, then your encryption is likely to be broken relatively easily with a brute-force attack. In contrast, if your key length is 256 bits, it is not likely that a brute-force attack will be successful, because the key space is too large.

Key lengths greater than or equal to 80 bits can be trusted. Key lengths of less than 80 bits are considered obsolete, regardless of the strength of the algorithm.

Comparing Symmetric Encryption Algorithms

Symmetric encryption algorithms operate under the same framework, but they present considerable differences. Analyzing these algorithms requires comparing their key strength, complexity, and performance.

Here are some of the most widely used symmetric encryption algorithms:

- DES

- 3DES

- AES

- RC4

DES is a symmetric encryption algorithm that usually operates in block mode, in which it encrypts data in 64-bit blocks. The DES algorithm is essentially a sequence of permutations and substitutions of data bits combined with an encryption key. Because DES is based on very simple mathematical functions, it can easily be implemented and accelerated in hardware. DES has a fixed key length. The key is actually 64 bits long, but only 56 bits are used for encryption; the remaining 8 bits are used for parity. The least significant bit of each key byte is used to indicate odd parity.

DES uses two standardized block cipher modes:

- ECB: In ECB (Electronic Code Book) mode, it serially encrypts each 64-bit plaintext block using the same 56-bit key. If two identical plaintext blocks are encrypted using the same key, their ciphertext blocks are the same.

- CBC: In CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode, each 64-bit plaintext block is XORed bitwise with the previous ciphertext block and then is encrypted with the DES key. Because of this process, the encryption of each block depends on previous blocks. Encryption of the same 64-bit plaintext block can result in different ciphertext blocks.

With advances in computer processing power, the original 56-bit DES key became too vulnerable to brute force attacks. One way to increase the DES effective key length, without changing the well-analyzed algorithm itself, is to use the same algorithm with different keys several times in a row. The technique of applying DES three times in a row to a plaintext block is called 3DES. Brute-force attacks on 3DES are considered unfeasible today. Because the basic algorithm has been well tested in the field for more than 35 years, it is considered very trustworthy.

3DES uses a method that is called 3DES-Encrypt-Decrypt-Encrypt (3DES-EDE) to encrypt plaintext. 3DES-EDE includes the following steps:

- The message is encrypted using the first 56-bit key, which is known as K1.

- The data is decrypted using the second 56-bit key, which is known as K2.

- The data is encrypted again, now using the third 56-bit key, which is known as K3.

The 3DES-EDE procedure provides encryption with an effective key length of 168 bits. If the keys K1 and K3 are equal, as in some implementations, then a less secure encryption of 112 bits is achieved. To decrypt the message, the opposite of the 3DES-EDE method is used, using the keys in reverse order.

Note:

Under certain circumstances, such as those required for a meet-in-the-middle attack, encrypting multiple times with different keys may provide less strength than the sum of the key lengths.

For several years, it was recognized that DES would eventually reach the end of its usefulness. In 1997, the AES initiative was announced, and the public was invited to propose candidate encryption schemes, one of which could be chosen as the encryption standard to replace DES. The U.S. Secretary of Commerce approved the adoption of AES as an official U.S. government standard, effective May 26, 2002.

AES is an iterated block cipher, which means that the initial input block and cipher key undergo multiple transformation cycles before producing output. It is based on the more general Rijndael cipher. Rijndael specifies variable block sizes and key sizes, but AES specifically uses keys with a length of 128, 192, or 256 bits to encrypt 128-bit blocks.

AES was chosen to replace DES and 3DES, because the key length of AES is much stronger than DES, and AES runs faster than 3DES on comparable hardware. AES is more efficient than DES and 3DES on comparable hardware, usually by a factor of five when it is compared with DES. Also, AES is more suitable for high-throughput, low-latency environments, especially if pure software encryption is used.

Ron Rivest has authored several encryption algorithms that are designated with an RC followed by an integer. Of them, RC4 is the most prevalent today. It is a stream cipher. It can be deployed in many ways, but is most well-known for its use to secure web traffic in SSL and TLS. The algorithm is a variable key-size Vernam stream cipher. It is not considered a one-time pad, because its key is not random. The cipher can be expected to run very quickly in software. It is considered secure, although it can be implemented insecurely, as in WEP, and new research has begun to expose some weakness in RC4.

Note:

Many other symmetric algorithms are available, including SEAL, IDEA, Blowfish, Twofish, and Serpent.

Asymmetric Encryption Algorithms

Asymmetric algorithms utilize a pair of keys for encryption and decryption. The paired keys are intimately related and are generated together. Most commonly, an entity with a key pair will share one of the keys (the public key) and it will keep the other key in complete secrecy (the private key). The private key cannot, in any reasonable amount of time, be calculated from the public key. Data that is encrypted with the private key requires the public key to decrypt. Conversely, data that is encrypted with the public key requires the private key to decrypt. Asymmetric encryption is also known as public key encryption.

The typical key length range for asymmetric algorithms is 512 to 4096 bits. You cannot directly compare the key length of asymmetric and symmetric algorithms, because the underlying design of the two algorithm families differs greatly.

Examples of asymmetric cryptographic algorithms include RSA, DSA, ElGamal, and elliptic curve algorithms.

RSA is one of the most common asymmetric algorithms. Ron Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Len Adleman invented the RSA algorithm in 1977. It was a patented public-key algorithm. The patent expired in September 2000, so the algorithm is now in the public domain. Of all the public-key algorithms that have been proposed over the years, RSA is by far the easiest to understand and implement.

The RSA algorithm is very flexible, because it has a variable key length that allows speed to be traded for the security of the algorithm, if necessary. Current RSA keys are usually 1024 to 4096 bits long. Smaller keys require less computational overhead to use, large keys provide stronger security. Some systems have system-dependent maximum key sizes, so care must be taken when selecting key sizes to maintain compatibility.

RSA has withstood years of extensive cryptanalysis, and although the security of RSA has been neither proved nor disproved, its longevity does suggest a confidence level in the algorithm. The security of RSA is based on the difficulty of factoring very large numbers, which means breaking large numbers into multiplicative factors. If an easy method of factoring these large numbers was discovered, the effectiveness of RSA would be destroyed.

The RSA algorithm is based on the fact that each entity has two keys, a public key and a private key. The public key can be published and given away, but the private key must be kept secret. It is not possible to determine, using any computationally feasible algorithm, the private key from the public key, and vice versa. What one of the keys encrypts, the other key decrypts, and vice versa.

RSA keys are long term and are usually changed or renewed after a few months.

Asymmetric algorithms are substantially slower than symmetric algorithms. Their design is based on computational problems, such as factoring extremely large numbers or computing discrete logarithms of extremely large numbers. Because they lack speed, asymmetric algorithms are typically used in low-volume cryptographic mechanisms, such as digital signatures and key exchange. However, the key management of asymmetric algorithms tends to be simpler than symmetric algorithms, because usually one of the two encryption or decryption keys can be made public.

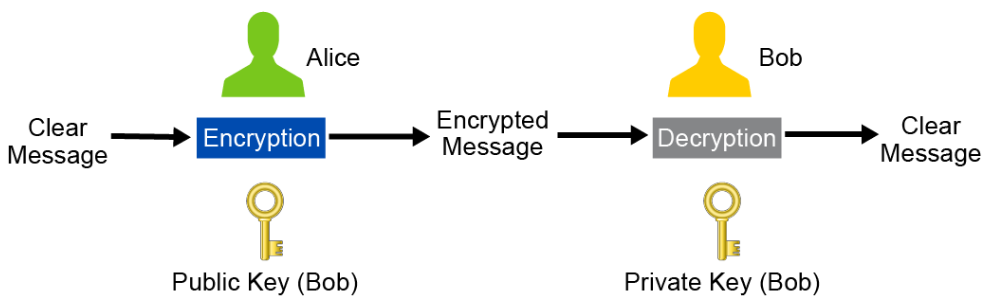

The security services that are provided by asymmetric encryption can vary by scenario. Imagine that Bob has generated a public/private key pair. Bob keeps the private key totally secret but publishes the public key so it is available to everyone. Alice has a message that she wants to send to Bob in private. If Alice encrypts the message using Bob’s public key, only Bob has the private key that is required to decrypt the message, providing confidentiality. This scenario is depicted in the figure below.

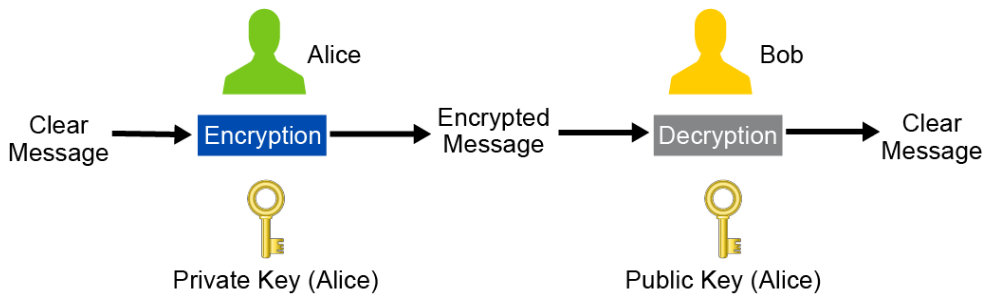

Now, imagine that Alice has an important message that she wants to send to Bob. Alice encrypts the message with her private key and sends it to Bob. Bob can use Alice’s public key to decrypt the message, but so can anyone else who has intercepted the message, which does not provide privacy, but there is a security benefit. If Bob can use Alice’s public key to decrypt the message, Bob then knows that the message was originally encrypted with Alice’s private key. Only Alice has that private key, so Bob knows that the message originates from Alice, which provides origin authentication. This scenario is depicted in the figure below.

PGP (Pretty Good Privacy) provides a common encryption methodology for email. It requires both parties to generate public/private key pairs and to share their public keys with each other. The content of emails is encrypted twice, once with the sender’s private key, and again with the receiver’s public key. The receiver must reverse the process, decrypting the message with their private key and then decrypting again with the sender’s public key. This methodology provides both privacy and origin authentication. Understand, asymmetric encryption is computationally expensive. The scenario works well for email which does not require real-time transmission speeds. Protocols which do bulk data encryption in real time, such as SSH, SSL, and IPsec, will use symmetric encryption for the bulk data encryption. They often, however, use asymmetric algorithms in their key management procedures.

Diffie-Hellman Key Agreement

The DH key agreement method allows two parties to share information over an untrusted network and mutually compute an identical shared secret that cannot be computed by eavesdroppers who intercept the shared information. The mathematical operations are relatively easy to describe, expensive to compute, and intractable to reverse.

The DH key agreement method can be used in protocols such as SSL/TLS, SSH, and IKE.

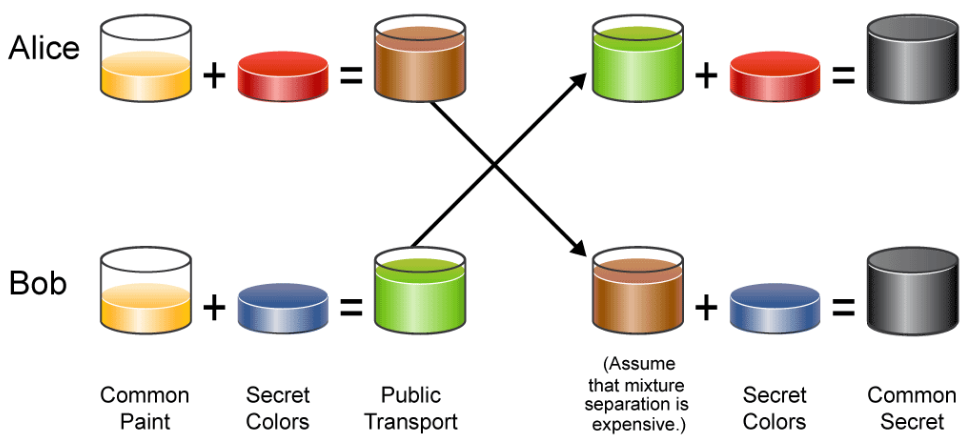

The figure simplifies the concept of the DH key agreement process by using colors instead of using math with very large numbers:

- The DH key exchange begins with two parties: Alice and Bob in the example.

- Alice and Bob agree on an arbitrary common color that does not need to be kept secret, which represents a large prime number p and a generator g that both parties agreed on.

- Each of them then selects a secret color that they keep secret to themselves. The secret color is never exchanged to the other party, which represents the chosen secret private key of each party.

- The crucial part of the process is that Alice and Bob now mix their secret color together with the shared common color, then publicly exchange their mixed colors to each other, which represents the public key that each party sends to the other party. Each party's public key is calculated using the generator g, the prime number p, and their own chosen secret private key.

- Finally, Bob and Alice each mix together the color they received from the partner with their own private color. The result is a final color mixture that is identical to the partner's final color mixture, which represents the resulting shared secret key between Bob and Alice. Each party calculates the shared secret using the other party's public key, each party's own chosen secret key, and the prime number p.

- If a third party (Eve, for example) had been listening in on the exchange, it would be computationally difficult for Eve to determine the final color mixture.

The mathematical model in the DH key exchange process:

- p = large prime number, can be known to Alice, Bob, and Eve.

- g = based or generator, can be known to Alice, Bob, and Eve.

- a = Alice's chosen private key, which is known only to Alice.

- b = Bob's chosen private key, which is known only to Bob.

- A = Alice's calculated public key using g, p, and a, can be known to Alice, Bob, and Eve. A = g^a mod p.

- B = Bob's calculated public key using g, p, and b, can be known to Alice, Bob, and Eve. B = g^b mod p.

- s = The shared secret key, which is calculated by using the other party's public key, each party's own chosen secret key, and the prime number p, is known to both Alice and Bob, but not to Eve.

- s = B^a mod p (calculated by Alice).

- s = A^b mod p (calculated by Bob).

- s can also be calculated using the formula s = g^ab mod p which requires knowledge of both parties chosen private key.

- After each party calculates the shared secret key s independently, each party will end up with the exact same value s. All three formulas for s will produce the same result. s = g^ab mod p = B^a mod p = A^b mod p.

Diffie-Hellman used different DH groups to determine the strength of the key that is used in the key agreement process. The higher group numbers are more secure, but require additional time to compute the key. Each DH group specifies the values of p and g. DH groups are supported by Cisco IOS Software and the associated size of the value of the prime p:

- DH Group 1: 768 bits

- DH Group 2: 1024 bits

- DH Group 5: 1536 bits

- DH Group 14: 2048 bits

- DH Group 15: 3072 bits

- DH Group 16: 4096 bits

- A DH key agreement can also be based on elliptic curve cryptography. Its use is included in the Suite B cryptographic suites. DH groups 19, 20, and 24, based on elliptic curve cryptography, are also supported by Cisco IOS Software.

Note:

The DH key exchanges always use the same DH private key. Each time the same two parties perform a DH key exchange, they will end up with the same shared secret. With ephemeral Diffie-Hellman, a temporary private key is generated for every DH key exchange, and thus the same private key is never used twice. This enables PFS (Perfect Forward Secrecy), which means that if the private key is ever exposed, any past communications are still secured.

Use Case: SSH

The connection process of SSHv1 provides a use case to help solidify your understanding of both symmetric and asymmetric encryption. SSH is a remote console protocol, like Telnet. But unlike Telnet, SSH is designed to provide privacy, data integrity, and origin authentication. SSHv1 should be considered legacy, as SSHv2 was designed to overcome some security shortcomings in SSHv1. However, the key exchange methodology that is used by SSHv2 is more complex, using DH (Diffie-Hellman).

SSHv1 makes clever use of asymmetric encryption to facilitate symmetric key exchange. Computationally expensive asymmetric encryption is only required for a small step in the negotiation process. After key exchange, much more computationally efficient symmetric encryption is used for bulk data encryption between the client and server.

SSHv1 uses a connection process as follows:

- The client connects to the server and the server presents the client with its public key.

- The client and server negotiate the security transforms. The two sides agree to a mutually supported symmetric encryption algorithm. This negotiation occurs in the clear. A party that intercepts the communication will be aware of the encryption algorithm that is agreed upon.

- The client constructs a session key of the appropriate length to support the agreed-upon encryption algorithm. The client encrypts the session key with the server’s public key. Only the server has the appropriate private key that can decrypt the session key.

- The client sends the encrypted session key to the server. The server decrypts the session key using its private key. At this point, both the client and the server have the shared session key. That key is not available to any other systems. From this point on, the session between the client and server is encrypted using a symmetric encryption algorithm.

- With privacy in place, user authentication ensues. The user’s credentials and all other data are protected.

Not only does the use of asymmetric encryption facilitate symmetric key exchange, it also facilitates peer authentication. If the client is aware of the server’s public key, it would recognize if it connected to a nonauthentic system when the nonauthentic system provided a different public key. Understand that the nonauthentic system cannot provide the real server’s public key because it does not have the corresponding private key. While the ability to provide peer authentication is certainly a step in the right direction, the responsibility is generally on the user to have prior knowledge of the server’s public key. Generally, when the SSH client software connects to a new server for the first time, it will display the server’s public key (or a hash of the server’s public key) to the user. The client software will only continue if the user authorizes the server’s public key. But few users will take steps to verify that the public key is indeed authentic, which presents a challenge.

Digital Signatures

Suppose that a customer sends transaction instructions via an email to a stockbroker, and the transaction turns out badly for the customer. It is conceivable that the customer could claim never to have sent the transaction order or that someone forged the email. The brokerage could protect itself by requiring the use of digital signatures before accepting instructions via email.

Handwritten signatures have long been used as a proof of authorship of, or at least agreement with, the contents of a document. Digital signatures can provide the same functionality as handwritten signatures, and much more.

The idea of encrypting a file with your private key is a step toward digital signatures. Anyone who decrypts the file with your public key knows that you were the one who encrypted it. But, since asymmetric encryption is computationally expensive, it is not optimal. Digital signatures leave the original data unencrypted. It does not require expensive decryption to simply read the signed documents. In contrast, digital signatures use a hash algorithm to produce a much smaller fingerprint of the original data. This fingerprint is then encrypted with the signer’s private key. The document and the signature are delivered together. The digital signature is validated by taking the document and running it through the hash algorithm to produce its fingerprint. The signature is then decrypted with the sender’s public key. If the decrypted signature and the computed hash match, then the document is identical to what was originally signed by the signer.

Usually asymmetric algorithms, such as RSA and DSA, are used for digital signatures.

RSA Digital Signatures

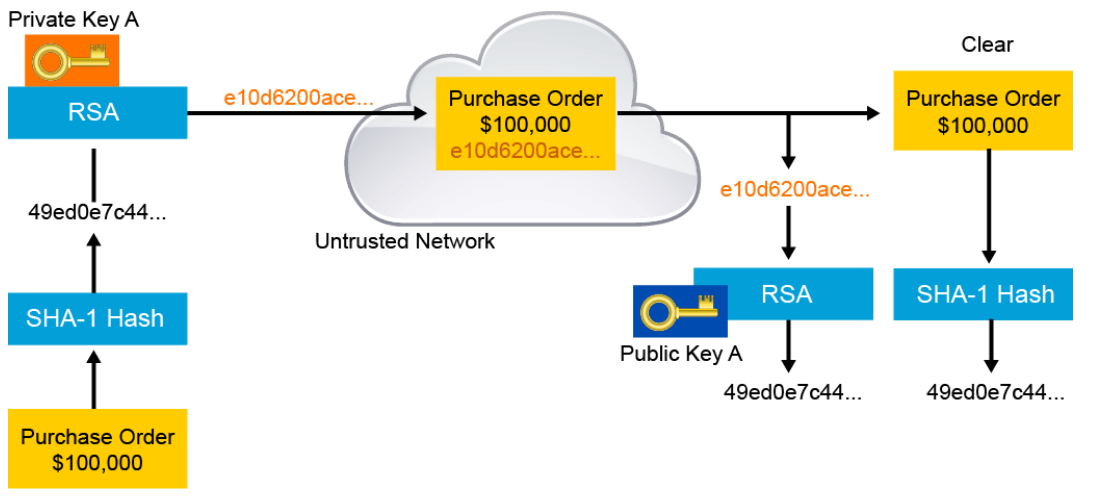

The current signing procedures of digital signatures are not simply implemented by public key operations. In fact, a modern digital signature is based on a hash function and a public key algorithm, as illustrated below.

The signature process is as follows:

- The signer makes a hash, or fingerprint, of the document, which uniquely identifies the document and all its contents.

- The signer encrypts the hash with only the private key of the signer.

- The encrypted hash, which is known as the signature, is appended to the document.

The verification process is as follows:

- The verifier obtains the public key of the signer.

- The verifier decrypts the signature using the public key of the signer. This step unveils the assumed hash value of the signer.

- The verifier makes a hash of the received document, without its signature, and compares this hash to the decrypted signature hash. If the hashes match, the document is authentic. The match means that the document has been signed by the assumed signer and has not changed since it was signed.

The example illustrates how the authenticity and integrity of the message is ensured, even though the actual text is public. Both encryption and digital signatures are required to ensure that the message is private and has not changed.

Note:

The RSA algorithm is currently the most common method for signature generation, and is used widely in that role by e-commerce systems and interactive purchasing systems.

Digital signatures provide three basic security services in secure communications:

- Authenticity of digitally signed data: Digital signatures authenticate a source, proving that a certain party has seen and has signed the data in question.

- Integrity of digitally signed data: Digital signatures guarantee that the data has not changed from the time it was signed.

- Nonrepudiation of the transaction: The recipient can take the data to a third party, and the third party accepts the digital signature as a proof that this data exchange did take place. The signing party cannot repudiate that it has signed the data.

To achieve these goals, digital signatures have the following properties:

- The signature is authentic: The signature convinces the recipient of the document that the signer signed the document.

- The signature is not forgeable: The signature is proof that the signer, and no one else, signed the document.

- The signature is not reusable: The signature is a part of the document and cannot be moved to a different document.

- The signature is unalterable: After a document is signed, it cannot be altered.

- The signature cannot be repudiated: Signers cannot claim later that they did not sign it.

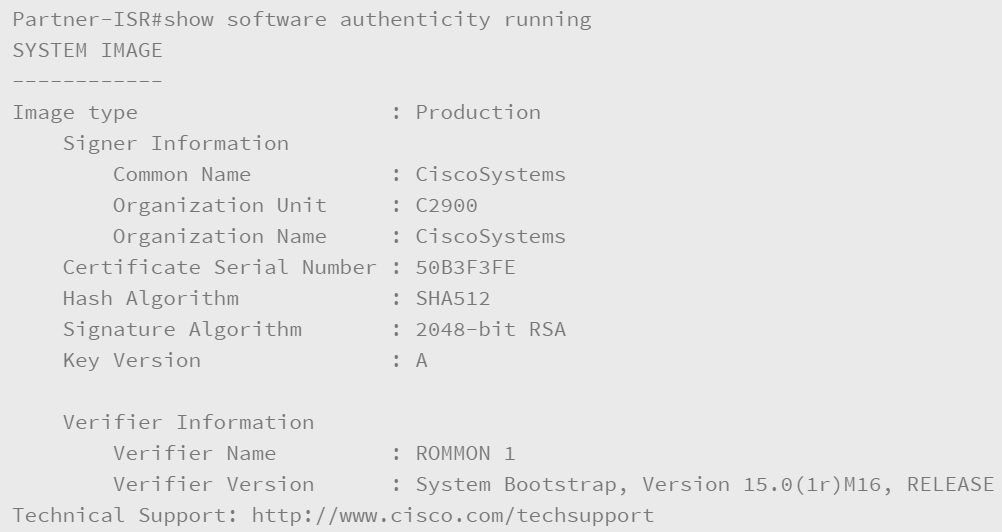

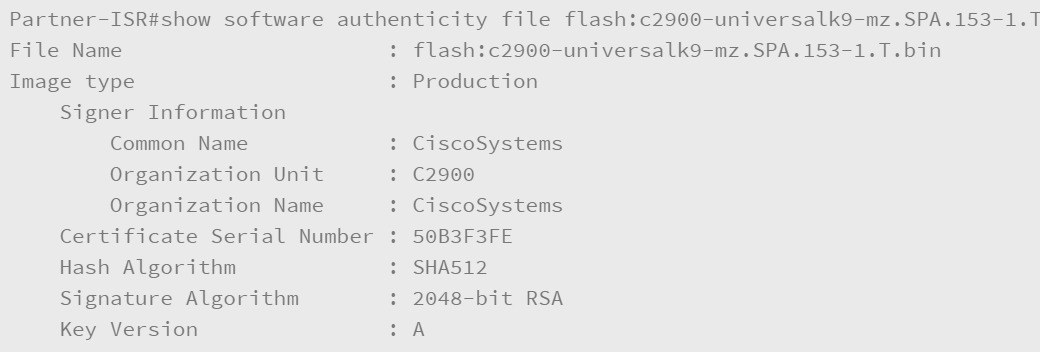

Practical Example: Digitally Signed Cisco Software

The Digitally Signed Cisco Software feature (added in Cisco IOS Software Release 15.0(1)M for the Cisco 1900, 2900, and 3900 Series routers) facilitates the use of Cisco IOS Software that is digitally signed, with the use of secure asymmetrical (public key) cryptography.

Digitally signed Cisco IOS Software is identified by a three-character extension in the image name. The Cisco software build process creates a Cisco IOS image file that contains a file extension that is based on the signing key that was used to sign images. These file extensions are:

- SPA

- SSA

The first S indicates that the software is digitally signed. The second character specifies a production (P) or special (S) image. The third character indicates the key version that was used to sign the image. Currently, key version A is used. When a key is replaced, the key version will be incremented alphabetically to B, C, and so on.

A digitally signed image carries an encrypted (with a private key) hash of itself. Upon check, the device decrypts the hash with the corresponding public key from the keys it has in its key store and also calculates its own hash of the image. If the decrypted hash matches the calculated image hash, the image has not been tampered with and can be trusted.

Digitally signed Cisco software keys are identified by the type and version of the key. A key can be a special, production, or rollover key type. Production and special key types have an associated key version that increments alphabetically whenever the key is revoked and replaced. ROMMON and regular Cisco IOS images are both signed with a special or production key when you use the Digitally Signed Cisco Software feature. The ROMMON image is upgradable and must be signed with the same key as the special or production image that is loaded.

The first command that is shown below is used by the router administrator to verify the integrity of the running IOS image. The second command is used to verify the integrity of the c2900-universalk9-mz.SPA.153-1.T.bin image that is stored in the flash memory.

PKI (Public Key Infrastructure) Overview

A substantial challenge with both asymmetric encryption and digital certificates is the secure distribution of public keys. How do you know that you have the real public key of the other system and not the public key of an attacker who is trying to deceive you? In this scenario, the public key infrastructure comes to play. Entities enroll with a PKI and receive identity certificates that are signed by a certificate authority. Among the identity information included in the certificate is the entity’s public key. The certificate authority’s digital signature on the identity certificate validates that the included public key is the real public key belonging to the associated entity. A system will only accept the signed digital certificate if it trusts the CA (Certification Authority). The CA plays the role of a trusted third party.

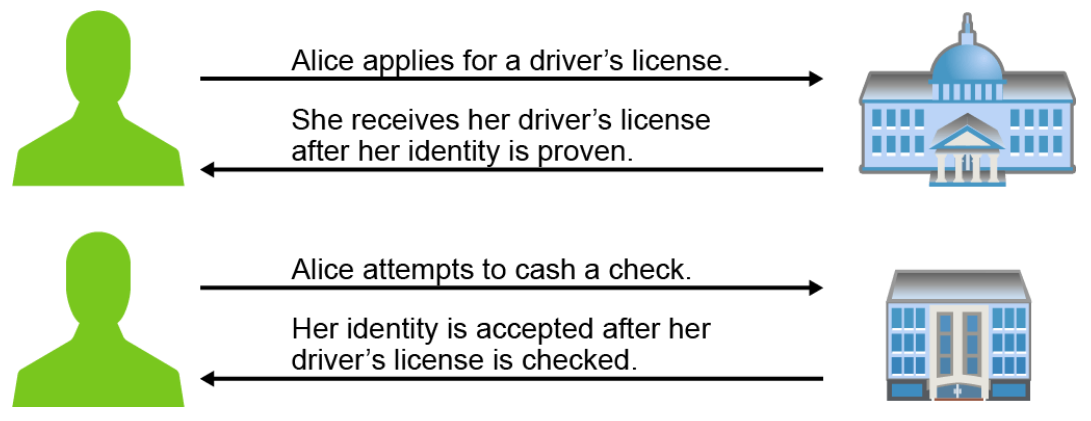

Trusted Third-Party Example

In the figure below, Alice applies for a driver’s license. As part of this process, Alice submits evidence of identity and qualifications to drive. Once the application is approved, a license is issued.

Later, Alice needs to cash a check at the bank. Upon presenting the check to the bank teller, the bank teller asks for ID. The bank, because it trusts the government agency that issued the driver’s license, verifies the identity with the license and cashes the check.

Note:

Certificate authorities function like the driver’s license bureau in this example. The driver’s license is analogous to a certificate in a PKI or a technology that supports certificates.

PKI Terminology and Components

A PKI is the service framework that is used to support large-scale public key-based technologies. It provides the base for security services such as encryption, authentication, and nonrepudiation. A PKI allows for very scalable solutions which require the management of systems identities, user identities, or both, and is an important authentication solution for VPNs. A PKI uses specific terminology to name its components.

Two very important terms must be defined when talking about a PKI:

- CA (Certification Authority): The trusted third party that signs the public keys of entities in a PKI-based system.

- Certificate: A document, which in essence binds together the name of the entity and its public key, which has been signed by the CA.

Many vendors offer CA servers as a managed service or as an end-user product: VeriSign, Entrust Technologies, and GoDaddy are some examples. Organizations may also implement private PKIs using Microsoft Server or Open SSL.

PKI has been standardized to allow interoperability across a wide variety of applications and vendors. In the early 1990s, RSA Security Inc. devised and published a set of standards that are known as PKCS (Public-Key Cryptography Standard). While not true industry standards, as they were specified and maintained by a single organization, several of the standards have been accepted into the standards track processes of recognized standards organizations.

Some of the PKCSs include:

- PKCS #1: RSA Cryptography Standard

- PKCS #3: D-H Key Agreement Standard

- PKCS #5: Password-Based Cryptography Standard

- PKCS #6: Extended-Certificate Syntax Standard

- PKCS #7: Cryptographic Message Syntax Standard

- PKCS #8: Private-Key Information Syntax Standard

- PKCS #10: Certification Request Syntax Standard

- PKCS #12: Personal Information Exchange Syntax Standard

- PKCS #13: Elliptic Curve Cryptography Standard

- PKCS #15: Cryptographic Token Information Format Standard

X.509 is an ITU-T standard for PKI which specifies, among other things, the formats for identity certificates and certificate validation algorithms. The IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force) formed the PKIX working group to support standards development of X.509.

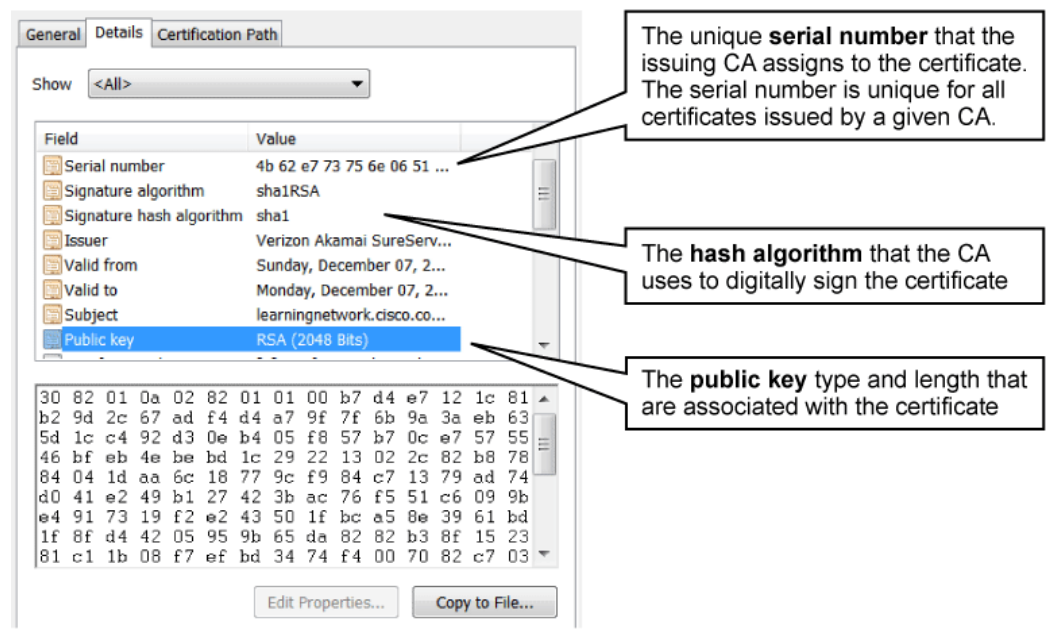

Currently, digital identity certificates use the X.509 version 3 structure:

- Version

- Serial number

- Algorithm ID

- Issuer

- Validity

- Not before

- Not after - Subject

- Subject public key info

- Public key algorithm

- Subject public key - Issuer unique identifier (optional)

- Subject unique identifier (optional)

- Extensions (optional)

- Certificate signature algorithm

- Certificate signature

As you can see, digital identity certificates contain a set of identity information about an entity, including that entity’s public key. The last element in the certificate is a signature. The CA signs the certificate. It takes all the certificate data and runs it through the specified hash algorithm to compute a fingerprint of the certificate data. It then encrypts the hash using its private key. The encrypted hash is the signature and it is appended to the certificate. Any system can then validate a certificate using the CA’s public key. The system takes the certificate data and runs it through the specified hash algorithm to produce a fingerprint of the certificate which it received. It then decrypts the certificate signature using the CA’s public key. If the computed hash and the decrypted signature match, then the signature is valid.

PKI Operations

A PKI facilitates highly scalable trust relationships. PKIs can be further scaled using a hierarchy of CAs with a root CA signing the identity certificates of subordinate CAs. For simplicity, this discussion will present a single CA PKI.

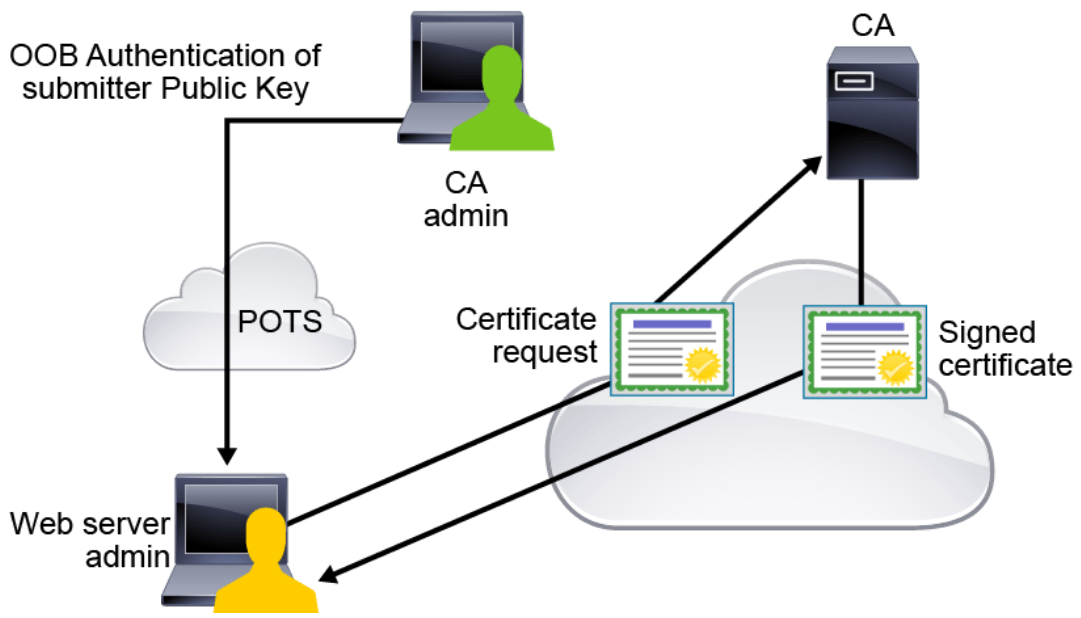

The PKI is an example of a trusted third-party system. The basis of the trust is the CA’s public key. All systems that leverage the PKI must have the CA’s public key, from the CA’s own identity certificate. The CA’s own identity certificate is unique as it is self-signed. For many systems, the distribution of CA certificates is handled automatically. For example, commercial web browsers come with a set of public CA root certificates pre-installed, and organizations push their private CA root certificate to clients through various software distribution methods. But in some instances, particularly when a system needs to enroll with a PKI to obtain an identity certificate for itself, the CA certificate must be requested and installed manually. Then, it is advisable to use an out-of-band method to validate the certificate. For example, the CA administrator can be contacted via the phone to obtain the fingerprint of the valid CA identity certificate. The goal is to verify that the CA certificate that was received was the authentic CA certificate containing the authentic CA public key and not a certificate that is provided by an attacker containing the attacker’s public key.

Certificate Enrollment

To obtain an identity certificate, a system administrator will enroll with the PKI. The first step is to obtain the CA’s identity certificate. The next step is to create a CSR (Certificate Signing Request (PKCS #10)). The CSR contains the identity information that is associated with the enrolling system, which can include data such as the system name, the organization to which the system belongs, and location information. Most importantly, the enrolling system’s public key is included with the CSR. Depending on the circumstance, the CA administrator may need to contact the enroller and verify the data before the request can be approved. If the request is approved, the CA will take the identity data from the CSR, and add in the CA-specified data, such as the certificate serial number, the validity dates, and the signature algorithm, to complete the X.509v3 certificate structure. It will then sign the certificate by hashing the certificate data and encrypting the hash with its private key. The signed certificate is then made available to the enrolling system.

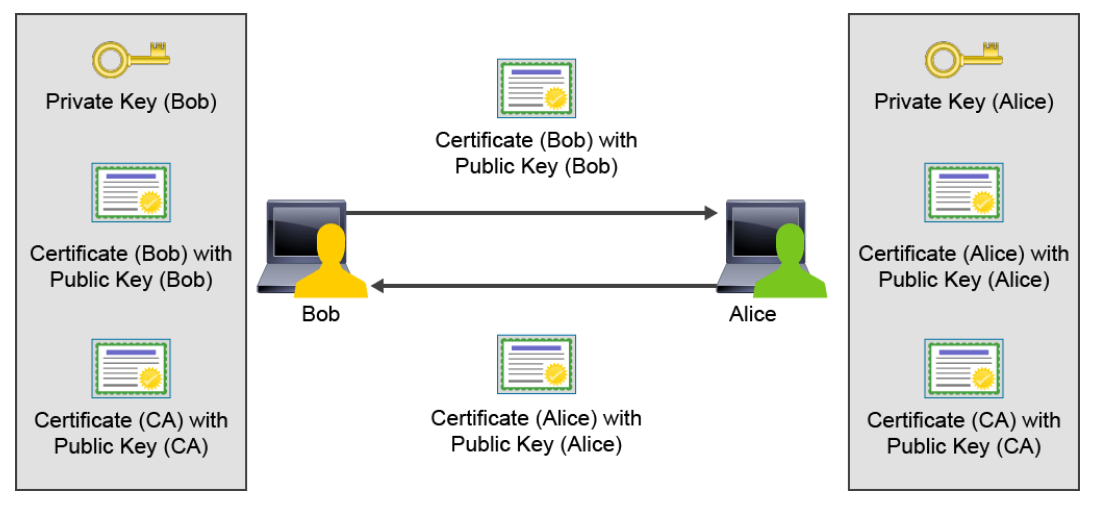

Authentication Using Certificates

It is important to understand that the CA is not involved in the certificate validation process. Systems that need to validate the identity certificate of other systems will have the root CA certificate. They will use the CA’s public key to validate the signature on any certificate they receive. It is also important to understand that the certificate does not so much identify the entity of the peer. It only identifies the valid public key of the peer. To be sure that the peer is actually the entity that is identified in the certificate, a system must challenge the peer to prove that it has the private key that is associated with the validated public key. For example, a message can be encrypted with the validated public key and sent to the peer. If the peer can successfully decrypt the message, then the peer must have the associated private key and is therefore the system that is identified by the digital certificate.

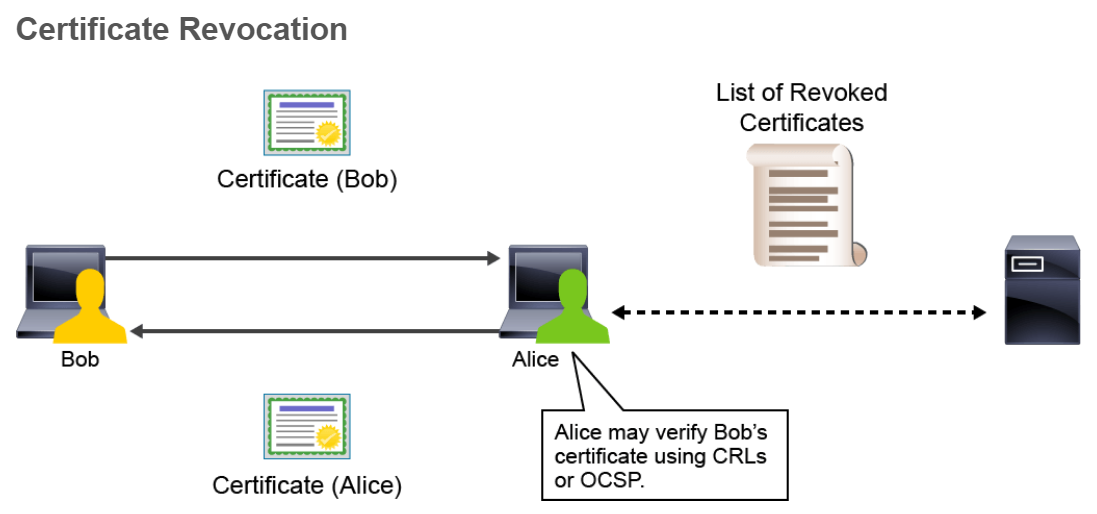

Digital certificates can be revoked if keys are thought to be compromised, or if the business use of the certificate calls for revocation (for example, VPN access privileges have been terminated). If keys are thought to be compromised, generating new keys forces the creation of a new digital certificate, rendering the old certificate invalid and a candidate for revocation. On the other hand, a consultant might obtain a digital certificate for VPN access into the corporate network only during the contract.

Certificate revocation is also a centralized function, providing “push” and “pull” methods to obtain a list of revoked certificates—frequently or on-demand—from a centralized entity. In some instances, the CA server acts as the issuer of certificate revocation information.

Certificate Revocation Check Methods

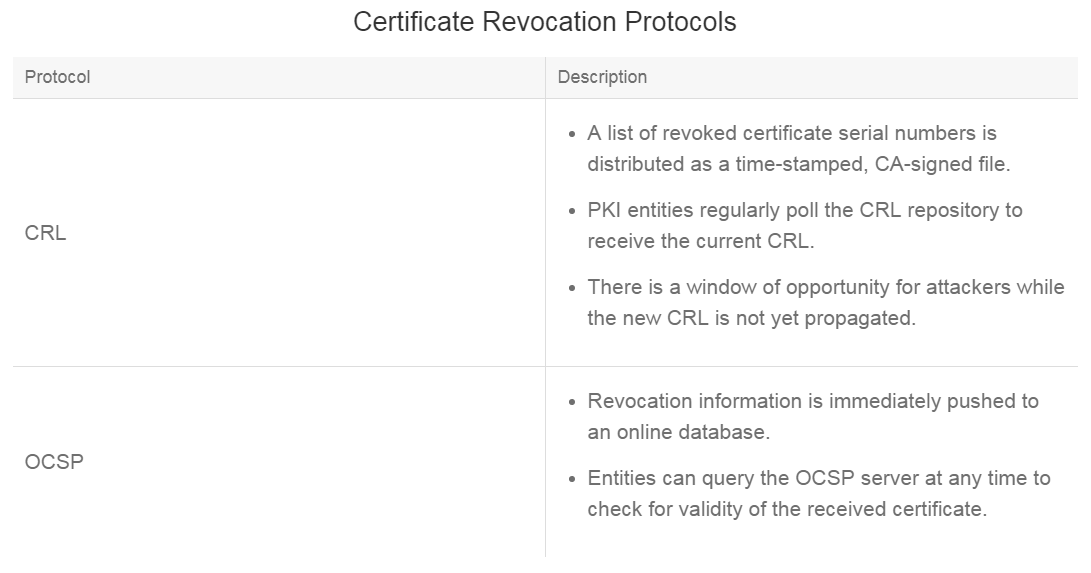

Several methods can be used to check for certificate revocation. Currently, the most prevalent methods are CRLs (Certificate Revocation List) and OCSP (Online Certificate Status Protocol). The table lists benefits and limitations of each protocol:

Use Case: SSL/TLS

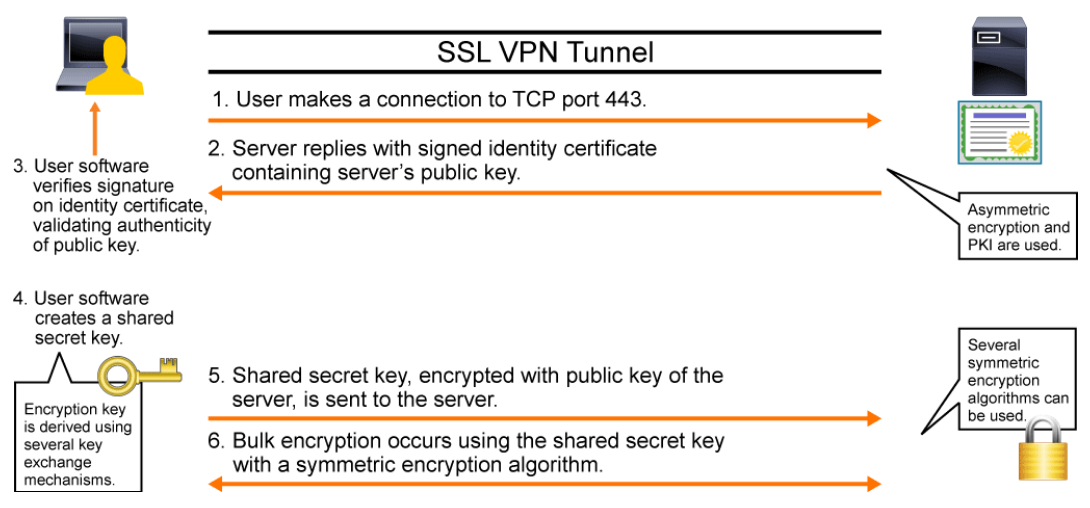

SSL (Secure Socket Layer)/TLS (Transport Layer Security) is the most widely visible use of certificate-based peer authentication. SSL was developed by Netscape in the 1990s to provide secure transactions between web browsers and web servers in support of commerce over the Internet. SSL became a de facto standard, but it has since been made obsolete by TLS which is standardized by the IETF. TLS version 1.0 was defined in RFC 2246 in 1999 and provided a standards-based upgrade to SSL version 3.0. TLS continues to evolve with TLS 1.3 in draft as of February 2015. Modern systems implement TLS, but the term SSL is often used interchangeably by IT professionals.

TLS uses PKI to authenticate peer systems and public key cryptography to facilitate the exchange of session keys that are used to encrypt the SSL session. Many applications use TLS to provide authentication and encryption. The most widely used application is HTTPS. Other well-known applications that were using poor authentication and no encryption were modified to be transported within TLS. Examples include SMTP, LDAP, and POP3.

The figure below depicts the steps that are taken in the negotiation of a new TLS connection between a web browser and a web server. SSL and TLS support a combination of cryptographic algorithms to provide the same services at various levels of risk. The figure illustrates the cryptographic architecture of SSL and TLS, based on the negotiation process of the protocol.

SSL and TLS are open enough to allow multiple cipher suites, and they are flexible enough to support more in the future, provided they adhere to protocol specifications. The structure and use of the cipher suite concept are defined in the documents that define the protocol (RFC 5246 for TLS version 1.2). This RFC defines mandatory cipher suites that must be implemented by all TLS-compliant applications. The only mandatory cipher suite is TLS_RSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA, including RSA for authentication and key exchange, AES for confidentiality (encryption), and SHA for integrity (Hashed Message Authentication Code).

In order to scale and support future protocols, TLS 1.2 defines a Cipher Suite Registry in RFC 2434, maintained by the IANA.

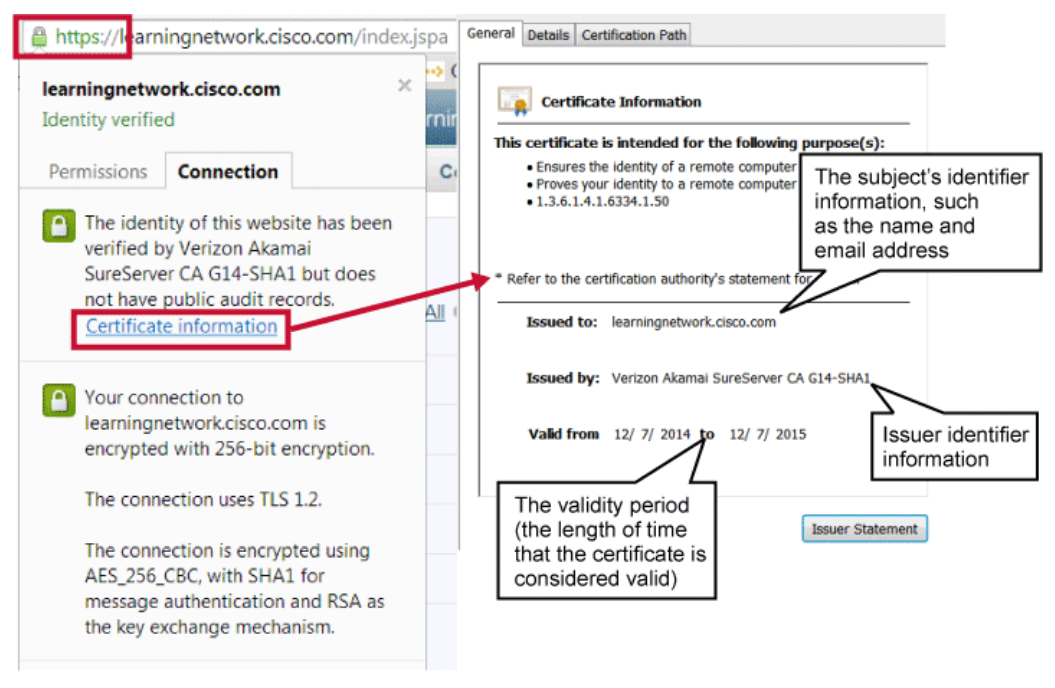

SSL/TLS Certificate Example

Web browsers, using a built-in store of root CA certificates, hide the details of validating TLS sessions from the user, unless there is an issue with the validation process. But even with successful validation, users can drill down into the details of the connection. Here are the certificate details that can be examined within a web browser.

- When the connection to the server is first initialized, the server provides its PKI certificate to the client, which contains the public key of the server and is signed with the private key of the CA that the owner of the server has used.

- To verify that the PKI certificate can be trusted, the signature of the CA that is in the certificate is checked. If the signature can be traced back to a public key that already is known to the client, the connection is considered to be trusted.

- Now that the connection is trusted, the client can send encrypted packets to the server. To encrypt the data traffic, the public key of the server is used.

- As public/private-key encryption is one-way encryption, only the server is capable of decrypting the traffic, by using its private key.

Using the Certification Path tab, you can view the path from the selected certificate to the CAs that issue the certificate. In order for the recipient of a certificate to trust the certificate, the recipient must verify that the certificate comes from a trusted source. This verification process is called path validation. Path validation involves processing public key certificates and their issuer certificates in a hierarchical fashion until the certification path terminates at a trusted, self-signed certificate, which is typically a root CA certificate. If there is a problem with one of the certificates in the path, or if the recipient cannot find a certificate, the certification path is considered a nontrusted certification path. A typical certification path includes a root certificate and one or more intermediate certificates. By clicking View Certificate, you can also learn more about the certificates for each CA in the path.

Web Browser Security Warnings

If there are any issues that are associated with validating the certificate of a web server, web browsers will display a security warning to the user. Unfortunately, many users will ignore the security warnings and blindly proceed with the connection under potentially hazardous conditions. The three most common issues that are associated with security warnings are as follows:

- Hostname/identity mismatch: URLs specify a web server name. If the name specified in the URL does not match the name that is specified in the server’s identity certificate, the browser will display a security warning. Hence, DNS is critical to support the use of PKI in web browsing, which may be benign under certain circumstances: for example, if the user knows the IP address of the server and specifies the IP address instead of the hostname. But attackers may register domain names that look very similar to authentic domain names. The browser will detect the mismatch, but the user may look at the certificate and think that it is acceptable.

- Validity date range: X.509v3 certificates specify two dates, not before and not after. If the current date is within those two values, there will be no warning. If it is outside the range, the web browser displays a message. The validity date range specifies the amount of time that the PKI will provide certificate revocation information for the certificate. When certificates expire, it facilitates the periodic changing of public/private key pairs on web servers. Expired certificates may simply be the result of administrator oversight, but they may also reflect more serious conditions.

- Signature validation error: If the browser cannot validate the signature on the certificate, there is no assurance that the public key in the certificate is authentic. Signature validation will fail if the root certificate of the CA hierarchy is not available in the browser’s certificate store. A common reason may be that the server uses a self-signed certificate. Many systems allow the creation of self-signed certificates to avoid the complexity or expense of joining a PKI. The use of self-signed certificates, however, puts the responsibility of certificate verification on the user, which is not optimal from a security perspective. Another possible cause of a signature verification error is that the certificate has been tampered with—for example, if an attacker has replaced the server’s real public key with the attacker’s public key.

Cipher Suite

As computational horsepower increases and cryptanalysis reveal weakness in the current crypto algorithms, the current crypto algorithms will constantly evolve and new crypto algorithms will be developed to improve security.

For example, DES, the data encryption standard which was approved by the U.S. National Bureau of Standards (NBS) in 1977, is now considered insecure. The NIST, successor to the NBS, officially withdrew DES as an approved option for federal government encryption in 2005. Whereas decrypting DES encrypted data in 1977 was cost-prohibitive, hardware and software to crack DES encryption efficiently is now available at a very reasonable price. Instead of the weaker DES, the AES was adopted by the NIST in 2001.

The SSL/TLS protocols were extensible and modular, allowing the server/client encryption, key exchange, and message authentication code algorithms to be changed without replacing the entire SSL/TLS protocol. For example, TLS version 1.2 added support for authenticated encryption modes, and support for the SHA-256 and SHA-384 hash algorithms, which are not supported in prior versions of TLS.

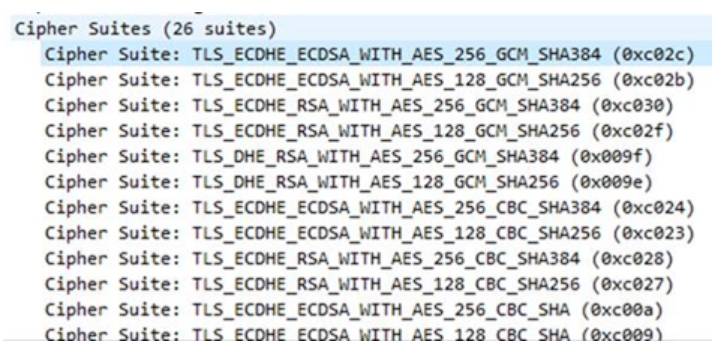

An SSL/TLS cipher suite is used to define a set of cryptographic algorithms including the authentication and key exchange algorithms (such as RSA), encryption algorithm (such as AES), message authentication code algorithm (such as SHA), and the PRF (Pseudorandom Function). The cipher suites are described in RFC 5288 and RFC 5289.

The figure below depicts part of a PCAP with a TLS client that is presenting the set of cipher suites that it is capable of doing to the server.

When a TLS connection is established, a TLS handshake occurs. Within the TLS handshake, a client hello and a server hello message are passed. First, the client sends a list of the cipher suites that it supports, in order of preference. Then the server replies with the cipher suite that it has selected from the client’s list.

The following lists three different TLS cipher suite examples that are using the ECDH (Elliptic Curve Diffie-Hellman) exchange (ECDHE) and ECDSAs (Elliptic Curve Digital Signature Algorithm) for authentication and key exchange, instead of using RSA (as shown in the previous topic).

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_GCM_SHA384

- ECDHE_ECDSA is the authentication and key exchange algorithms. ECDHE_ECDSA is used to determine how the client and server will authenticate and establish the pre-master key during the TLS handshake. In this case, both the client and the server will derive the identical pre-master key using the DH parameters (sent in the additional ServerKeyExchange message). The pre-master key is then used to derive the master key and the session-specific keys. With DH key exchanges, in order for the client to authenticate the server, the server will sign the DH parameters that are contained in ServerKeyExchange message with the server’s private key. The client verifies the signature with the server's public key in the server's certificate. Only if the signature is valid, the client will proceed with the TLS handshake.

- AES_256_GCM is the bulk encryption algorithm.

- GCM (Galois Counter Mode) is a mode of operation for an authenticated symmetric key cryptographic block ciphers that has been widely adopted because of its efficiency and performance. GCM is an authenticated encryption algorithm that is designed to provide both data authenticity and confidentiality.

- SHA-384 is used for the pseudorandom function. Since an authenticated encryption mode (GCM) is used, the messages neither have nor require a message authentication code.

- The pseudorandom function is used to generate the keying materials that are used during the TLS session. - TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_128_CBC_SHA256

- ECDHE_ECDSA is the authentication and key exchange algorithms.

- AES_128_CBC is the bulk encryption algorithm. Unlike AES GCM, AES CBC (Cipher Block Chaining) mode does not provide data authenticity (integrity). Therefore, a message authentication code algorithm is required for data authenticity (integrity).

- SHA-256 is the hashed message authentication code algorithm.

- SHA-256 is also used for the pseudorandom function.

- For TLS 1.2, the default pseudorandom function is SHA-256, unless otherwise stated.

- TLS_ECDHE_ECDSA_WITH_AES_256_CBC_SHA256_P384

- ECDHE_ECDSA is the authentication and key exchange algorithms.

- AES_256_CBC is the bulk encryption algorithm. Unlike AES GCM, AES CBC mode does not provide data authenticity (integrity). Therefore, a message authentication code algorithm is required for data authenticity (integrity).

- SHA-256 is the hashed message authentication code algorithm.

- SHA-384 is specified to be used for the pseudorandom function.

Note: