Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 3: Understanding Common TCP/IP Attacks

3.2 Legacy TCP/IP Vulnerabilities

3.3 IP Vulnerabilities

3.4 ICMP Vulnerabilities

3.5 TCP Vulnerabilities

3.6 UDP Vulnerabilities

3.7 Attack Surface and Attack Vectors

3.8 Reconnaissance Attacks

3.9 Access Attacks

3.10 Man-in-the-Middle Attacks

3.11 Denial of Service and Distributed Denial of Service

3.12 Reflection and Amplification Attacks

3.13 Spoofing Attacks

3.14 DHCP Attacks

Legacy TCP/IP Vulnerabilities

The TCP/IP protocol suite (RFC 793), developed under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Defense, was designed to work in a trusted environment. The model was developed as a flexible, fault-tolerant set of protocols that were robust enough to avoid failure if one or more nodes went down. The focus was on solving the technical challenges of moving information quickly and reliably, not to secure it.

The designers of this original network never envisioned the Internet as it exists today. The problem is that weakness is inherent in the design itself and eradicating them is difficult. Many early TCP/IP protocols are now considered insecure and vulnerable to various attacks, ranging from password sniffing to denial of service. As an example, TCP/IP is shipped with Berkley r-utilities. It is a set of tools featuring remote login (rlogin), remote copying (rcp), and remote command execution (rsh). These commands were developed for password-free access to UNIX machines only. Although the r-utilities tools have some advantages, they should be avoided because they can make access extremely insecure. Also, being inherent in the design means that universal cross-platform vulnerabilities are present in the very infrastructure of the Internet and most other networks, like LANs. The fact that TCP over IP is a low-level protocol means that all the higher-level protocols (for example, HTTP, Telnet, and SMTP) are vulnerable by inheritance (for example, hijacking a Telnet connection).

The 1988 attack by the “Morris worm” was a wake-up call for the Internet’s architects, who had done their original work in an era before smart phones, before cyber cafes, before even the widespread adoption of the personal computer. The Morris worm attack was one of the first computer worms that were distributed via the Internet and it was a precursor to other well-known worm attacks including 1999’s Melissa, 2001’s Code Red, 2003’s Slammer, and the SQL Sapphire/Slammer worm in January 2003. According to its creator, the Morris worm was not written to cause damage, but to gauge the size of the ARPANET. It worked by exploiting known vulnerabilities in common utilities including sendmail, which is email routing software, and finger, a tool that showed which users were logged on to the network. However, consequence of the code caused it to be more damaging: a computer could be infected multiple times and each additional process would slow the machine down, eventually to the point of being unusable. The Morris worm opened up computer security as a legitimate topic.

Due to reliance on rsh (normally disabled on untrusted networks), fixes to sendmail, finger, the widespread use of network filtering, and improved awareness of the dangers of weak passwords, the Morris Worm type attacks should not succeed on a properly configured system today. But these virus and worm outbreaks have demonstrated that networked computers continue to be vulnerable to new attacks, despite the widespread deployment of antivirus software and firewalls.

The TCP/IP suite has been modified and enhanced over the years. The protocol suite, consisting of four main protocols (IP, TCP, UDP, and ICMP), describes the ways in which devices communicate on TCP/IP networks, ranging from the way individual chunks of data, which are known as packets, are formatted, to the details of how those packets are routed through various networks to their final destinations. As a security analyst, you need an essential understanding of the protocol structures and their vulnerabilities. The following discussion will include the protocol relationships, and packet and datagram structures, providing details of the protocol vulnerabilities that are relevant to packet analysis.

IP Vulnerabilities

The IP is a connectionless protocol that is mainly used to route information across the Internet. The role of IP is to provide best-effort services for the delivery of information to its destination. IP depends on upper-level TCP/IP suite layers to provide accountability and reliability. Layers above IP use the source address in an incoming packet to identify the sender. To communicate with the sender, the receiving station sends a reply by using the source address in the datagram. Because IP makes no effort to validate whether the source address in the packet that is generated by a node is actually the source address of the node, you can spoof the source address and the receiver will think the packet is coming from that spoofed address.

Many programs for generating spoofed IP datagrams are available for free on the Internet, for example, hping lets you prepare spoofed IP datagrams with a simple one-line command, and you can send them to almost anybody in the world. You can also spoof at various other layers, for example, using ARP spoofing to link a MAC address to the IP address of a legitimate host on the network to divert the traffic that is intended for one station to someone else. The SMTP is also a target for spoofing the email source because SMTP does not verify the sender’s address, so you can send any email to anybody pretending to be someone else. As a result, no packet can be trusted, and each packet must earn its trust through the network’s ability to classify and enforce policy.

The following are some key IP address-based vulnerabilities that threaten network infrastructures:

- Man-in-the-middle attack: An MITM attack intercepts a communication between two systems. Essentially, the attacker inserts a device into a network that grabs packets that are streaming past. Those packets are then modified and placed back on the network for forwarding to their original destination. An MITM attack can completely defeat sophisticated authentication mechanisms because the attacker waits until after a communication session is established, which means that authentication has been completed, before starting to intercept packets. An MITM attack does not directly threaten your network's stability, but it is an exploit that can target a specific destination IP address. A form of MITM is called "eavesdropping." Eavesdropping differs only in that the perpetrator just copies IP packets off the network without modifying them in any way.

- Session hijacking: Session hijacking is a twist on the MITM attack. The attacker gains physical access to the network, initiates an MITM attack and then hijacks that session. In this manner, an attacker can illicitly gain full access to a destination computer by assuming the identity of a legitimate user. The legitimate user sees the login as successful but then is cut off. Subsequent attempts to log back in might be met with an error message that indicates that the user ID is already in use.

- IP address spoofing: Attackers spoof the source IP address in an IP packet. IP spoofing can be used for several purposes. In some scenarios, an attacker might want to inspect the response from the target victim (nonblind spoofing); in other cases the attacker might not care (blind spoofing). Blind IP address spoofing is most frequently used in DoS attacks. Some reasons for nonblind spoofing include sequence-number prediction, hijacking an authorized session, and determining the state of a firewall.

- DoS attack: In a DoS attack, an attacker attempts to prevent legitimate users from accessing information or services. Since the second half of 2010, DoS has been one of the most common attacks in the United States. By targeting your computer and its network connection, or the computers and network of the sites that you are trying to use, an attacker may be able to prevent you from accessing email, websites, online accounts, or other services that rely on the affected computers. Common types of DoS attacks include packet floods and service buffer overflow attacks. Other types of DoS attacks rely on specific flaws in various applications and operating systems, such as the "teardrop" attack which can crash older operating systems. For example, in a teardrop attack, the attacker sends IP fragmented packets to a target machine. Since the machine receiving such packets cannot reassemble them due to a bug in TCP/IP fragmentation reassembly, the packets overlap one another, crashing the target network device.

- DDoS attack: A DDos attack is a DoS attack that features a simultaneous, coordinated attack from multiple source machines. The best-known example of a DDoS attack is the "smurf" attack. Attackers have been known to use four programs to launch DDoS attacks: Trinoo, TFN, TFN2K, and Stacheldraht.

- Smurf attack: A smurf attack exploits the IP broadcast addressing to create a DoS. This attack uses the ICMP. One of the utilities that are embedded in ICMP is ping which is commonly used to test the availability of certain destinations. The attacker installs smurf on a hacked computer. The hacked machine starts continuously pinging one or more networks—with all their attached hosts—using IP broadcast addresses. Every host that receives the broadcast ping message is obliged to respond with its availability. The result is that the hacked machine gets overwhelmed with inbound ping responses.

- Resource exhaustion attacks: Resource exhaustion attacks are forms of DoS attacks. These attacks cause the server’s or network's resources to be consumed to the point where the service is no longer responding, or the response is significantly reduced. By targeting IP routers, an attacker may adversely affect the integrity and availability of the network infrastructure, including end-to-end IP connectivity. Router resources that are commonly affected by packet flood attacks include the following: CPU, packet memory, route memory, network bandwidth, and vty lines.

ICMP Vulnerabilities

ICMP is a connectionless protocol that does not use any port number and works in the network layer. ICMP was not designed to transfer data in the same way as TCP and UDP. Rather, ICMP was intended to carry diagnostic messages to ensure that links were active and to report error conditions when routes, hosts, and ports are inaccessible. ICMP datagrams are often associated with commands that are used by network administrators, such as ping (ICMP echo request) and traceroute (ICMP TTL expired in transit). Most ICMP traffic is generated by routers, firewalls, and endpoints to detect and diagnose network connection issues. ICMP is used to inform the sender that a problem has occurred while delivering the data. For example, if a host is unable to reach another host on the local network, the sender might receive an ICMP Destination Host Unreachable message. If a network link is down, a router may respond to the sender with an ICMP Destination Network Unreachable message. If traffic is blocked by a firewall, the firewall may respond with an ICMP Host Administratively Prohibited message. Every network device must implement ICMP, but some administrators block ICMP to prevent attackers from gathering information about their internal network.

All types of ICMP traffic are interesting to the security analyst. Either the traffic is user-generated (as in the case of ICMP echo requests) or generated by network devices (as in the case of ICMP Destination Network Unreachable). In the first case, it is beneficial to know when someone, especially inside the network, is generating ICMP traffic to scan the network. Traffic that is generated by network devices indicates network issues and outages.

The following are the security issues of ICMP messages that a security analyst needs to understand:

- Reconnaissance and scanning: ICMP can be used to launch information gathering attacks. Attackers can use different methods within the ICMP to find out live host, network topology, and OS fingerprinting, and determine the state of a firewall.

- ICMP unreachables: ICMP unreachables are commonly used by attackers to perform network reconnaissance. In cyber security, network reconnaissance refers to the act of scanning the target network to gather information about the target. For example, during a protocol or port scan, if an ICMP Protocol Unreachable is received, the attacker will know that protocol is not in use on the target device. If an ICMP Port Unreachable is received, the attacker will know that port is not in use on the target device.

- ICMP mask reply: A feature that malicious insiders or outsiders can use to map your IP network. This feature allows the router to tell a requesting endpoint what the correct subnet mask is for a given network.

- ICMP redirects: A router sends an IP redirect to notify the sender of a better route to the destination. The intended purpose of this feature was for a router to send redirects to the hosts on its directly connected networks. However, an attacker can leverage this feature to send an ICMP redirect message to the victim's host, luring the victim's host into sending all traffic through a router that is owned by the attacker. ICMP redirect attack is an example of an MITM attack, where an attacker will act as the middle man for all communication from the source to the destination.

- ICMP router discovery: IRDP allows hosts to locate routers that can be used as a gateway to reach IP-based devices on other networks. Because IRDP does not have any form of authentication, it is impossible for end hosts to tell whether the information they receive is valid or not. Therefore, an attacker can perform an MITM attack using IRDP. Attackers can also spoof the IRDP messages to add bad route entries into a victim’s routing table, so that the victim’s host will forward the packets to the wrong address, and be unable to reach other networks, resulting in a form of a DoS attack.

- Firewalk: Firewalking is an active reconnaissance technique that employs traceroute-like techniques to analyze IP packet responses to determine the gateway ACL filters and map out the networks. The firewalking technique works by sending out TCP or UDP packets with a TTL that is one greater than the targeted gateway. If the gateway allows the traffic, it will forward the packets to the next hop where they will expire and elicit an ICMP Time Exceeded message. If the gateway host does not allow the traffic, it will likely drop the packets and the attacker will see no response. - ICMP tunneling: An ICMP tunnel, also known as ICMPTX, establishes a covert connection between two remote computers, using ICMP echo requests and reply packets. ICMP tunneling can be used to bypass firewalls rules through obfuscation of the actual traffic inside the ICMP packets. Without proper deep packet inspection or log review, network administrators will not be able to detect this type of tunneling traffic through their network. A common ICMP tunneling program is LOKI that uses ICMP as a tunneling protocol for a covert channel. By using LOKI, an attacker can transmit data secretly by hiding their malicious traffic inside ICMP so that the networking devices cannot detect the transmission.

- ICMP-based OS fingerprinting: OS fingerprinting is the process of learning which operating system is running on a device. ICMP can be used to perform an active OS fingerprint scan. For example, if the ICMP reply contains a TTL value of 128, it is probably a Windows machine, and if the ICMP reply contains a TTL value of 64, it is probably a Linux-based machine.

- Denial of service attacks: DoS attacks that use ICMP include the following:

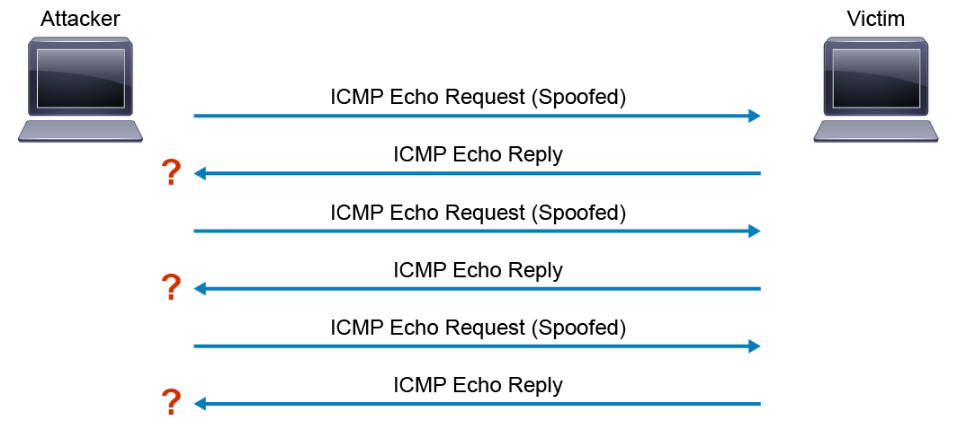

- ICMP flood attack: The attacker overwhelms the targeted resource with ICMP echo request (ping) packets, large ICMP packets, and other ICMP types to significantly saturate and slow down the victim's network infrastructure. The following figure is an example of the ICMP Flood.

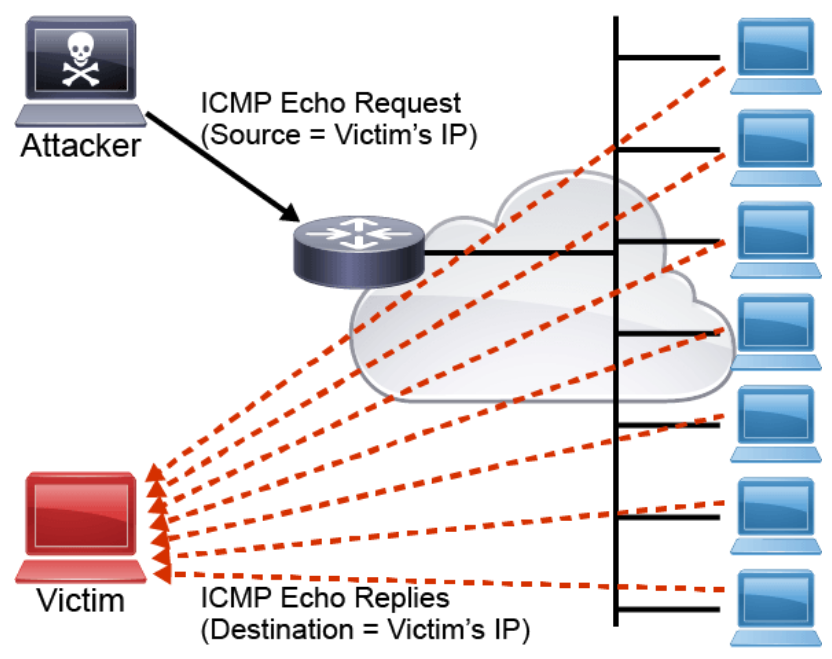

- Smurf attack: In a smurf attack, an attacker broadcasts many ICMP echo request packets using a spoofed source IP address (which is the victim's IP address) to a network using an IP broadcast address. If networking devices do not filter this traffic, then they will be broadcasted to all computers in the network. The victim’s network will get congested with all the ICMP echo replies traffic, which will bring down the productivity of the entire victim's network. This exchange is illustrated in the following figure.

TCP Vulnerabilities

TCP segments reside within IP packets. The TCP header appears immediately after the IP header and supplies information specific to the TCP protocol. TCP provides more functionality than UDP, at the cost of higher overhead, but additional fields in the TCP header help provide reliability, flow control, and stateful communication. Reliable communication is the largest benefit of TCP. TCP incorporates acknowledgments to guarantee delivery instead of relying on upper-layer protocols to detect and resolve errors. If a timely acknowledgment is not received, the sender retransmits the data. But requiring acknowledgments of received data can cause substantial delays. TCP implements flow control to address this issue. Rather than acknowledge one segment at a time, multiple segments can be acknowledged with a single acknowledgment segment.

TCP stateful communication between two parties happens by way of TCP three-way handshake. Before data can be transferred using TCP, a three-way handshake opens the TCP connection. If both sides agree to the TCP connection, data can be sent and received by both parties using TCP. At the conclusion of the TCP session, a four-way handshake generally closes the TCP connection gracefully where a typical tear-down requires a pair of FIN and ACK segments from each TCP endpoint.

Examples of application-layer protocols that make use of TCP reliability are DNS zone transfers, HTTP, SMB, SSL/TLS, FTP, and so on.

Though TCP protocol is a connection-oriented and reliable protocol, there are still vulnerabilities that can be exploited. These vulnerabilities are explained in terms of following attacks:

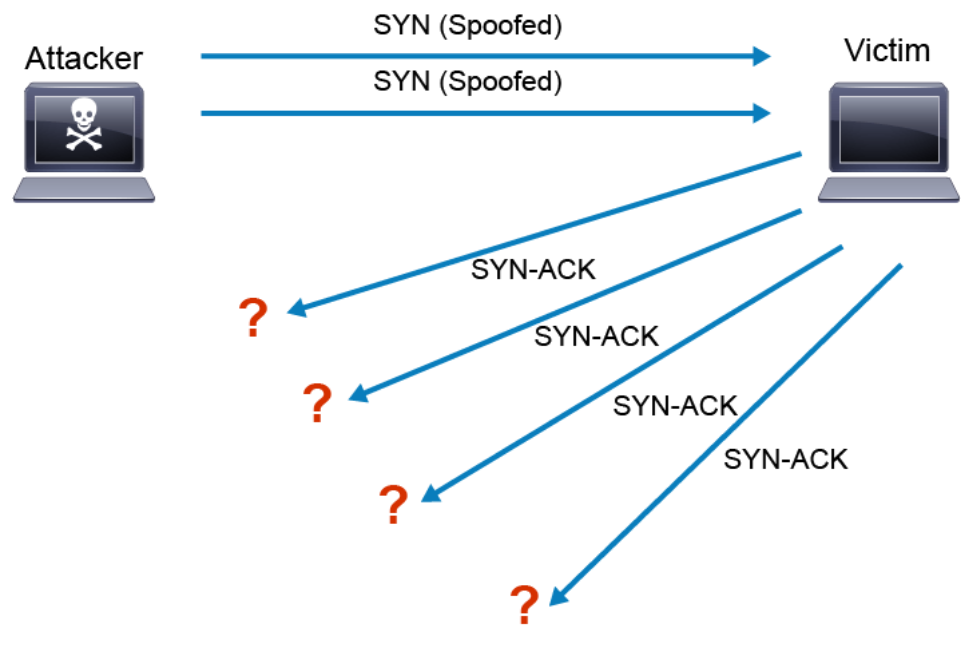

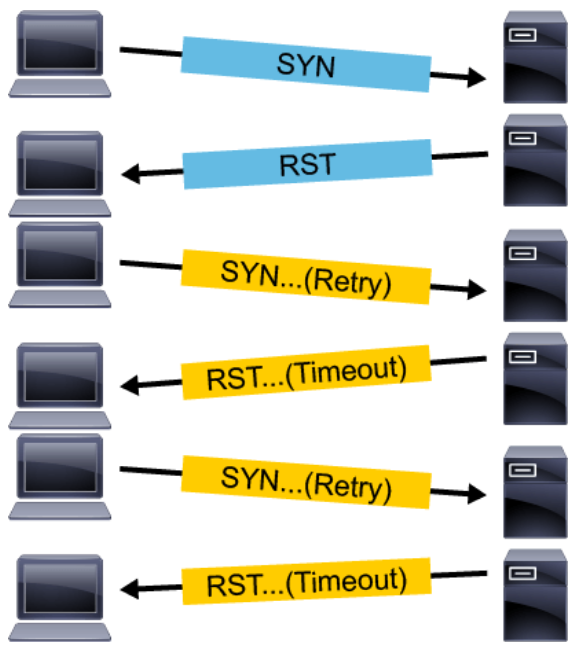

- TCP SYN flooding: TCP SYN flooding causes a DoS attack. It exploits an implementation characteristic of the TCP that can be used to make server processes incapable of responding to any legitimate client's requests. Any service, such as server applications for email, web, and file storage, that binds to and listens on a TCP socket, is potentially vulnerable to TCP SYN flooding attacks. The basis of the SYN flooding attack lies in the design of the three-way handshake that begins a TCP connection.

TCP connections that have been initiated but not finished are called half-open connections. A finite-sized data structure in each host is used to store the state of the half-open connections. As shown in the figure below, an attacking host can send an initial SYN packet with a spoofed IP address, and then the victim sends the SYN-ACK packet, and waits for a final ACK to complete the three-way handshake. If the spoofed address does not belong to a host, then this connection stays in the half-open state indefinitely, thus occupying the finite-sized data structure. If there are enough half-open connections to fill up the entire finite-sized data structure, then the host cannot accept further TCP connection requests, thus denying service to the legitimate TCP connections.

Setting a time limit for half-open connections, then deleting them after the timeout, can help with the TCP SYN flooding problem, but the attacker may continuously send the TCP SYN flood attack traffic. The attacked host will not have space to accept new incoming legitimate TCP connections, but the TCP connection that was established before the attack will have no effect. In this type of attack, the attacker has no interest in examining the responses from the victim. When the spoofed address does belong to a connected host, that host sends a reset to indicate the end of the handshake.

The following are some variations of the TCP SYN flooding attack methods:

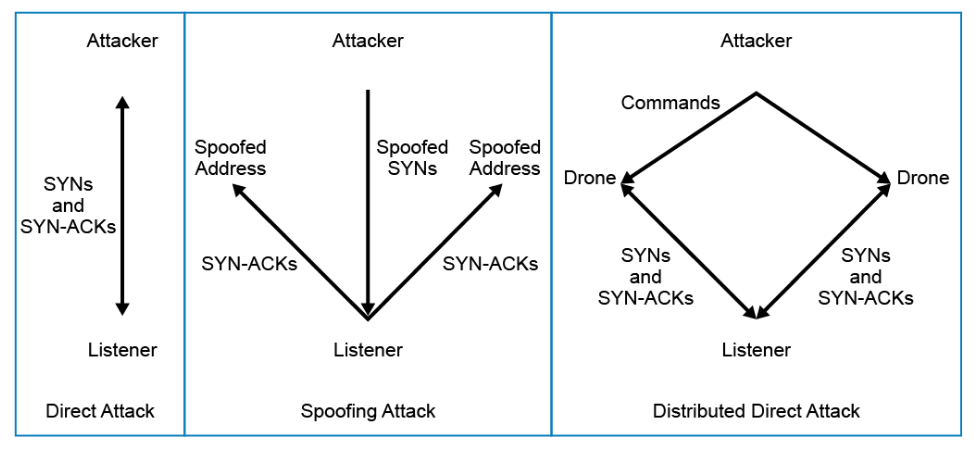

- Direct attack: When attackers rapidly send SYN segments without spoofing their IP source address, that is a direct attack. This method of attack is very easy to perform because it does not involve directly injecting or spoofing packets below the user level of the attacker's operating system. It can be performed by simply using many TCP connect() calls. To be effective, attackers must prevent their operating system from responding to the SYN-ACKs in any way, because any ACKs, RSTs, or ICMP messages will allow the listener to move the TCP out of SYN-RECEIVED. This scenario can be accomplished through firewall rules that either filter outgoing packets to the listener (allowing only SYNs out), or filter incoming packets so that any SYN-ACKs are discarded before they reach the local TCP processing code. When detected, this type of attack is very easy to defend against—a simple firewall rule to block packets with the attacker's source IP address is all that is needed. This defense behavior can be automated, and such functions are available in off-the-shelf reactive firewalls.

- Spoofing-based attack: Another form of SYN flooding attacks uses IP address spoofing, which might be considered more complex than the method used in a direct attack. Instead of merely manipulating local firewall rules, the attacker also needs to be able to form and inject raw IP packets with valid IP and TCP headers. Popular libraries exist to aid with raw packet formation and injection, therefore attacks that are based on spoofing are actually fairly easy. For spoofing attacks, a primary consideration is address selection. If the attack is to succeed, the machines at the spoofed source addresses must not respond in any way to the SYN-ACKs that are sent to them. A very simple attacker might spoof only a single source address that it knows will not respond to the SYN-ACKs, either because no machine physically exists at the address presently, or because of some other property of the address or network configuration. Another option is to spoof many different source addresses, assuming that some percentage of the spoofed addresses will be unrespondent to the SYN-ACKs. This option is accomplished either by cycling through a list of source addresses that are known to be desirable for the purpose, or by generating addresses inside a subnet with similar properties.

- Distributed attacks: The real limitation of single-attacker spoofing-based attacks is that if the packets can somehow be traced back to their true source, the attacker can be easily shut down. Although the tracing process typically involves some time and coordination between ISPs, it is not impossible. A distributed version of the SYN flooding attack, in which the attacker takes advantage of numerous drone machines throughout the Internet, is much more difficult to stop. The example that is shown in figure above, the drones use direct attacks. But to increase the effectiveness even further, each drone could use a spoofing attack and multiple spoofed addresses. Currently, distributed attacks are feasible because there are several "botnets" or "drone armies" of thousands of compromised machines that are used by criminals for DoS attacks. Drone machines are constantly added or removed from the armies and can change their IP addresses or connectivity, so it is quite challenging to block these attacks.

- TCP session hijacking: TCP hijacking is the oldest type of session hijacking. Session hijacking is the attempt to overtake an already active session between two hosts. TCP session hijacking is different from IP spoofing, in which you spoof an IP address or MAC address of another host. With IP spoofing, you still need to authenticate to the target. With TCP session hijacking, the attacker takes over an already-authenticated host as it communicates with the target. The attacker will probably spoof the IP address or MAC address of the host, but session hijacking involves more than address spoofing.

As discussed earlier, sequence numbers are exchanged during a TCP three-way handshake, as follows:

- Host A sends a SYN bit set packet with a sequence number to Host B to establish a TCP session. The sequence number is used to assure the transmission of packets in a chronological order. It is increased by one with each packet. Both sides of the connection wait for a packet with a specified sequence number. The first seq-number for both directions is random.

- Host B will reply with a packet that has the SYN and ACK bits set and contains an initial sequence number. The packet also contains an acknowledgment number, which is the seq-number of the client + 1.

- Host A will reply with an ACK bit set packet to Host B with ISN (Initial Sequence Number) + 1.

If attackers manage to predict the ISN, they can actually send the last ACK data packet to the server, spoofing as the original host, and then hijack the TCP connection. Systems with poor TCP ISN generation are vulnerable to blind TCP spoofing attacks. Attackers can make a full connection to those systems and send, but not receive, data while spoofing a different IP address. The target's logs will show the spoofed IP address, and the attacker can take advantage of any trust relationship between the server and the client. This attack was popular in the mid-90's when people commonly used rlogin, which is an rsh (similar to SSH) that allows users to log in on another host via the network, communicating using TCP port number 513. While the rlogin family is mostly a thing of the past, other types of session hijacking are still actively being used. Session hijacking can also be done at the application level. At the application level, a hijacker can hijack already existing sessions but can also create new sessions from the stolen data, for example, HTTP session hijacking. Hijacking an HTTP session involves obtaining the session ID of the HTTP session, which is the unique identifier of the HTTP session. One way for the attacker to obtain the session ID is by sniffing the HTTP packets. Tools that can be used to perform session hijacking attacks include Juggernaut, Hunt, TTY Watcher, and T-Sight.

Hijacking a TCP session requires an attacker to send a packet with a right seq-number, otherwise they are dropped. The attacker has two options to get the right seq-number:

- Non-blind spoofing: The attacker can see the traffic that is being sent between the host and the target. Non-blind spoofing is the easiest type of session hijacking to perform, but it requires attacker to capture packets as they are passing between the two machines. Spoofing-based attacks were discussed earlier in TCP SYN flooding attack methods.

- Blind spoofing: The attacker cannot see the traffic that is being sent between the host and the target. Blind spoofing is the most difficult type of session hijacking because it is nearly impossible to correctly guess TCP sequence numbers. TCP sequence prediction is a type of blind hijacking because an attacker needs to make an educated guess on the sequence numbers between the host and target. In TCP-based applications, sequence numbers inform the receiving machine which order to put the packets in if they are received out of order. Sequence numbers are a 32-bit field in the TCP header. Therefore, they range from 1 to 4,294,967,295. Every byte is sequenced, but only the sequence number of the first byte in the segment is put in the TCP header. To effectively hijack a TCP session, you must accurately predict the sequence numbers that are being used between the target and host.

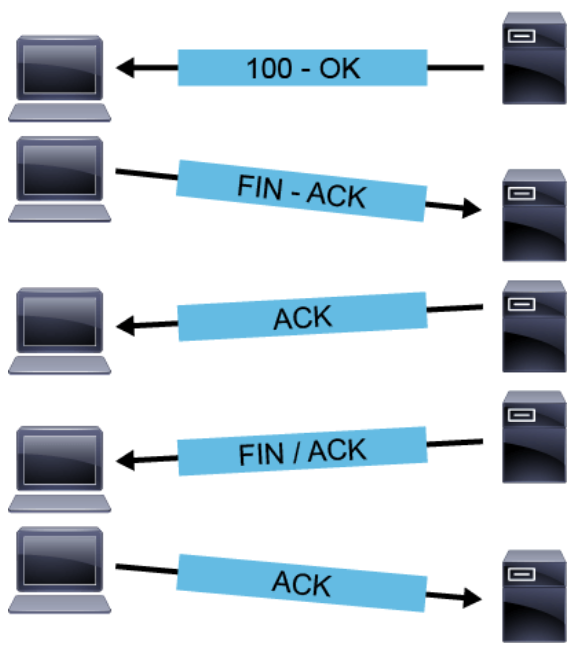

- TCP reset attack: The TCP reset attack, also known as "forged TCP reset" or "spoofed TCP reset packet," is a technique of maliciously killing TCP communications between two hosts. A TCP connection is terminated by using the FIN bit in the TCP flags or by using the RST bit. The regular way that a TCP connection is torn down is by using the FIN bit in the TCP flags. One side of the connection sends a packet with the FIN bit set. The other side of the connection responds with two packets, an ACK, and a FIN of its own. This last FIN is acknowledged by the original station, indicating that the connection has been closed on both sides, as shown in the figure below.

Closing a connection can also be done by using the RST bit in the TCP flags field. In most packets, the RST bit is set to 0 and has no effect. If the RST bit is set to 1, it indicates to the receiving computer that the computer should immediately stop using the TCP connection. A reset indicates that this connection is considered closed, and there is no need to send additional packets. A reset is an abrupt way to tear down the TCP connection. Resets are commonly seen when TCP data packets are sent to a server where no connection has been established, or when SYNs are sent to a port that the server is not listening on. The server should reply with a reset, showing that the connection is closed or unavailable, as shown in the figure below.

Resets can also be sent by applications when a user is suddenly kicked out of an application. When the RST bit is used as designed, it can be a useful tool. But it is possible for an attacker to monitor the TCP packets on the connection and then send a spoofed packet containing a TCP reset to one or both endpoints. The headers in the spoofed packet must indicate, falsely, that the RST packet came from the victim host and not from the attacker. Every field in the IP and TCP headers must be set to a convincing spoofed value for the fake RST packet to trick the victim host into closing the TCP connection. Properly formatted spoofed TCP resets can be a very effective way to disrupt any TCP connection that the attacker can monitor.

UDP Vulnerabilities

UDP is a connectionless transport-layer protocol that provides an interface between IP and upper-layer processes. UDP protocol ports distinguish multiple applications running on a single device from one another. Unlike the TCP, UDP adds no reliability, flow-control, or error-recovery functions to IP. Because of UDP’s simplicity, UDP headers contain fewer bytes and consume less network overhead than TCP. The UDP segment’s header contains only source and destination port numbers, a UDP checksum, and the segment length. UDP is useful in situations where the reliability mechanisms of TCP are not necessary, such when a higher-layer protocol might provide error and flow control. UDP is the transport protocol for several well-known application-layer protocols, including NFS, SNMP, DNS, TFTP, and real-time services, such as online games, streaming media, and VoIP.

UDP is vulnerable because the checksum, which is an optional field that is used to detect transmission errors, is easy to recompute for attackers who want to alter application data. UDP has no algorithm for verifying the sending packet source. An attacker can eavesdrop on UDP packets and make up false UDP packets, pretending that the UDP packet is sent from another source (spoofing). The receiver of the packet has no guarantee that the source IP address in the receiving packet is the real source of the packet. For example, SNMPv1 and DNS messages use UDP as transport protocol, and are vulnerable to eavesdropping. It is easy for an attacker to eavesdrop on and make up false messages using UDP, as long as the attacker knows the format of the messages that are sent and that the messages are not encrypted.

Most attacks involving UDP relate to exhaustion of some shared resource (buffers, link capacity, and so on), or exploitation of bugs in protocol implementations, causing system crashes or other insecure behavior. Both fall into the broad category of DoS attacks. For example, in UDP flood attacks, similar to TCP flood attacks, the main goal of the attacker is to cause system resource starvation. A UDP flood attack is triggered by sending many UDP packets to random ports on the victim’s system. The victim’s system will notice that no application is listening on that port and reply with an ICMP destination port unreachable packet. If many UDP packets are sent, the victim will be forced to send numerous ICMP destination port unreachable packets. Usually, these attacks are accomplished by spoofing the attacker’s source IP address. Software, such as Low Orbit Ion Cannon and UDP Unicorn, can be used to perform UDP flooding attacks.

The SQL Slammer worm attack of 2003 is a classic example of a software security vulnerability involving UDP port 1434. Microsoft SQL Server 2000 contains three vulnerabilities that can allow a remote attacker to execute arbitrary code or crash the server. The vulnerabilities lie in the SQL Server 2000 Resolution Service. SQL Server 2000 allows several instances of the SQL server to be used on a single machine. Because multiple instances cannot use the standard SQL server session port, TCP port 1433, other instances listen on assigned ports. The SQL Server Resolution Service, which operates on UDP port 1434, responds to the clients’ query, so the clients can connect to the appropriate SQL server instance. Two buffer overflow vulnerabilities can be exploited by sending a specially malformed packet to the SQL Server Resolution Service on UDP port 1434 to cause the heap or the stack memory to be overwritten. If remote attackers successfully exploit the vulnerabilities, they can execute arbitrary code on the system. An unsuccessful attempt is likely to crash the SQL server service. The arbitrary code would be executed in the security context of the SQL server and may be able to perform any database function. Exploit code for the discussed vulnerabilities is publicly available.

A DoS vulnerability can also be exploited through the SQL keep-alive mechanism over UDP port 1434. The SQL server system uses a keep-alive mechanism to determine which instances are active and which are inactive. When an instance receives a keep-alive packet with the value of 0x0A on UDP port 1434, it generates and returns to the sender a keep-alive packet with the same 0x0A value. If the first keep-alive packet has been spoofed to appear to come from another SQL server system’s UDP port 1434, both servers will continually send packets with the value of 0x0A to each other, generating a packet storm that continues until one of the servers is brought offline or rebooted.A DoS vulnerability can also be exploited through the SQL keep-alive mechanism over UDP port 1434. The SQL server system uses a keep-alive mechanism to determine which instances are active and which are inactive. When an instance receives a keep-alive packet with the value of 0x0A on UDP port 1434, it generates and returns to the sender a keep-alive packet with the same 0x0A value. If the first keep-alive packet has been spoofed to appear to come from another SQL server system’s UDP port 1434, both servers will continually send packets with the value of 0x0A to each other, generating a packet storm that continues until one of the servers is brought offline or rebooted.

Attack Surface and Attack Vectors

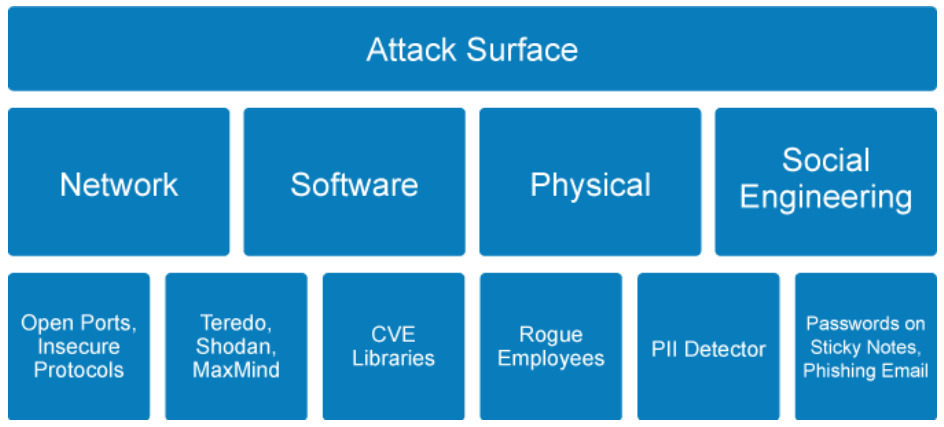

Attack surface is the total sum of all the vulnerabilities in a given computing device or network that are accessible to the attackers. Attack surface may be categorized into different areas, such as software attack surfaces (open ports on a server), physical attack surfaces (USB ports on a laptop), network attack surfaces (console ports on a router), and human/social engineering attack surfaces (employees with access to sensitive information).

Attack vectors are the paths or means by which the attackers gain access to a resource (such as end-user hosts or servers) in order to deliver malicious software or malicious outcome. Attack vectors enable the attackers to exploit system vulnerabilities. Many attack vectors take advantage of the human element in the system, because that is often the weakest link. For example, if the attack vector is a malicious file, then the victim needs to be tricked into opening it for the attack to work.

A smaller attack surface can help make the organization less exploitable, reducing the risk. A greater attack surface makes the organization more vulnerable to attacks, which increases the risk.

Attack surfaces can be divided in to the following four categories:

- The network attack surface comprises all vulnerabilities that are related to ports, protocols, channels, devices (smart phones, laptops, routers, and firewalls), services, network applications (SaaS), and even firmware interfaces. For example, some network protocols are inherently more insecure than others as they pass data over the network unencrypted. These protocols include Telnet, FTP, HTTP, and SMTP. Many network file systems, such as NFS and SMB, pass information over the network unencrypted. Remote memory dump services, like netdump, also pass the contents of memory over the network unencrypted. Memory dumps can contain passwords or, even worse, database entries and other sensitive information. Other services, such as

fingerandrwhod, reveal information about users of the system. Network printers are also the target of a wide array of attacks from hackers because the operating system driver, management tools, and the printer’s software make them vulnerable. Printers can be attacked via the web-based administrative interface, SMTP, FTP, and SNMP. - The software attack surface is the complete profile of all functions in any code that is running in a given system that is available to an unauthenticated user. An attacker or a piece of malware can use various exploits to gain access and run code on the target machine. The software attack surface is calculated across many different kinds of code, including applications, email services, configurations, compliance policy, databases, executables, DLLs, web pages, mobile apps, device OS, and so on. Unpatched software, such as Java, Adobe Reader, and Adobe Flash, also provide greater software attack surface because they are widely used. Publicly known cybersecurity vulnerabilities are listed in CVE libraries. Common CVE identifiers make it easier to share data across separate network security databases and tools, and provide a baseline for evaluating the coverage of an organization’s security tools.

- The physical attack surface is composed of the security vulnerabilities in a given system that are available to an attacker in the same location as the target. The physical attack surface is exploitable through inside threats such as rogue employees, social engineering ploys, and intruders who are posing as service workers. External threats include password retrieval from carelessly discarded hardware, passwords on sticky notes, and physical break-ins. Also, consider a scenario where an intruder steals or downloads the information from an entire drive and extracts the target data in the future.

Note: While the network and software attack surface categories are generally agreed upon within the IT industry, the other categories are more loosely defined. For example, you may see overlap between the physical and social engineering categories or references to social engineering as an attack vector within the physical attack surface. - The social engineering attack surface usually takes advantage of human psychology: the desire for something free, the susceptibility to distraction, or the desire to be liked or to be helpful. A few examples of human social engineering attacks are fake calls to IT, where the attacker is posing as an employee to get a password; or media drops where an employee might find a flash drive in the parking lot, and when they use that device, they inadvertently execute automatic running code leading to a data breach. Socially engineered Trojans provide another method of attack. An end user browses to a website that is usually trusted, which prompts the end user to run a Trojan. Most of the time the website is a legitimate, innocent victim that has been temporarily compromised by hackers. Another very popular method is an APT attacker sends a very specific phishing campaign, which is known as spear-phishing, to multiple employees' email addresses. The phishing email contains a Trojan attachment, which at least one employee is tricked into running. After the initial execution and first computer takeover, an APT (advanced persistent threat) attacker can compromise an entire enterprise in a short time.

An attack vector is a path or route by which an attack was carried out. Examples of attack vectors include malware that is delivered to users who are legitimately browsing mainstream websites, spam emails that appear to be sent by well-known companies but contain links to malicious sites, third-party mobile applications that are laced with malware that are downloaded from popular online marketplaces, and insiders using information access privileges to steal intellectual property from employers.

Common security threats include the following:

- Reconnaissance: The attacker attempts to gather information about targeted computers or networks that can be used as a preliminary step toward a further attack seeking to exploit the target system. For example, what operating system is on the target systems? Is there a firewall? Which ports are available? What CMS does the system run? There are also sources of information such as Facebook, Twitter, and Google that can be used to gather information about organizations or persons that are being targeted.

- Known vulnerabilities: The attacker finds weakness in hardware and software and then exploits those vulnerabilities. There are several online resources that publish information about vulnerabilities that have been discovered in different systems. Often, a proof-of-concept attack code will be provided with the vulnerability disclosure. Each platform has its own strengths and weakness. Once the target system is identified, it is simply a matter of trying out the different attacks for the targeted system to see if any of them work.

- SQL injection: This attack works by manipulating the SQL database queries that the web application sends. An application can be vulnerable if it does not sanitize user input properly, or uses untrusted parameter values in database queries without validation.

- Phishing: The attacker sends out spam email to thousands of recipients. The email contains a link to a malicious site that has been set up to look like, for instance, a regular bank’s site. When the user enters their credentials in the login form, it actually is captured by the malicious site and then used to impersonate that user on the real site. Spear phishing is another variation of the phishing attack, in which the attacker usually targets specific persons. The RSA breach in 2011, which resulted in unspecified data that are related to their SecurID product being stolen, started with a spear phishing attack.

- Malware: Short for “malicious software,” malware may be computer viruses, worms, Trojan horses, dishonest spyware, and malicious rootkits.

- Weak authentication: These attacks exploit poorly designed and/or implemented authentication mechanisms. Weak authentication usually means one or more of the following: weak, guessable passwords are allowed, no lockout enforcement after a specific number of invalid login attempts, or the password reset methods are not secure.

Other common threats, such as security misconfiguration, cross-site scripting, cross-site request forgery, and HTTP header manipulation, have not been included in the list above.

Reconnaissance Attacks

A reconnaissance attack is an attempt to learn more about the intended victim before attempting a more intrusive attack, such as an actual access or DoS. The goal of reconnaissance is to discover the following information about targeted computers or networks:

- IP addresses, sub-domains, and related information on a target network

- Accessible UDP and TCP ports on target systems

- The operating system on target systems

There are four main subcategories or methods for gathering network data:

- Packet sniffers: Packet sniffing, or packet analysis, is the process of capturing any data that are passed over the local network and looking for any information that may be useful to an attacker. The packet sniffer may be either a software program or a piece of hardware with software installed in it that captures traffic that is sent over the network, which is then decoded and analyzed by the sniffer. Tools, such as Wireshark, Ettercap, or NetworkMiner, give anyone the ability to sniff network traffic with a little practice or training.

- Ping sweeps: A ping sweep is another kind of network probe. In a ping sweep, the attacker sends a set of ICMP echo packets to a network of machines, usually specified as a range of IP addresses, and sees which ones respond. The idea is to determine which machines are alive and which aren't. Once the attacker knows which machines are alive, he can focus on which machines to attack and work from there. The fping command is one of the many tools that can be used to conduct ping sweeps.

- Port scans: A port scanner is a software program that surveys a host network for open ports. As ports are associated with applications, the attacker can use the port and application information to determine a way to attack the network. The attacker can then plan an attack on any vulnerable service that they find. Examples of insecure services, protocols, or ports include but are not limited to port 21 (FTP), port 23 (Telnet), port 110 (POP3), 143 (IMAP), and port 161 (SNMPv1 and SNMPv2) because protocols using these ports do not provide authenticity, integrity, and confidentiality. NMAP is one of the many tools that can be used for conducting port scans.

- Information queries: Information queries can be sent via the Internet to resolve hostnames from IP addresses or vice versa. One of the most commonly used queries is the nslookup command. You can use nslookup by opening a Windows or Linux command prompt window on your computer and entering the nslookup command, followed by the IP address or hostname that you are attempting to resolve.

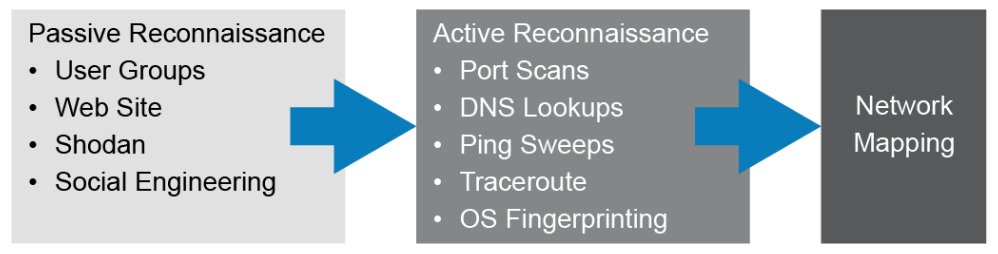

Passive and Active Reconnaissance

Initially, an attacker attempts to gain information about targeted computers or networks that can be used as a preliminary step toward a further attack seeking to exploit the target system. A reconnaissance attack can be active or passive.

whois

Attackers passively start using standard networking command-line tools such as dig, nslookup, and whois to gather public information about a target network from DNS registries. The nslookup and whois tools are available on both Windows, UNIX, and Linux platforms, and dig (domain information groper) is available on UNIX and Linux systems.

Shodan Search Engine

Another innocuous tool is the Shodan search engine with metadata filter capabilities that can help an attacker identify a specific device, such as a computer, router, and server. For example, an attacker can search for a specific system, such as a Cisco 3945 router, running a certain version of the software, and then explore further vulnerabilities.

Robots.txt File

The Robots.txt file is another example where attacker can gather a lot of valuable information from a target’s website. The Robots.txt file is publicly available and found on websites that gives instructions to web robots (also known as search engine spiders), about what is and is not visible using the robots exclusion protocol. An attacker can find the Robots.txt file in the root directory of a target website.

After the passive reconnaissances, the attacker can start using active reconnaissance tools such as ping sweeps, traceroutes, port scans, or operating system fingerprinting to actually send packets to discover the target systems. One of the tools that can be used is traceroute to find out the IP addresses of routers and firewalls that protect victim hosts. Ping sweeps of the addresses can present a picture of the live hosts in a particular environment. After a list of live hosts is generated, the attacker can probe further by running port scans on the live hosts. The attacker can use this information to determine the easiest way to exploit a vulnerability.

NMAP Port Scan

Port scanning tools like Network Mapper can cycle through all well-known ports to provide a complete list of all services that are running on the hosts. Nmap is an open-source tool that is specialized in network exploration and security auditing. Design and operation of port scans uses two components: a host address and a port number that is used by host services. An attacker can attempt to connect to a device on a specified array of ports, such as 21 (FTP), 23 (Telnet) and 25 (SMTP). With the information received from these scans, an attacker can find open ports that could allow access to a network and launch more sophisticated attacks.

Note:

NMAP supports a range of scanning options. The SYN scan (-sS option) is the default and most popular scan option. It can be performed quickly, scanning thousands of ports per second on a fast network not hampered by restrictive firewalls. It is also relatively unobtrusive and stealthy since it never completes TCP connections. For more information, refer to https://nmap.org.

Vulnerability Scanners

An authorized security administrator can use vulnerability scanners, such as Nessus and OpenVAS, to locate vulnerabilities in their own networks and patch them before they can be exploited. Of course, these tools can also be used by attackers to locate vulnerabilities before an organization even knows that they exist. After getting a foothold in a network, an attacker can use these same tools to pivot sideways and scan machines on the network to extend their positions.

Note:

Use of vulnerability scanners by unauthorized personnel is usually a violation of governing security policies. Do not experiment with vulnerability scanners on networks unless you are explicitly authorized to do so.

Access Attacks

An access attack is an attempt to access another user account or network device through improper, unauthorized means. Access attacks exploit known vulnerabilities in authentication services, FTP services, and web services to gain entry to web accounts, confidential databases, and other sensitive information. After gaining access to your network with a valid account, an attacker can obtain lists of valid user and computer names and network information, modify server and network configurations, including access controls and routing tables, and modify, reroute, or delete your data.

There are many attacks which can lead to a system being compromised, and allowing the attacker to gain unauthorized access to the system. The following are some prominent types of attacks:

- Password attack is typically used to obtain system access. When access is obtained, the attacker is able to read, modify, or delete data, and add, modify, or remove network resources. For example, tools like "John the ripper," and "Cain and Abel" are password cracker tools.

- Spoofing/masquerading attack is a situation in which one person or program successfully masquerades as another by falsifying data and gaining illegitimate access.

- Session hijacking is an attack in which the session established by the client to the server is taken over by a malicious person or process.

- Malware is used to infect the victim's system with malicious software.

Man-in-the-Middle Attacks

MITM attacks, sometimes referred to as eavesdropping attacks or connection hijacking attacks, exploit inherent vulnerabilities of TCP/IP protocol at various layers. The attack is a derivative of packet sniffing and spoofing techniques and if carried out properly, it can be completely invisible to the victims, making it difficult to detect and stop. Generally, in MITM attacks, a system that has the ability to view the communication between two systems imposes itself in the communication path between those other systems. The main objective is to steal the information being transmitted between two parties. TCP/IP works on a handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK). This three-way handshake establishes a connection between two different network interface cards, which then use packet sequencing and data acknowledgements to send or receive data. The data flows from the physical layer all the way up to the application layer. As a security analyst, it is important to understand that MITM attacks may occur at the different layers.

Examples of OSI layer MITM attacks include the following:

- Physical layer: Tap someone's physical connection, and send all packets to the MITM

- Data link layer: Use ARP poisoning to cause victims to send all their packets to the MITM

- Network layer: Manipulate packet routing to route all the packets to the MITM

- Session layer: The SSL/TLS MITM de-crypts, examines, then re-encrypts the HTTP over SSL/TLS traffic. For this attack to work, the victim's web browser must trust the certificate that is presented by the SSL/TLS MITM which can be caused by first injecting some malware into the victim's web browser.

- Application layer: Man-in-the-browser attack. Like most attacks, man-in-the-browser begins with a malware infection. The malware injects itself into the victim's web browser, and waits in stealth mode until the user visits a specific web site. At that point, the malware goes into action, tricking the user into entering sensitive information on the web page. Different types of malware typically have different attack targets hard-coded into its code. For example, Zeus generally targets banking sites. When the malware is activated, it may manipulate the web page being loaded by injecting extra fields into the web page to collect sensitive pieces of information, or act as a keylogger to intercept the data. The idea is that no matter how careful you are about scrutinizing URLs and ensuring that you go to the correct web site, the web browser cannot be trusted because it has been compromised.

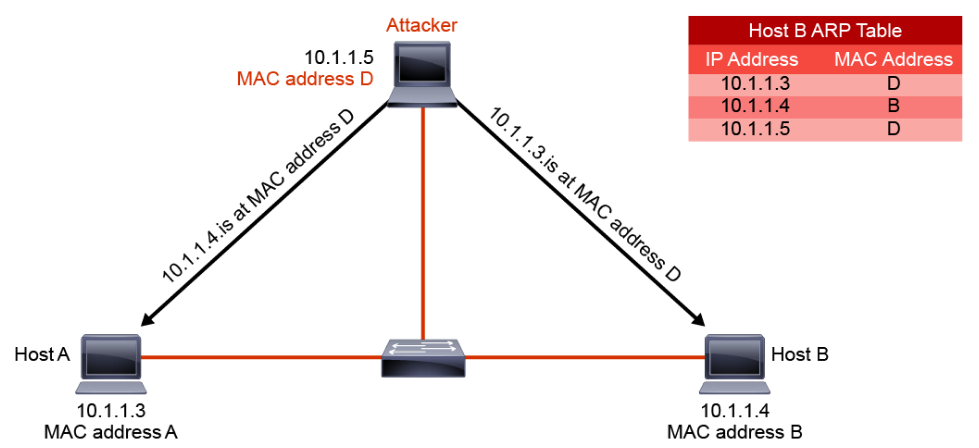

- ARP poisoning: An ARP-based MITM attack is achieved when an attacker poisons the ARP cache of two devices with the MAC address of the attacker's NIC. Once the ARP caches have been successfully poisoned, each victim device sends all its packets to the attacker when communicating to the other device and puts the attacker in the middle of the communications path between the two victim devices. It allows an attacker to easily monitor all communication between victim devices. The intent is to intercept and view the information being passed between the two victim devices and potentially introduce sessions and traffic between the two victim devices.

The figure illustrates an ARP-based MITM attack. The attacker poisons the ARP caches of hosts A and B so that each host will send all its packets to the attacker when communicating to the other host.

A MITM attack can be passive or active. In passive attacks, attackers steal confidential information. In active attacks, attackers modify data in transit or inject data of their own. ARP cache poisoning attacks often target a host and the host’s default gateway. ARP cache poisoning puts the attacker as a MITM between the host and all other systems outside of the local subnet. - ICMP-based MITM attack: An ICMP MITM attack is accomplished by spoofing an ICMP redirect message to any router that is in the path between the victim client and server. An ICMP redirect message is typically used to notify routers of a better route; however, it can be abused to effectively route the victim's traffic through an attacker-controlled router. The threat of this attack is mitigated by routers that have static routes and routers that do not accept/process ICMP redirect packets.

- DNS-based MITM attack: DNS spoofing is an MITM technique that is used to supply false DNS information to a host so that when they attempt to browse, for example, http://www.xyzbank.com at the IP address XXX.XX.XX.XX, the host is actually sent to an imposter https://www.xyzbank.com that is residing at IP address YYY.YY.YY.YY, which an attacker has created in order to steal online banking credentials and account information from unsuspecting users.

- DHCP-based MITM attack: Similar to the DNS attack, DHCP server queries and responses are intercepted. This interception helps the attacker gain complete knowledge of the network, such as host names, MAC addresses, IP addresses, and the DNS servers. This information is further used to plant advanced attacks to steal the information. An attacker can initiate a DoS attack on a real DHCP server to keep it busy, and in the meanwhile spoof and respond to the DHCP host queries by itself.

Note:

Security technologies can often be used either for attack or defense. The discussion above illustrates MITM techniques for attack. Some security products have features which also rely on MITM behavior. For example, the Cisco Web Security Appliance can be deployed as an HTTPS proxy, where it decrypts and re-encrypts SSL protected data so that it can analyze the contained data and provide services to protect against data loss and exfiltration.

Denial of Service and Distributed Denial of Service

DoS attacks attempt to consume all the critical computer or network resources in order to make them unavailable for valid use. DoS attacks are considered a major risk, because they can easily disrupt the operations of a business and they are relatively simple to conduct.

Reflection and Amplification Attacks

A reflection attack is a type of DoS attack in which the attacker sends a flood of protocol request packets to various IP hosts. The attacker spoofs the source IP address of the packets such that each packet has as its source address the IP address of the intended target rather than the IP address of the attacker. The IP hosts that receive these packets become “reflectors.” The reflectors respond by sending response packets to the spoofed address (the target), thus flooding the unsuspecting target.

If the request packets that are sent by the attacker solicit a larger response, the attack is also an amplification attack. In an amplification attack, a small forged packet elicits a large reply from the reflectors. For example, some small DNS queries elicit large replies. Amplification attacks enable an attacker to use a small amount of bandwidth to create a massive attack on a victim by hosts around the Internet.

It is important to note that reflection and amplification are two separate elements of an attack. An attacker can use amplification with a single reflector or multiple reflectors. Reflection and amplification attacks are very hard to trace because the actual source of the attack is hidden.

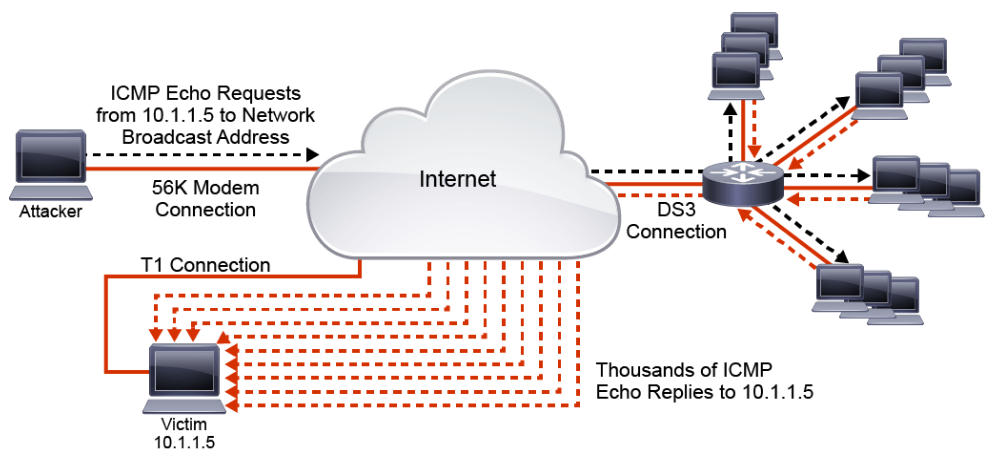

A classic example of reflection and amplification attacks is the smurf attack, which was common during the late 1990s. Although the smurf attack no longer poses much of a threat (because mitigation techniques became standard practice some time ago), it provides a good example of amplification. In a smurf attack, the attacker sends numerous ICMP echo-request packets to the broadcast address of a large network. These packets contain the victim’s address as the source IP address. Every host that belongs to the large network responds by sending ICMP echo-reply packets to the victim. The victim is flooded with unsolicited ICMP echo-reply packets.

The figure below illustrates a smurf attack. Note the differentials in bandwidth of the Internet connections. The attacker has a very small, 56 Kbps dial-up connection. The target has a much larger T1 connection (1.544 Mbps). The reflector network has an even larger DS-3 connection (45 Mbps). The small 56K stream of echo requests with the spoofed source address of victim 10.1.1.5 is sent to the broadcast addresses of the large network. As a result, thousands of echo replies are sent to 10.1.1.5 for each spoofed echo, and the target T1 is fully consumed.

Smurf attacks can easily be mitigated on a Cisco IOS device by using the no ip directed-broadcast interface configuration command, which has been the default setting in Cisco IOS Software since release 12.0. With the no ip directed-broadcast command configured for an interface, broadcasts destined for the subnet to which that interface is attached will be dropped, rather than being broadcast.

Note:

An IP-directed broadcast is an IP packet whose destination address is a valid broadcast address for some IP subnet, but which originates from a node that is not itself part of that destination subnet.

While smurf attacks no longer pose the threat they once did, newer reflection and amplification attacks pose a huge threat. For example, in March 2013, DNS amplification was used to cause a DDoS that made it impossible for anyone to access an organization’s website. This attack was so massive that it also slowed Internet traffic worldwide. The attackers were able to generate up to 300 Gbps of attack traffic by exploiting DNS open recursive resolvers, which will respond to DNS queries from any host. By sending an open resolver a very small, deliberately formed query with the spoofed source address of a target, an attacker can evoke a significantly larger response to the intended target. Attacks such as this use many compromised source systems and multiple DNS open resolvers, so the effects on the target devices are magnified. The Open Resolver Project cataloged 28 million open recursive DNS resolves on the internet in 2013. DNS operations and DNS-based attacks will be discussed in more details in later sections.

In February 2014, an NTP amplification attack generated a new record in attack traffic: over 400 Gbps. NTP has some characteristics that make it an attractive attack vector. Like DNS, NTP uses UDP for transport. Like DNS, some NTP requests can result in replies that are much larger than the request. For example, NTP supports a command that is called monlist, which can be sent to an NTP server for monitoring purposes. The monlist command returns the addresses of up to the last 600 machines with which the NTP server has interacted. If the NTP server is relatively active, this response is much bigger than the request sent, making it ideal for an amplification attack.

Spoofing Attacks

An attack can be considered a spoofing attack any time an attacker injects traffic that appears to be sourced from a system other than the attacker’s system itself. Spoofing is not specifically an attack, but spoofing can be incorporated into various types of attacks.

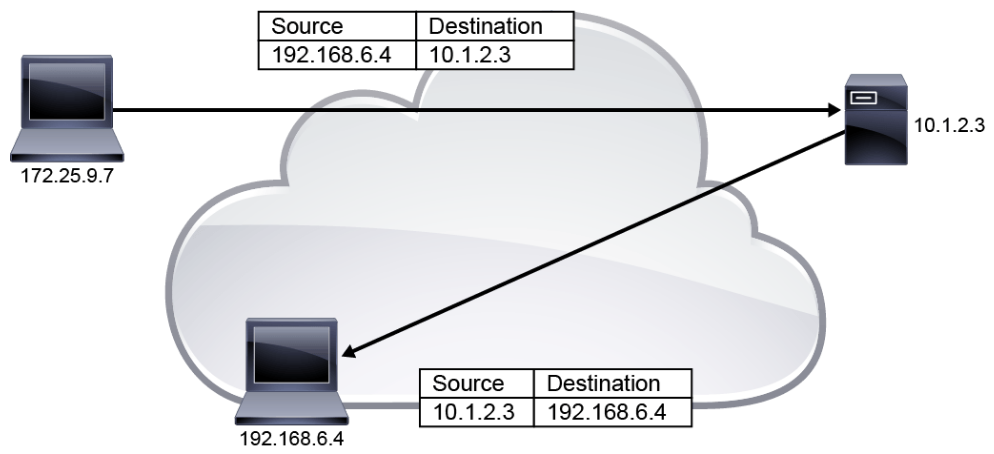

The figure below illustrates IP address spoofing. Attacker 172.25.9.7 sends a packet to server 10.1.2.3 but specifies 192.168.6.4 as the source address of the packet. Server 10.1.2.3 sends its response packet to what it believes to be the originating system, host 192.168.6.4.

There are several types of spoofing, including the following:

- IP address spoofing: IP address spoofing is the most common type of spoofing. To perform IP address spoofing, attackers use source IP addresses that are different than their real IP addresses.

- MAC address spoofing: To perform MAC address spoofing, attackers use MAC addresses that are not their own. MAC address spoofing is generally used to exploit weakness at Layer 2 of the network.

- Application or service spoofing: One example is DHCP spoofing, which can be done with either the DHCP server or the DHCP client. To perform DHCP server spoofing, the attacker enables a rogue DHCP server on a network. When a victim host requests a DHCP configuration, the rogue DHCP server responds before the authentic DHCP server. The victim is assigned an attacker-defined IP configuration. From the client side, an attacker can spoof many DHCP client requests, specifying a unique MAC address per request. The DHCP server's IP address pool may become exhausted, leading to a DoS against valid DHCP client requests. Another simple example of spoofing at the application layer is an email from an attacker which appears to have been sourced from a trusted email account.

Another example of spoofing is a land attack. The attack is named for the name of the file, land.c, used for the original source code that is compiled into an attack tool. In a land attack, the attacker sends a TCP SYN request using the same IP address and port as both the source and destination IP address and port. The IP address and port combination that is used is that of the target system. The target system replies to itself and, if the system is vulnerable, the response leads to a system crash.

DHCP Attacks

In a TCP/IP-based network, every device must have a unique unicast IP address to access the network and its resources. Without DHCP, the IP address for each client (a host that is requesting initialization parameters from a DHCP server) must be configured manually and IP addresses for computers that are removed from the network must be manually reclaimed. With DHCP, the IP address allocation process is automated and managed centrally. The DHCP server maintains a pool of IP addresses and leases an address to any DHCP-enabled client when it starts up on the network. Because the IP addresses are dynamic (leased) rather than static (permanently assigned), addresses that are no longer in use are automatically returned to the pool for reallocation.

DHCP was based on BOOTP when the Internet was relatively small. Not only does DHCP run over IP and UDP, which are inherently insecure, the DHCP protocol itself has no security provisions, which causes a serious vulnerability in networks because DHCP deals with critical configuration information.

Two classes of potential security problems are related to DHCP:

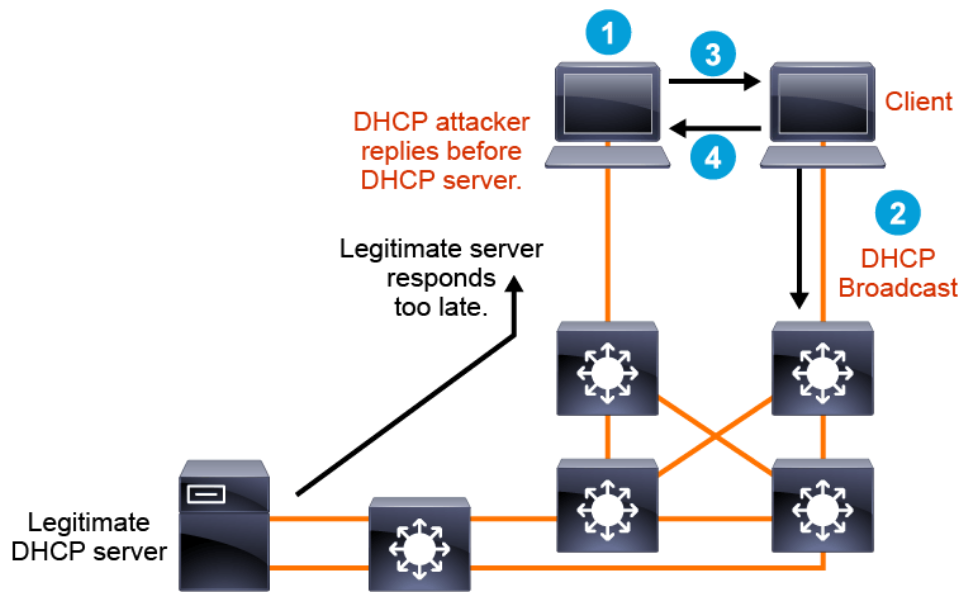

- DHCP server spoofing: The attacker runs DHCP server software and replies to DHCP requests from legitimate clients. As a rogue DHCP server, the attacker can cause a DoS by providing invalid IP information. The attacker can also perform confidentiality or integrity breaches via a man-in-the-middle attack. The attacker can assign itself as the default gateway or DNS server in the DHCP replies, later intercepting IP communications from the configured hosts to the rest of the network.

The following is the DHCP server spoofing attack process:

- An attacker activates a malicious DHCP server on the attacker port

- The client broadcasts a DHCP configuration request.

- The DHCP server of the attacker responds before the legitimate DHCP server can respond, assigning attacker-defined IP configuration information.

- Host packets are redirected to the attacker address because it emulates the default gateway that it provided to the client.

- DHCP starvation: A DHCP starvation attack works by the broadcasting of DHCP requests with spoofed MAC addresses. If enough requests are sent, the network attacker can exhaust the address space available to the DHCP servers in a time period. The network attacker can then set up a rogue DHCP server. However, the exhaustion of all the DHCP addresses is not required to introduce a rogue DHCP server.

Whether an attacker attempts to take a DHCP server offline or provide clients with IP information that forces the client machine to use the wrong gateway or DNS server, attack indicators are available to security analysts. Cisco switch features such as DHCP Snooping and IP source guard can be used to defend against DHCP attacks.